Back Pain in Adolescents With Idiopathic Scoliosis:

Epidemiological Study for 43,630 Pupils

in Niigata City, JapanThis section was compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: European Spine Journal 2011 (Feb); 20 (2): 274–279 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Tsuyoshi Sato, Toru Hirano, Takui Ito, Osamu Morita, Ren Kikuchi,

Naoto Endo, and Naohito Tanabe

Department of Orthopedic Surgery,

Niigata Prefectural Shibata Hospital,

Shibata, Japan.There have been a few studies regarding detail of back pain in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis (IS) as prevalence, location, and severity. The condition of back pain in adolescents with IS was clarified based on a cross-sectional study using a questionnaire survey, targeting a total of 43,630 pupils, including all elementary school pupils from the fourth to sixth grade (21,893 pupils) and all junior high pupils from the first to third year (21,737 pupils) in Niigata City (population of 785,067), Japan.

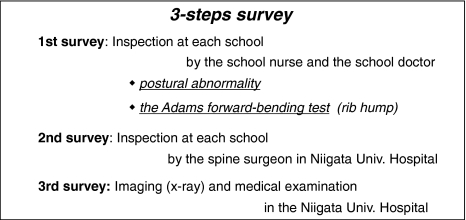

32,134 pupils were determined to have valid responses (valid response rate: 73.7%). In Niigata City, pupils from the fourth grade of elementary school to the third year of junior high school are screened for scoliosis every year. This screening system involves a three-step survey, and the third step of the survey is an imaging and medical examination at the Niigata University Hospital.

In this study, the pupils who answered in the questionnaire that they had been advised to visit Niigata University Hospital after the school screening were defined as Scoliosis group (51 pupils; 0.159%) and the others were defined as No scoliosis group (32,083 pupils). The point and lifetime prevalence of back pain, the duration, the recurrence, the severity and the location of back pain were compared between these groups.

The severity of back pain was divided into three levels (level 1 no limitation in any activity; level 2 necessary to refrain from participating in sports and physical activities, and level 3 necessary to be absent from school). The point prevalence was 11.4% in No scoliosis group, and 27.5% in Scoliosis group. The lifetime prevalence was 32.9% in No scoliosis group, and 58.8% in Scoliosis group. According to the gender- and school-grade-adjusted odds ratios (OR), Scoliosis group showed a more than twofold elevated odds of back pain compared to No scoliosis group irrespective of the point or lifetime prevalence of back pain (OR, 2.29; P = 0.009 and OR, 2.10; P = 0.012, respectively).

Scoliosis group experienced significantly more severe pain, and of a significantly longer duration with more frequent recurrences in comparison to No scoliosis group. Scoliosis group showed significantly more back pain in the upper and middle right back in comparison to No scoliosis group. These findings suggest that there is a relationship between pain around the right scapula in Scoliosis group and the right rib hump that is common in IS.

From the Full-Text Article:

Introduction:

Most patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) visit the hospital when a trunk deformity, such as rib or lumbar hump and waist asymmetry, is pointed out either after the school screening or by family members, and it is rare for these patients to visit the hospital due to back pain. However, some adolescent patients with idiopathic scoliosis (IS) do complaint of back pain in outpatient clinics. Previously, it had been accepted that special attention should be paid to patients with scoliosis who experienced back pain, because it was thought that might be additional pathologies such as an occult syrinx, spinal cord tumors, or neuromuscular disorders [4, 6, 20].

Regarding back pain in childhood and adolescents, previous studies showed that the point prevalence of back pain ranges from 12 to 33% [1, 2, 13, 14, 17, 19] and the lifetime prevalence of back pain varies between 30 and 51% [1–3, 10, 14, 17, 21]. It has been recognized that low back pain (LBP) is a common condition, with a high rate of occurrence not only in adults, but also in childhood and adolescents [1, 3, 5, 8, 9, 11, 17, 18, 22]. However, there have been a few studies regarding the details of back pain in adolescents with IS, with regard to the prevalence, severity and location of back pain [7, 12, 15, 16, 23, 24]. Previous studies showed a wide range prevalence of back pain in adolescents with IS, ranging 23–85% [7, 12, 15, 16, 23]. Some studies have indicated that the prevalence of back pain in adolescents with IS are similar to the general adolescent population [16], while other studies concluded that adolescents with IS experience more back pain and more severe back pain than their peers [12].

The purpose of this study was to clarify the condition of back pain in adolescent with IS using a large-scale cross-sectional epidemiological study based on a questionnaire administered to all children living in a defined area of Japan.

Materials and methods

The present study includes all schoolchildren consisting of a total of 43,630 pupils (22,356 males and 21,274 females), including all elementary school pupils from the fourth to sixth grade (110 schools: 21,893 pupils) and all junior high pupils from the first to third year (57 schools: 21,737 pupils) in Niigata City (at longitude 139° East and latitude 37° North, located on the West coast of Japan with an area of 649 km2 and a population of 785,067 as of September 30, 2005). In the Japanese school system, elementary school consists of a 6 year program including the first to sixth grades, while junior high school is a 3 year program comprising the first year, the second year and the third year levels. The fourth grade elementary school pupils thus correspond to children ranging 9–10 years of age (E4); the fifth grade children ranging 10–11 years of age (E5); and the sixth grade children ranging 11–12 years of age (E6). The first year junior high school pupils correspond to children ranging 12–13 years of age (J1); the second year pupils comprise children ranging 13–14 years of age (J2); and the third year pupils including children ranging 14–15 years of age (J3).

An anonymous questionnaire, which carefully protected any personal information, was made and distributed to each school. The questionnaire was taken home by all elementary school children to fill out together with their parents or guardians, and thereafter, they were collected at the school. For junior high school students, it was filled out by each of them and collected at the school. The data were collected from October 17, 2005 to November 11, 2005.

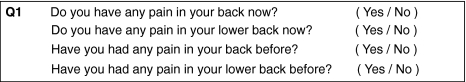

Figure 1 At first, basic information, such as the name of their school, their school-grade, gender, height, and weight were filled in on the answer form. Next, any experience of back pain was described by means of multiple choice answers in Question 1 of the questionnaire, with the options divided between the present and the past, and the details of back pain were continuously surveyed using the selection answer form for students who had experienced back pain (Figure 1).

Regarding the definition of back pain, there was no information for back pain in the questionnaire, and it depended only on their judgment as back pain. A valid response was the ones that had also appropriately answered their gender, school-grade, and Question 1. Responses to the questionnaire were received from 34,830 of 43,630 pupils (response rate 79.8%), and 32,134 pupils who were determined to have valid responses (valid response rate 73.7%).

Figure 2

Table 1

Figure 3 In Niigata City, pupils from the fourth grade of elementary school to the third year of junior high school are screened for scoliosis every year in early summer. This screening system involves a three-step survey, with the third-step of the survey being an imaging and medical examination in the Niigata University Hospital (Figure 2). A question about the school screening for scoliosis was included in the questionnaire. In this study, the pupils who answered in the questionnaire that they had been advised to visit Niigata University Hospital during the school screening were defined as Scoliosis group (0.159%; 51/32,134) (Table 1). The prevalence of scoliosis was significantly higher in females than in males, and increased along with the school-grade elevation.

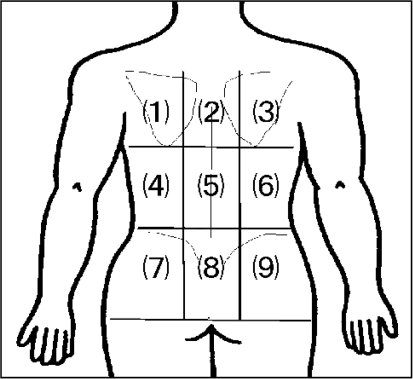

The point prevalence and the lifetime prevalence of back pain were evaluated in both Scoliosis and No scoliosis groups. Additionally, in pupils with a lifetime prevalence of back pain, the duration of back pain, the recurrence of back pain, the severity of back pain and the region of back pain were also evaluated. The severity of back pain was divided into three levels (level 1 no limitation in any activity; level 2 necessary to refrain from participating in sports and physical activities, and level 3 necessary to be absent from school). Regarding the location of back pain, the back was divided into nine parts, and the region in which subjects experienced their most severe back pain was selected (Fig. 3).

The SPSS software program (Version 14) for Windows was used to perform all statistical analyses; Fisher’s exact probability test was used for comparison of the gender and the location of back pain between Scoliosis and No scoliosis groups, and the Chi-square test was used for comparison of pain by school-grade. Binomial or multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to estimate gender- and school-grade-adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of back pain and its characteristic status associated with scoliosis. Gender- and school-grade were adjusted in these logistic models because there were significant differences in these distributions between the two groups (Table 1). In all the cases, statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Point prevalence and Lifetime prevalence of back pain

Table 2 The point and lifetime prevalence of back pain was higher in Scoliosis group than in No scoliosis group. (27.5 vs. 11.4% and 58.8 vs. 32.9%, respectively) (Table 2). According to gender- and school-grade-adjusted analyses, Scoliosis group showed a more than twofold elevated odds of back pain compared to No scoliosis group irrespective of the point or lifetime prevalence of back pain (OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.23–4.29; P = 0.009 and OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.18–3.72; P = 0.012, respectively).

Duration, recurrence and severity of back pain

Table 3 The various characteristics of back pain were analyzed among pupils with a lifetime prevalence of back pain (Table 3). Regarding the durations of back pain, the prevalence of “?1 week” was lower in Scoliosis group (38.7%) than in No scoliosis group (68.1%), although this duration was the most frequent in both groups. On the other hand, 35.5% of pupils in the Scoliosis group answered that they had experienced back pain which lasted “>3 months”: the prevalence was much higher than that in the No scoliosis group (7.7%). Accordingly, scoliosis was concluded to be significantly associated with an elevated OR of back pain lasted “>3 months” (OR against “?1 week”, 7.92; 95% CI, 3.39–18.51, P < 0.001).

Pupils in Scoliosis group more frequently experienced recurrent back pain (83.9%) than pupils in No scoliosis group (60.1%) (OR, 3.94; 95% CI, 1.37–11.36, P = 0.011).

As for the severity of back pain, in Scoliosis group, level 1 pain was reported by 66.7%, level 2 by 9.1% and level 3 by 24.2% of the pupils. In No scoliosis group, level 1 pain was reported by 80.5%, level 2 by 15.7% and level 3 by 3.8% of the pupils. Scoliosis group was thus significantly associated with an elevated OR of “Level 3” back pain (OR against “Level 1”, 7.92; 95% CI, 3.39–18.51, P < 0.001).

Location of back pain

Table 4 The most frequent location of the most severe back pain was region 8 (lower centre) in both of Scoliosis group (33.3%) and No scoliosis group (36.9%). Pupils in Scoliosis group more frequently experienced the most severe back pain in region 2 (upper centre), 3 (upper right) and 6 (middle right) than pupils in No scoliosis group (16.7 vs. 3.6%, P = 0.004; 30.0 vs. 5.7%, P < 0.001; and 16.7 vs 5.1%, P = 0.017, respectively) (Table 4).

Discussion

Recently, it has been recognized that LBP is a common condition, with a high rate of occurrence not only in adults, but also in childhood and adolescents [1, 3, 5, 8, 9, 11, 17, 18, 22]. Previous studies showed that the point prevalence of back pain varies ranges 12–33% [1, 2, 13, 14, 17, 19], and the lifetime prevalence of back pain varies between 30 and 51% [1–3, 10, 14, 17, 21]. On the other hand, there have been a few studies regarding the detail of back pain in adolescents with IS with regard to the prevalence, severity, and the location of back pain [7, 12, 15, 16, 23, 24] and the results were inconsistent, with wide range of life time prevalence, ranging 23–85% [7, 12, 15, 16, 23]. Ramirez et al. [16] reported a retrospective study of 2,442 patients (age 6–20 years) who had idiopathic scoliosis showing that the lifetime prevalence of back pain was 23% and the point prevalence of back pain was 9%. He concluded that these results were similar to the prevalence in the general pediatric and adolescent population reported by others. On the other hand, Pratt et al. [15] reported a questionnaire study of 39 patients treated surgically for AIS. Of these patients, 85% experienced some back pain at preoperative assessment, and this result was higher than the previous reports for healthy adolescents. Dickson et al. [7] also reported that back pain was significantly more prevalent among the 165 scoliosis subjects than among the 100 age- and sex-matched control subjects (73 vs. 52%) using a questionnaire survey (average age at survey was 17 years). In the present study, the point and lifetime prevalence in Scoliosis group were 27.5 and 58.8%, respectively, which both were significantly higher than in No scoliosis group. The pupils in Scoliosis group also experienced significantly more back pain, and had a longer duration and more recurrences of back pain in comparison to those in No scoliosis group. These results were consistent with those reported by Pratt [15] and Dickson [7].

Regarding the location of back pain in AIS, there have also been a few studies [7, 12, 23, 24]. Weinstein et al. [23] reported the location of back pain and the relationship between the curve pattern and pain severity, using a long-term follow up study for 194 untreated idiopathic scoliosis patients (average age at survey was 39.3 years). There was a tendency for the patients with a thoracic curve to have fewer back symptoms than those with other curve patterns (thoracic curve 25%, combined 43%, thoracolumbar 52%, lumbar 42%). However, the severity of the curve, regardless of the type, was not necessarily correlated with back symptoms. Regarding the location of tenderness in the back, the investigators divided the back into “the apex of the curve”, “the concavity of the curve”, “the interscapular region”, “the suprascapular region”, “the paraspinous muscle”, and “occasionally the lower ends of the ribs” (when they were in contact with the iliac crest). In their study, 45% of all patients experienced some tenderness in one or more areas as follows: localized tenderness at the concavity of the curve, diffuse paraspinous tenderness, tenderness over the rib hump, and tenderness in the interscapular and suprascapular regions. Dickson et al. [7] reported that back pain occurred more frequently in the interscapular and thoracolumbar regions in AIS patients compared with the control group, and that there was no association between back pain and the type of curve or the degree of curvature. In the present study, because of the lack of clinical data regarding scoliosis, such as the magnitude of the curve and which type of scoliosis was included in Scoliosis group, it was impossible to evaluate the relationship between back pain and these features more fully. However, regarding the location of back pain, our data provided interesting results. The pupils in Scoliosis group showed significant back pain in the upper and middle right back in comparison to No scoliosis group. Because many IS patients have a right convex thoracic curve with a right rib hump in their back, our results suggest that there is a relationship between the pain around the right scapula and the rib hump.

Although our study provided some interesting information regarding back pain in adolescents with IS, there are several limitations. First, the definition of back pain used in this study might be insufficient, because it was dependent on pupils’ judgment, which could potentially lead to some bias. Particularly, for elementary school pupils, it might be difficult to understand the meaning of back pain and the precise details of back pain. As a result, the questionnaire were taken home and filled out with the assistance of their parents or guardians. Second, the definition of Scoliosis group was only based on the results of the questionnaire. There might be false positive and negative cases in school screenings, and some pupils in Scoliosis group might not have had scoliosis, while some pupils in No scoliosis group might have had the condition. Third, this questionnaire survey was performed after the school screening for scoliosis. Therefore, for the pupils in Scoliosis group who were advised to visit Niigata University Hospital to undergo comprehensive physical examination at the time of the survey, the possibility that such pupils had a higher consciousness regarding back pain than No scoliosis group could not be ruled out.

Conclusion:

We conducted a large-scale cross-sectional study using a questionnaire to elucidate the details of back pain in adolescents with IS. The point and lifetime prevalence of back pain were significantly higher in Scoliosis group in comparison to No scoliosis group. The pupils in Scoliosis group experienced significantly more severe back pain, with a longer duration and more recurrences in comparison to those in No scoliosis group. In addition, the pupils in Scoliosis group showed significant more back pain in the upper and middle right back in comparison to those in No scoliosis group. These findings suggest that there may be a relationship between pain around the right scapula and the rib hump that is common in IS.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank the members of the Niigata City board of education and others associated with the elementary schools and junior high schools in Niigata City for their valuable cooperation in making this study.

Conflict of interest

None.References:

Balagué F, Dutoit G, Waldburger M.

Low back pain in schoolchildren. An epidemiological study.

Scand J Rehabil Med. 1988;20:175–179Balagué F, Nordin M, Skovron ML, Dutoit G, Yee A, Waldburger M.

Non-specific low-back pain among schoolchildren: a field survey with analysis of some associated factors.

J Spinal Disord. 1994;7:374–379Balagué F, Skovron ML, Nordin M, Dutoti G, Pol LR, Waldburger M.

Low back pain in schoolchildren–A study of familial and psychological factors.

Spine. 1995;20:1265–1270Barnes PD, Brody JD, Jaramillo D, Akbar JU, Emans JB.

Atypical idiopathic scoliosis: MR imaging evaluation.

Radiology. 1993;186:247–253Burton AK, Clarke RD, McClune TD, Tillotson KM.

The natural history of low back pain in adolescents.

Spine. 1996;21:2323–2328Coonrad RW, Richardson WJ, Oakes WJ.

Left thoracic curves can be different.

Orthop Trans. 1985;9:126–127Dickson JH, Erwin WD, Rossi D.

Harrington instrumentation and arthrodesis for idiopathic scoliosis. A twenty-one year follow-up.

J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:678–683Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO, Manniche CM.

The Course of Low Back Pain from Adolescence to Adulthood: Eight-year Follow-up of 9600 Twins

Spine 2006 (Feb 15); 31 (4): 468–472Jones MA, Stratton G, Reilly T, Unnithan VB.

A school-based survey of recurrent non-specific low-back pain prevalence and consequences in children.

Health Educ Res. 2004;19:284–289Kristjandorrir G.

Prevalence of self-reported back pain in school children: a study of sociodemographic differences.

Eur J Pediatr. 1996;155:984–986Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO.

At What Age Does Low Back Pain Become a Common Problem? A Study of 29,424 Individuals

Aged 12-41 Years

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998 (Jan 15); 23 (2): 228–234Mayo NE, Goldberg MS, Poitras B, Scott S, Henley J.

The Ste-justin adolescent idiopathic scoliosis cohort study. Part III: back pain.

Spine. 1994;19:1573–1581Nissinen M, Heliovaara M, Seitsamo J, Alaranta H, Poussa M.

Anthropometric measurements and the incidence of low back pain in a cohort of pubertal children.

Spine. 1994;12:1367–1370Olsen TL, Anderson RL, Dearwater SR, Kriska AM, Cauley JA, Aaron DJ, LaPorte RE.

The epidemiology of low-back pain in an adolescent population.

Am J Public Health. 1992;82:606–608Pratt RK, Burwell RG, Cole AA, Webb JK.

Patient and parental perception of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis before and after surgery in comparison with surface and radiographic measurements.

Spine. 2002;27:1543–1550Ramirez N, Johnston CE, Browne RH.

The prevalence of back pain in children who have idiopathic scoliosis.

J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:364–368Salminen JJ, Pentti J, Terho P.

Low back pain and disability in 14-year-old schoolchiidren.

Acta Paediatr. 1992;81:1035–1039Sato T, Ito T, Hirano T, Morita O, Kikuchi R, Endo N, Tanabe N.

Low back pain in childhood and adolescence: a cross-sectional study in Niigata City.

Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1441–1447Taimela S, Kujala UM, Salminen JJ, Viljanen T.

The prevalence of low back pain among children and adolescents. A nationwide, cohort-based questionnaire survey in Finland.

Spine. 1997;22:1132–1136Thompson GH.

Back pain in children.

J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:928–938Troussier B, Davoine B, Gaudemaris R, Foconni J, Phélip X.

Back pain in school children. Study among 1178 people.

Scand J Rehabil Med. 1994;26:143–146Watson KD, Papageorgiou AC, Jones GT, Taylor S, Symmons DPM, Silman AJ, Macfarlane GJ.

Low back pain in schoolchildren: occurrence and characteristics.

Pain. 2002;97:87–92Weinstein SL, Zavala DC, Ponseti IV.

Idiopathic scoliosis. Long-term follow-up and prognosis in untreated patients.

J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:702–712Weinstein SL.

Natural history.

Spine. 1999;24:2592–2600

Return to SCOLIOSIS

Since 6-29-2015

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |