The Association Between Use of Chiropractic Care and

Costs of Care Among Older Medicare Patients With

Chronic Low Back Pain and Multiple ComorbiditiesThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Feb); 39 (2): 6375 ~ FULL TEXT

William B Weeks, MD, PhD, MBA, Brent Leininger, DC, James M Whedon, DC, MS,

Jon D Lurie, MD, MS, Tor D Tosteson, ScD, Rand Swenson, DC, MD, PhD,

Alistair J OMalley, PhD, Christine M Goertz, PhD, DC

The Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth,

The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice,

Director, Health Services and Clinical Research, Palmer College of Chiropractic,

Palmer Center for Chiropractic Research,

Davenport, IA

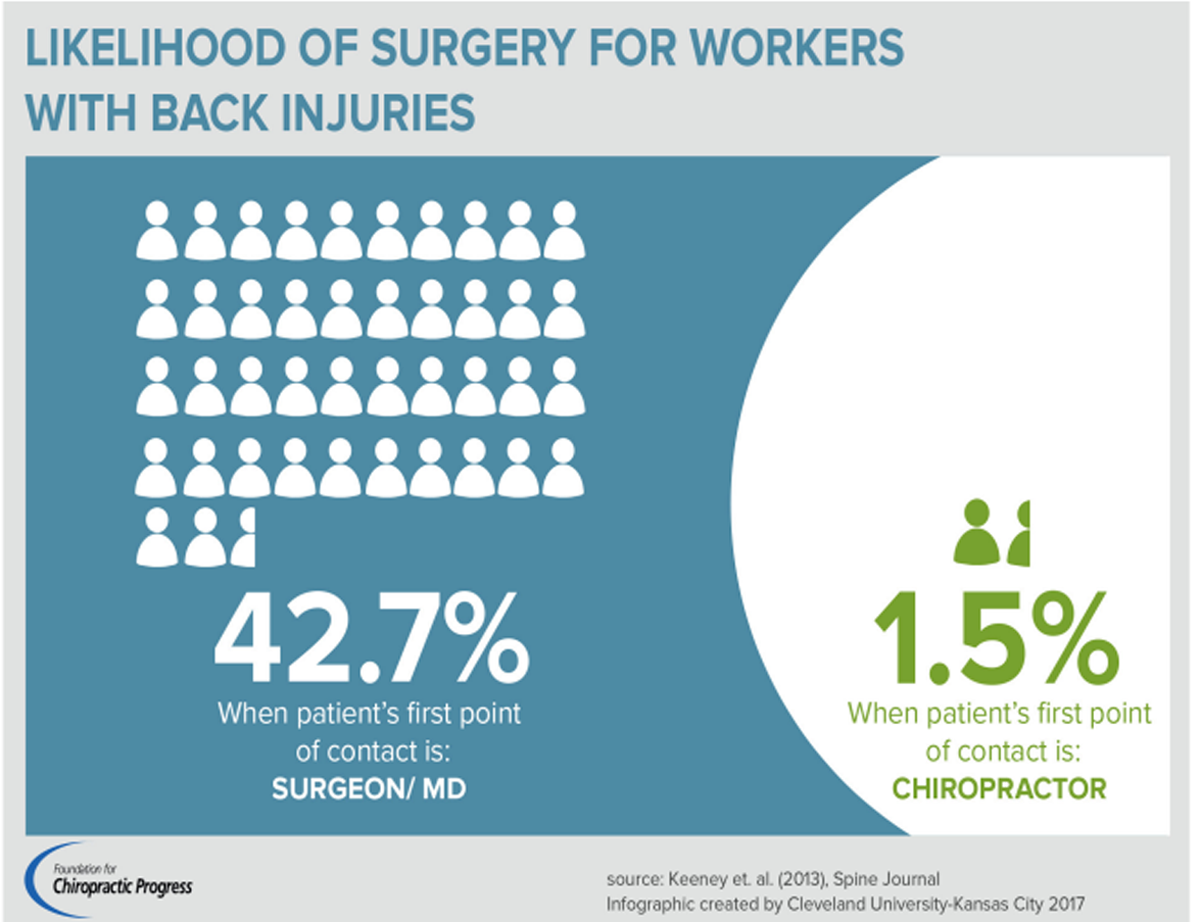

FROM: Keeney ~ Spine 2013 (May 15)OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to determine whether use of chiropractic manipulative treatment (CMT) was associated with lower healthcare costs among multiply-comorbid Medicare beneficiaries with an episode of chronic low back pain (cLBP).

METHODS: We conducted an observational, retrospective study of 2006 to 2012 Medicare fee-for-service reimbursements for 72,326 multiple-comorbid patients aged 66 and older with cLBP episodes and 1 of 4 treatment exposures: chiropractic manipulative treatment (CMT) alone, CMT followed or preceded by conventional medical care, or conventional medical care alone. We used propensity score weighting to address selection bias.

RESULTS: After propensity score weighting, total and per-episode day Part A, Part B, and Part D Medicare reimbursements during the cLBP treatment episode were lowest for patients who used CMT alone; these patients had higher rates of healthcare use for low back pain but lower rates of back surgery in the year following the treatment episode. Expenditures were greatest for patients receiving medical care alone; order was irrelevant when both CMT and medical treatment were provided. Patients who used only CMT had the lowest annual growth rates in almost all Medicare expenditure categories. While patients who used only CMT had the lowest Part A and Part B expenditures per episode day, we found no indication of lower psychiatric or pain medication expenditures associated with CMT.

CONCLUSIONS: This study found that older multiple-comorbid patients who used only CMT during their cLBP episodes had lower overall costs of care, shorter episodes, and lower cost of care per episode day than patients in the other treatment groups. Further, costs of care for the episode and per episode day were lower for patients who used a combination of CMT and conventional medical care than for patients who did not use any CMT. These findings support initial CMT use in the treatment of, and possibly broader chiropractic management of, older multiply-comorbid cLBP patients.

KEYWORDS: Chiropractic; Manipulation; Medicare; Propensity Score; Retrospective Studies

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Controlling the growth of healthcare costs continues to be a critical health policy issue. An aging population and advances in the ability to extend life and manage chronic disease have conspired to produce approximately 75 million people in the US who have multiple concurrent chronic conditions [1, 2]: 62% of Americans over age 65 have multiple chronic conditions, [3] and 23% of Medicare beneficiaries have 5 or more chronic conditions. [4] The care of individuals with chronic conditions is estimated to account for 78% of US healthcare spending, and Medicare beneficiaries with more than 1 chronic condition account for 95% while those with more than 5 chronic conditions account for 66% of all Medicare spending. [3] The likelihood that patients will use expensive health care resources such as hospital care increases substantially when comorbidities are present, [5, 6] and resource consumption increases dramatically if patients are also depressed. [7] The Strategic Framework on Multiple Chronic Conditions has called for development of new models of care for multiply comorbid Medicare beneficiaries. [8]

In addition, it has become increasingly evident that chronic pain is associated with high rates of diagnosable psychopathology, [9] and that unrecognized and untreated psychopathology can interfere with rehabilitation. [10] Because anxiety can decrease pain thresholds and tolerance, [11] emotional distress can magnify medical symptoms, [12] and depression can worsen chronic pain treatment outcomes, [13] psychiatric comorbidities may be implicated in perpetuating pain-related dysfunction. [14]

Among older US adults, back pain is common and associated with co-morbidities and self-reported difficulty with most functional tasks. [15] Medicare data from the 1990s indicated that low back pain (LBP) diagnoses and related expenditures increased disproportionately, [16] the use of lumbar and facet injections for LBP increased dramatically, [17] and there was intensive use of pharmaceutical agents among LBP patients. [18] The escalating prevalence of LBP among Medicare beneficiaries, the increasing costs of its treatment, and the high use and costs of pharmaceuticals suggest a critical need to identify appropriate, cost-effective, and conservative treatments for older patients with LBP. Further, the tenacity and cost of chronic pain disorders, and the very high rates of comorbid depression, [19, 20] undiagnosed mood disorders (reaching levels of 75% among those with cLBP), [21, 22] and anxiety disorders [19, 20, 23] with chronic pain disorders suggest that exploring ways to disrupt the vicious cycle of pain, stress, and emotional dysfunction are warranted. Since simultaneous pharmacological treatment of pain symptoms and major depression has led to improved function and quality of life, [24] and longitudinal analyses have shown that changes in pain and depression symptoms influence 1 another, [25, 26] it makes sense that concurrent treatment of both conditions is recommended. [10]

Most LBP in older adults can be managed non-surgically, [16] and randomized controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that chiropractic manipulative treatment (CMT) is an effective, conservative treatment option for LBP [2730] that has been recommended for back pain in older adults by a variety of advisory bodies. [31, 32] While CMT has been shown to result in slightly better pain and function outcomes compared to other active treatments for chronic LBP, a number of researchers have questioned the clinical importance of these findings. From a healthcare system or societal perspective, small differences in clinical outcomes may be important if associated with minimal additional costs, or cost savings. Studies examining differences in healthcare expenditures between CMT users and non-users show that CMT users are younger, wealthier, and healthier than non-users. [3335] After propensity score matching to adjust for such differences, 1 study of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey found that chiropractic care was associated with a lower use of medical resources, overall. [36] However, to date, propensity score methods have not been applied to claims data for the purposes of evaluating costs of care for multiply-comorbid patients seeking CMT for treatment of LBP.

Therefore, to explore whether older Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with an episode of LBP and multiple comorbidities who obtained CMT during their episode had lower costs than those who did not, we used Medicare files and a propensity score weighting methodology to adjust for confounders and create equivalent groups for comparison. [3740] Further, we sought to determine whether, for particular diagnostic mixes within these treatment groups, reduced expenditures on psychiatric care or pain medications might be associated with CMT

Discussion

We examined 4 clinical treatment patterns for older, Medicare fee-for-service enrolled, multiply-comorbid patients who had a discrete episode of cLBP. After propensity score weighting that addressed differences in demographics across the treatment groups (including the finding that CMT patients had lower illness burdens), we found that patients who used only CMT during their cLBP episodes had lower overall costs of care, shorter episodes, and lower cost of care per episode day than patients in the other treatment groups.

Further, costs of care for the episode and per episode day were lower for patients who used a combination of CMT and conventional medical care than for patients who did not use any CMT, although most cost differences were due to differences in inpatient care cost; Medicare part B and D expenditures for patients who used any conventional medical care for their cLBP were similar, as were compound annual expenditure growth rates. While costs of care, and annual growth of healthcare costs, were generally lower for patients who used only CMT, that advantage might be offset somewhat by higher rates of later treatment for chronic LBP within a year of the episodes completion in this group.

A high proportion of CMT users had 13 or more chiropractic visits. Others have found substantial variation in the number and duration of episodes of chiropractic care and the number of visits associated with those episode. [43, 47] However, the potential overall (and particularly pain medication) cost savings that we found when only DCs provided back pain treatment for patients with cLBP might warrant further exploration of a new role for DCs in managing such multiply-comorbid patients. [48, 49]

In contrast to other studies results, [42, 43] we did not find that order of treatment was associated with large differences in treatment costs of care when both CMT and conventional medical care were used during an episode of care. This might be attributable to the fact that we examined a multiply-comorbid cohort of patients. We did find modestly higher daily Part B and Part D costs for patients who used conventional medical care before they used CMT, but this cost advantage was offset by longer episode lengths when CMT was obtained first.

We sought evidence that CMT might reduce expenditures for psychiatric care or pain medications among older Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with a cLBP episode who had an additional NMS diagnosis and anxiety, depression, or both. However, we found no reductions in psychiatric expenditures associated with CMT. While we found reductions in overall and pain medication expenditures associated with CMT at the episode level, these disappeared when examining those expenditures on a per-episode-day basis. We did find evidence that patients with osteoarthritis were less likely, and those with other NMS diagnoses were more likely, to use CMT; however, this may reflect that doctors of chiropractic and doctors of medicine have different coding practices.

Clinical and Policy Application

Our findings suggest that, from a Medicare cost standpoint, CMT may be a cost-efficient first line treatment choice for older, multiply-comorbid patients with cLBP. If policymakers encouraged DCs to have a greater role in initially managing such patients, patients may have episodes of care that were shorter and less costly (both overall and per episode day), and they might have lower pharmaceutical expenditures for pain medications. Further, should such management require the addition of conventional medical care after an initial course of CMT, policymakers might expect that overall costs might be similar to those for episodes wherein CMT was added after conventional medical care.

Limitations and Future Studies

Our study has several limitations. First, findings from the multiply-comorbid group that we examined may not be generalizable either to the larger Medicare fee-for-service population or to the US population. Second, we were constrained by the use of large Medicare datasets. While these datasets generated relatively large numbers of patients in the 4 treatment groups and reflect actual care utilization patterns, we were unable to determine whether care provided was justified or resulted in better health outcomes, as determined by patients. Third, when patients choose a particular treatment, there exists the potential for selection bias due to unmeasured confounders. While we attempted to address selection bias through inverse propensity score weighting, ours is not a randomized controlled trial, and so there is no guarantee that the distributions of any unmeasured risk factors do not vary between the weighted groups. Therefore, all findings are referred to as associations and do not necessarily imply causality. Finally, we analyzed discrete, defined episodes of cLBP; analyses that use other definitions of cLBP may generate different results. Studies such as ours provide initial evidence that CMT use is associated with lower expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries with cLBP and multiple co-morbidities. While the study design limits our ability to make strong conclusions, future exploration of causation through randomized controlled trials is warranted; such studies might be a reasonable next step in determining the most effective and efficient treatment for this multiply-comorbid and costly group of patients. Also, while we did not find reductions in expenditures for psychiatric or pain medication associated with CMT in this population, that patients who used only CMT had lower overall and per day Part A and Part B expenditures suggests that cost savings might be found in other areas. Future work should examine broader and younger populations, where such cost savings might be more readily found. Finally, future studies should attempt to examine patient centered health outcomes so that cost-effectiveness analyses could be conducted.

Conclusion

We found that older multiply-comorbid patients who used only CMT during their cLBP episodes had lower overall costs of care, shorter episodes, and lower cost of care per episode day than patients in the other treatment groups. Further, costs of care for the episode and per episode day were lower for patients who used a combination of CMT and conventional medical care than for patients who did not use any CMT. These findings support initial CMT use in the treatment of, and possibly broader chiropractic management of, older multiply-comorbid cLBP patients.

Practical Applications

Among older, multiply-comorbid Medicare beneficiaries with a chronic low back pain episode, chiropractic manipulative treatment was associated with lower overall episode costs and lower episode costs per day.

Most multiply-comorbid chronic low back patients who used any chiropractic manipulative treatment had at least 6 chiropractic visits; most of those who exclusively used chiropractic manipulative treatment had more than 12 visits.

Use of chiropractic manipulative treatment was associated with lower total Part A and Part D Medicare cost growth for multiply-comorbid patients with chronic low back pain episodes over the time period examined.

While we found overall Medicare cost-savings associated with use of chiropractic care, we found no evidence of lower psychiatric or pain medication expenditures associated with chiropractic manipulative treatment within diagnostic subgroups.

References:

Vogeli, C, Shields, AE, Lee, TA et al.

Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications

for quality, care management, and costs.

J Gen Intern Med. 2007; 22: 391395Parekh, AK and Barton, MB.

The challenge of multiple comorbidity for the US health care system.

JAMA. 2010; 303: 13031304Partnership for Solutions Chronic Conditions:

Making the Case for Ongoing Care.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton; 2002Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America.

Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century

Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001Braunstein, JB, Anderson, GF, Gerstenblith, G et al.

Noncardiac comorbidity increases preventable hospitalizations and mortality

among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic heart failure.

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 42: 12261233Niefeld, M, Braunstein, JB, Wu, AW, Saudek, CD,

Weller, W, and Anderson, GF.

Preventable hospitalization among elderly Medicare beneficiaries

with type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes Care. 2003; 26: 13441349Himelhoch, S, Weller, W, Wu, AW,

Anderson, GF, and Cooper, L.

Chronic medical illness, depression, and use of acute medical services

among Medicare beneficiaries.

Med Care. 2004; 42: 512521Parekh, AK, Kronick, R, and Tavenner, M.

Optimizing health for persons with multiple chronic conditions.

JAMA. 2014; 312: 11991200Dersh, J, Polatin, PB, and Gatchel, RJ.

Chronic pain and psychopathology: research findings and theoretical considerations.

Psychosom Med. 2002; 64: 773786Gatchel, RJ.

Psychological disorders and chronic pain: cause and effect relationships.

in: RJ Gatchel, DC Turk (Eds.)

Psychological approaches to pain management: a practioner's handbook.

Guilford Publications, New York; 1996: 3354Cornwal, A and Doncleri, DC.

The effect of experimental induced anxiety on the experience of pressure pain.

Pain. 1988; 35Katon, W.

The impact of major depression on chronic medical illness.

Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996; 18: 215219Burns, J, Johnson, B, Mahoney, N, Devine, J, and Pawl, R.

Cognitive and physical capacity process variables predict long-term outcome

after treatment of chronic pain.

J Clin Consult Psychiatry. 1998; 66: 434439Holzberg, AD, Robinson, ME, Geissner, ME, and Gremillion, HA.

The effects of depression and chronic pain on psychosocial and physical functioning.

Clin J Pain. 1996; 12: 118125Weiner, DK, Haggerly, CL, Kritchevsky, SB et al.

How does low back pain impact physical function in independent, well-functioning

older adults? Evidence from the Health ABC Cohort and implications for the future.

Pain Med. 2003; 4: 311320Weiner, DK, Kim, YS, Bonino, P, and Wang, T.

Low back pain in older adults: are we utilizing healthcare resources wisely?.

Pain Med. 2006; 7: 143150Friedly, J, Chan, L, and Deyo, R.

Increases in lumbosacral injections in the Medicare population: 19942001.

Spine. 2007; 32: 17541760Solomon, DH, Avorn, J, Wang, PS et al.

Prescription opiod use among older adults with arthritis or low back pain.

Arthritis Rheum. 2006; 55: 3541Gore M, Sadosky A, Stacey BR, Tai KS, Leslie D.

The Burden of Chronic Low Back Pain: Clinical Comorbidities, Treatment Patterns,

and Health Care Costs in Usual Care Settings

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 (May 15); 37 (11): E668677Gerrits, MM, Vogelzangs, N, van Oppen, P,

van Marwijk, HW, van der Horst, H, and Penninx, BW.

Impact of pain on the course of depressive and anxiety disorders.

Pain. 2012; 153: 429436Salazar, A, Duenas, M, Mico, JA et al.

Undiagnosed mood disorders and sleep disturbances in primary care patients with

chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Pain Med. 2013; 14: 14161425Olaya-Contreras, P and Styf, J.

Biopsychosocial function analyses changes the assessment of the ability to work

in patients on long-term sick-leave due to chronic musculoskeletal pain:

the role of undiagnosed mental health comorbidity.

Scand J Public Health. 2013; 41: 247255Ritzwoller, DP, Crounse, L, Shetterly, S, and Rublee, D.

The association of comorbidities, utilization and costs from patients

identified with low back pain.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006; 7: 72Wygant, EG.

Relief of depression in patients with chronic diseases.

Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1966; 8: 363372Kroenke, K, Wu, J, Bair, MJ, Krebs, EE,

Damush, TM, and Tu, W.

Reciprocal relationship between pain and depression: a 12-month longitudinal

analysis in primary care.

J Pain. 2011; 12: 964973Myhr, A and Augestad, LB.

Chronic pain patients--effects on mental health and pain after a 57-week

multidisciplinary rehabilitation program.

Pain Manag Nurs. 2013; 14: 7484Rubinstein, SM, van Middelkoop, M, Assendelft, WJ,

de Boer, MR, and van Tulder, MW.

Spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low-back pain.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011; 2: CD008112Furlan, AD, Yazdi, F, Tsertsvadze, A et al.

Complementary and Alternative Therapies for Back Pain II

Evidence/Technology Report Number 194

AHRQ Publication No. 10(11)-E007 (October 2010),

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MDWalker, BF, French, SD, and Grant, W.

A Cochrane review of combined chiropractic interventions for low-back pain.

Spine. 2011; 36: 230242Walker, BF, French, SD, Grant, W, and Green, S.

Combined chiropractic interventions for low-back pain.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011; 14: CD005427Chou, R., Qaseem, A., Snow, V., Casey, D., Cross, J. T.,

Shekelle, P., & Owens, D. K.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline

from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society

Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 478491American Geriatrics Society.

The management of chronic pain in older persons:

AGS Panel on Chronic Pain in Older Persons.

J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998; 46: 635651Ndetan, HT, Bae, S, Evans, MW, Rupert, RL, and Singh, KP.

Characterization of health status and modifiable risk behavior among United States adults using chiropractic care as compared with general medical care.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009; 32: 414422Stano, M and Smith, M.

Chiropractic and Medical Costs of Low Back Care

Med Care 1996 (Mar); 34 (3): 191204Haas M, Sharma R, Stano M.

Cost-effectiveness of Medical and Chiropractic Care for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005 (Oct); 28 (8): 555563Martin, BI, Gerkovich, MM, Deyo, RA et al.

The Association of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use and Health Care Expenditures

for Back and Neck Problems

Medical Care 2012 (Dec); 50 (12): 10291036Patorno, E, Glynn, RJ, Hernandez-Diaz, S, Liu, J, and Schneeweiss, S.

Studies with many covariates and few outcomes: selecting covariates

and implementing propensity-score-based confounding adjustments.

Epidemiology. 2014; 25: 268278Rassen, JA, Shelat, AA, Franklin, JM, Glynn, RJ,

Solomon, DH, and Schneeweiss, S.

Matching by propensity score in cohort studies with three treatment groups.

Epidemiology. 2013; 24: 401409Suh, HS, Hay, JW, Johnson, KA, and Doctor, JN.

Comparative effectiveness of statin plus fibrate combination therapy and

statin monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: use of propensity-score

and instrumental variable methods to adjust for treatment-selection bias.

Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012; 21: 470484Weeks, WB, Tosteson, TD, Whedon, JM et al.

Comparing Propensity Score Methods for Creating Comparable Cohorts of Chiropractic Users and Nonusers

in Older, Multiply Comorbid Medicare Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015 (Nov); 38 (9): 620628Rozenberg, S.

Chronic low back pain: definition and treatment.

Rev Prat. 2008; 58: 265272Liliedahl RL, Finch MD, Axene DV, Goertz CM.

Cost of Care for Common Back Pain Conditions Initiated With Chiropractic

Doctor vs Medical Doctor/Doctor of Osteopathy as First Physician:

Experience of One Tennessee-Based General Health Insurer

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010 (Nov); 33 (9): 640643Weigel, PAM, Hockenberry, JM, Bentler, SE, Kaskie, B, and Wolinsky, FD.

Chiropractic Episodes and the Co-occurrence of Chiropractic

and Health Services Use Among Older Medicare Beneficiaries

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2012 (Mar); 35 (3): 168-175Weeks, WB, Whedon, JM, Toler, A, and Goertz, CM.

Medicare's Demonstration of Expanded Coverage for Chiropractic Services:

limitations of the Demonstration and an alternative direct cost estimate.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2013; 36: 468481Coulter, ID, Hurwitz, EL, Adams, AH, Genovese, BJ,

Hays, R, and Shekelle, PG.

Patients Using Chiropractors in North America:

Who Are They, and Why Are They in Chiropractic Care?

SPINE (Phila Pa 1976) 2002; 27 (3) Feb 1: 291298Rassen, JA, Glynn, RJ, Brookhart, MA, and Schneeweiss, S.

Covariate selection in high-dimensional propensity score analyses of

treatment effects in small samples.

Am J Epidemiol. 2011; 173: 14041413Whedon JM, Song Y, Davis MA.

Trends in the Use and Cost of Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation Under Medicare Part B

Spine J. 2013 (Nov); 13 (11): 14491454Davis, MA, Whedon, JM, and Weeks, WB.

Complementary and alternative medicine practitioners and Accountable Care

Organizations: the train is leaving the station.

J Altern Complement Med. 2011; 17: 669674Paskowski I, Schneider M, Stevens J, Ventura JM, Justice BD.

A Hospital-Based Standardized Spine Care Pathway:

Report of a Multidisciplinary, Evidence-Based Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2011 (Feb); 34 (2): 98106

Further ReadingCherkin, DC, Deyo, RA, Volinn, E, and Loeser, JD.

Use of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM) to identify

hospitalization for mechanical low back problems in administrative databases.

Spine. 1992; 17: 817825Martin, BI, Deyo, RA, Mirza, SK et al.

Expenditures and Health Status Among Adults With Back and Neck Problems

JAMA 2008 (Feb 13); 299 (6): 656664Deyo, RA, Cherkin, DC, and Ciol, MA.

Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases.

J Clin Epidemiol. 1992; 45: 613619Iezzoni, L.

Risk Adjustment for Measuring Healthcare Outcomes. 4th ed.

Health Administration Press, Chicago, IL; 2012The Dartmouth Atlas Project.

(Accessed October 1, 2012, at)

http://www.dartmouthatlas.orgWhedon, JM and Song, Y.

Geographic variations in availability and use of chiropractic under Medicare.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012; 35: 101109Whedon JM, Song Y, Davis MA, Lurie JD.

Use of Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation in Older Adults is Strongly Correlated with Supply

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 (Sep 15); 37 (20): 17711777

Return to MEDICARE

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to COST-EFFECTIVENESS

Return to INITIAL PROVIDER/FIRST CONTACT

Since 2-26-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |