Deconstructing Chronic Low Back Pain in the Older Adult- Step by Step

Evidence and Expert-Based Recommendations for Evaluation and Treatment:

Part XI: DementiaThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Pain Medicine 2016 (Nov); 17 (11): 1993–2002 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Rollin Wright, MD, Monica Malec, MD, Joseph W. Shega, MD, Eric Rodriguez, MD,

Joseph Kulas, PhD, Lisa Morrow, PhD,Juleen Rodakowski, OTD, MS, OTR/L,

Todd Semla, PharmD, MS, AGSF, and Debra K. Weiner, MD

Section of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine,

Department of Medicine,

University of Chicago,

Chicago, Illinois.OBJECTIVE: To present the 11th in a series of articles designed to deconstruct chronic low back pain (CLBP) in older adults. The series presents CLBP as a syndrome, a final common pathway for the expression of multiple contributors rather than a disease localized exclusively to the lumbosacral spine. Each article addresses one of 12 important contributions to pain and disability in older adults with CLBP. This article focuses on dementia.

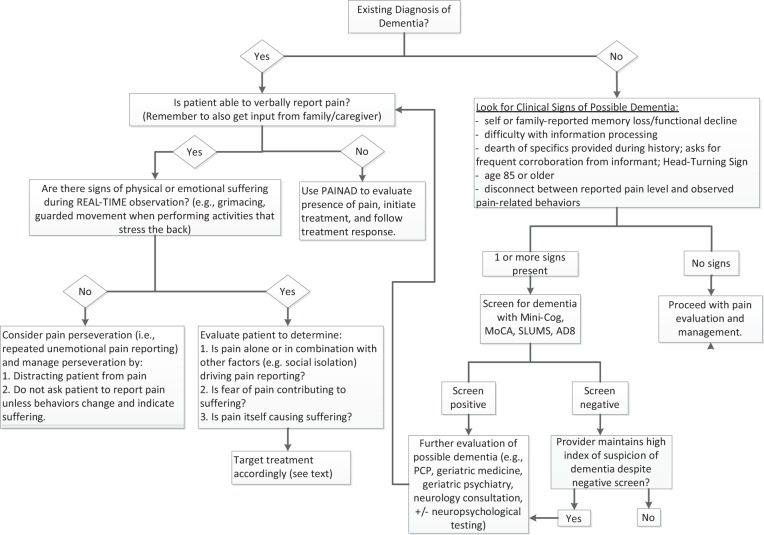

METHODS: A modified Delphi technique was used to develop an algorithm for an approach to treatment for older adults living with CLBP and dementia. A panel of content experts on pain and cognition in older adults developed the algorithm through an iterative process. Though developed using resources available within Veterans Health Administration (VHA) facilities, the algorithm is applicable across all health care settings. A case taken from the clinical practice of one of the contributors demonstrates application of the algorithm.

RESULTS: We present an evidence-based algorithm and biopsychosocial rationale to guide providers evaluating CLBP in older adults who may have dementia. The algorithm considers both subtle and overt signs of dementia, dementia screening tools to use in practice, referrals to appropriate providers for a complete a workup for dementia, and clinical considerations for persons with dementia who report pain and/or exhibit pain behaviors. A case of an older adult with CLBP and dementia is presented that highlights how an approach that considers the impact of dementia on verbal and nonverbal pain behaviors may lead to more appropriate and successful pain management.

CONCLUSIONS: Comprehensive pain evaluation for older adults in general and for those with CLBP in particular requires both a medical and a biopsychosocial approach that includes assessment of cognitive function. A positive screen for dementia may help explain why reported pain severity does not improve with usual or standard-of-care pain management interventions. Pain reporting in a person with dementia does not always necessitate pain treatment. Pain reporting in a person with dementia who also displays signs of pain-associated suffering requires concerted pain management efforts targeted to improving function while avoiding harm in these vulnerable patients.

KEYWORDS: Dementia; Chronic Pain; Low Back Pain; Lumbar; Primary Care.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Pain and dementia are common conditions that increase in frequency with age. [1–3] Pain in older adults tends to be underreported and undertreated compared to pain in younger adults. [4] At the same time, dementia is common and often under-recognized by clinicians. Dementia afflicts as many as 50% of those age 85 and older in the United States [5] and it can directly impact pain assessment and management. [3, 6]

Figure 1

Table 1 The cornerstone of chronic pain management is an assessment to identify the multiple medical and psychosocial factors potentially contributing to pain and functional impairment [7], and this includes assessment of cognitive function for many older adults. In patients not already known to have dementia, indicators that should prompt cognitive assessment to screen for dementia include: self or family report of memory loss, difficulty processing information during the clinical encounter, inability to report specific details during the pain history necessitating additional input from a caregiver, older than age 85, or a discrepancy between reported pain and observed pain-related behaviors (see Figure 1 and Table 1). [5, 8–10] Patients can be screened for dementia using one of several measures that are brief and easy to use, such as the Mini-Cog, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Saint Louis University Mental Status examination (SLUMS) (see Table 1). [11–13] Patients with a positive screen merit further evaluation for possible dementia and may include a referral for a more comprehensive cognitive evaluation that would be incorporated as part of the pain management plan.

The burden of chronic low back pain (CLBP) in older adults with dementia is unknown. However, dementia is likely to alter pain management because it alters pain reporting, pain behaviors, and pain coping. [14] Some evidence suggests that older adults with dementia report pain nearly as often as cognitively intact older adults. [15, 16] Furthermore, the multidimensional experience surrounding pain appears similar in persons with and without dementia. [17] The expression of pain or behaviors surrounding pain, however, may differ meaningfully. Many patients with dementia can report pain reliably [18], and we are taught that patient self-report is the gold standard. In all patients with CLBP, however, validation of pain self-report with behavioral observation is critical. If the patient with dementia reports 8/10 pain and demonstrates no behavioral manifestations of pain, it is possible that their pain verbalization represents simply perseveration, and additional pain treatment may not be required. Patients in pain may present in myriad ways, and no presentation either validates or invalidates the pain experience. Any disconnect between pain reporting and pain behavior should be further explored. In such patients, real-time assessment of pain during daily activities that the patient reports cause pain, such as walking, can provide key information regarding whether pain-focused treatment is needed.

Evidence also indicates that some persons with dementia and pain exhibit agitation and anxiety more often than persons with dementia who are not in pain. [19] Persons in the moderate-to-advanced stages of dementia may lose language skills and ability to verbally express their pain, and they may communicate pain through behaviors (e.g., grimacing, yelling, or bracing), anxiety, and/or agitation. In fact, anxiety and agitation may represent the only clues that a person with dementia is in pain. Failure to consider pain as a potential source of agitation can lead to the overuse of anxiolytics and antipsychotics to control these behaviors. [20] For these reasons, assessment of pain in persons with dementia must extend beyond a simple “yes or no” question about pain. Based on our clinical experience caring for patients with CLBP and dementia, this type of oversimplification often leads to inadequate pain assessment and management. A standardized approach to assessment in nonverbal dementia patients includes evaluation during painful conditions or procedures, observation of pain behaviors using a validated assessment tool, proxy report of behaviors that indicate pain, and an analgesic trial. [21]

The presence of dementia significantly impacts pain management because it alters pain reporting, pain behaviors, and pain coping. It also may alter treatment compliance, expectancy, and response. Unfortunately, a readily available evidence base to inform clinical practice in this growing population does not exist. We present an algorithm (Figure 1) to help health care providers caring for older adults with CLBP to recognize which patients to screen for dementia and what dementia screening tools to use. The algorithm also highlights clinical considerations regarding pain management in people who may have dementia. To illustrate how to apply the algorithm, we present a case with CLBP and underlying dementia. Ultimately, the purpose of this algorithm is to help detect the presence of cognitive impairment in older patients who report pain so that the provider knows to look for evidence of pain-related suffering rather than rely solely on self-report to develop a pain treatment plan.

Methods

An interdisciplinary panel of eight experts used a modified Delphi technique, described in the CLBP series overview [22], to create an algorithm for the approach to the patient presenting with CLBP and signs of dementia. The clinical indicators of dementia relevant to pain practice were identified through a literature review, with ultimate inclusion decided upon by the consensus of the expert panel. The content expert panel refined the algorithm (Figure 1) and the rationale for the various components of the algorithm (Table 1) based on feedback from a primary care provider panel as part of an iterative process. [22]

Case Presentation

Relevant History

An 87-year-old woman presents with low back pain for seven years. She is two years status post-L2-4 laminectomy after physical therapy and conservative pain management measures failed. She now has persistent pain and difficulty functioning. She is accompanied by her daughters.

The patient is a retired homemaker who used to garden and play tennis in her free time. For the past five years, she has become increasingly sedentary. Fifteen months ago, she moved to an assisted living facility because of difficulty maintaining her two-story home. She still manages her own medications. She reports low back pain on most days, currently 8/10, but cannot describe her pain quality or precipitating factors. She reports pain alleviation with sitting or lying down. She is prescribed tramadol 50 mg two to three times per day as needed but is unable to report how many times she has taken it over the past week. She cannot say whether it is helping her. Her pain worsened during physical therapy, so she stopped going after two or three sessions. Her daughters took over her finances when she moved to assisted living. They also report that the patient had not filled her medications properly for several months prior to moving into the facility and that she had stopped participating in the activities she once relished like gardening, playing Scrabble, and going out to dinner with friends, saying that she no longer enjoyed them.

Relevant Physical Examination

On exam, the patient is neatly dressed and appears comfortable. She has a sad affect and makes poor eye contact. She has mild thoracic kyphosis, no taut bands or trigger points (i.e., no myofascial dysfunction), and full/painless internal hip rotation bilaterally. Her strength is 5/5 in all extremities. Her sensory exam is normal. When asked to walk, she says that she has too much pain to do so. When the examiner offers her hand, she takes it and walks 15 feet without difficulty. When asked to walk farther, she grimaces, begins rubbing her back, and says that she needs to sit down because she is experiencing pain. Because of her advanced age and inability to provide sufficient pain-related detail during the history, a Montreal Cognitive Assessment exam is performed and reveals a score of 21/30.

Clinical Course

Based upon the history and physical examination, the following recommendations are made:1) Neuropsychological testing to evaluate for possible dementia and/or possible depression;

2) discontinue tramadol;

3) begin acetaminophen 1,000 mg by mouth three times per day;

4) collaborate with the assisted living facility director and/or nursing staff to devise a supervised medication administration program to ensure this resident takes scheduled analgesia while retaining some self-efficacy and independence;

5) physical therapy with specific attention to reducing fear avoidance beliefs;

6) request that staff (nursing, aides, direct care workers) at assisted living facility record pain behavior observations, specifically activity engagement, grimacing during ambulation, and pain verbalizations to help track treatment outcomes;

7) activities staff to engage patient in a gardening group.

Approach to Management

As shown in the algorithm (Figure 1), the first step in the approach to this patient is to look for signs of possible dementia, and our patient exhibited several indicators. The patient in the case is 87 years old and presents with a report of refractory back pain. She does not have known dementia. The prevalence of dementia in adults aged 85 and older has been reported to be as high as 50%. [5] Therefore, clinical suspicion, particularly when even very subtle changes in memory, behavior, activity, or performing usual tasks are detected, supports screening for dementia in the oldest old (e.g., age 85 and older). [23, 24] While other guidelines do not recommend routine screening in those age 85 or older because of ineffective pharmacologic and/or nonpharmacologic dementia treatment, we recommend routine screening for those with CLBP because of the profound impact that dementia can have on the experience, expression, and treatment of pain.

A second clinical sign in our case that should lead to dementia screening, as shown in Figure 1, is the dearth of specifics provided during the pain history, with frequent corroboration from an informant when present. In the early stages of dementia, patients are often able to participate in conversation without any obvious indication of cognitive impairment as retained social skills can mask the presence of cognitive deficits. [18] However, underlying dementia may unmask itself as details surrounding the pain history are explored and the patient is unable to provide sufficient information. Cognitive impairment is so common in people 85 and over that providers would be well advised to encourage these patients to bring an advocate or family member who knows them to participate in the appointment. [25] At the same time, patients often defer to informants during the interview to compensate for immediate and remote memory difficulties. Some patients with dementia have the “head-turning sign”; that is, they repeatedly turn to their family member when the examiner asks them a question. [26] Our patient reports severe pain on most days, including at the time of the encounter, and relief with inactivity. She cannot provide additional details about her pain experience, and her daughters fill in the remainder of the pain history, particularly surrounding pain-related disability. [27]

Difficulty with information processing is another sign of dementia. This can be uncovered during the physical examination as an inability to follow complex commands such as the directions for the Timed Up and Go Test that is used commonly to assess fall risk: stand up, walk to the line, turn around, walk back to the chair and sit down. [28] The patient may stand up and walk to the line, then stop and wait for further directions rather than completing the task. Difficulty with information processing makes it hard for a patient to independently participate in a pain management plan and typically requires family or caregiver support to follow through.

Our patient’s withdrawal from daily activities represents another potential clue of an underlying dementia. She reports that she no longer enjoys long-standing hobbies, which she and her daughters attribute to persistent pain. Another pain-related explanation for disengagement from previously enjoyable daily activities could be attributed to maladaptive pain coping, where fear avoidance beliefs lead to disengagement over time. [29] However, decreased engagement in usual activities and hobbies can also be indicative of dementia. [30] Research demonstrates that older adults across the spectrum of cognitive impairments demonstrate greater variability in performance of daily activities and increasing disability as they progress. [31] Impaired cognition can have a significant effect on medication compliance, as well as impact one’s ability to participate in activities secondary to progressive loss of problem-solving skills and memory, which represents another clinical indicator to support a screen for dementia, per Figure 1. It also should be highlighted that such symptoms may be indicative of underlying depression that may be comorbid with dementia.

Our patient was screened for dementia as she exhibited several signs of dementia (listed in Figure 1). The expert interdisciplinary panel evaluated multiple screening tools for dementia and ultimately recommended three based upon their ease of use in the clinical setting, time to complete the measures, and their psychometric properties for accurately identifying dementia (Table 1). The suggested tools include the Mini-Cog, MoCA, and SLUMS. [11–13] The Eight-item Interview to Differentiate Aging and Dementia (AD8) is another brief dementia screening tool that can be administered either to an informant (preferred) or the patient. This instrument differs from the other screening measures in that it queries intra-individual change across a variety of cognitive domains. [32] Our patient completed the MoCA, for which she scored 21/30, indicating a positive screen for dementia (i.e., score < 26).

For patients who screen positive, and for patients who screen negative but for whom a high clinical suspicion of dementia remains, a referral for formal dementia evaluation may be warranted. A formal dementia evaluation starts with a standard clinical assessment for change in cognition, which can be performed either by a primary care provider or by a subspecialty dementia expert such as a neurologist, geriatrician, or geriatric psychiatrist. Reasons to pursue a more comprehensive workup by a subspecialty expert, including comprehensive assessment of cognition and mood by a neuropsychologist, include uncertainty about the diagnosis or type of dementia, early onset, rapid progression, and the need for a clear understanding of a patient’s retained and lost cognitive abilities. [24, 33–35] A negative screen in conjunction with a low index of suspicion for an underlying dementia supports continuing with comprehensive pain evaluation.

Per Figure 1, once a diagnosis of dementia is established, the next step is to determine whether the patient can report pain verbally. The majority of patients in the outpatient setting have retained ability to report pain. If the patient lacks this ability, a nonverbal pain assessment tool should be used to evaluate for pain-related behaviors. Although multiple validated tools are available, no tool is appropriate for every setting and current evidence does not support recommending one tool over another. [36, 37]

One of the most commonly used tools, the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale (PAINAD), can be used to systematically evaluate pain-related behaviors. [38] The PAINAD requires five minutes of observation during activity and incorporates five indicators of discomfort rated on three levels: 0 = absent; 1 = present but not constant or severe; and 2 = severe/constant. The scoring was intended to help delineate pain severity. While the tool can be used to determine the presence or absence of pain behavior, its use to determine severity is not supported. [39] If the evaluation supports the presence of significant pain, then the patient should be evaluated to identify sources of pain so that appropriate treatments can be initiated. When a patient maintains the ability to report pain, similar to our patient, the observation of pain-related behaviors (for example, grimacing and vocalizations), especially during physical activity, should be integrated into the assessment to help validate the reported experience and inform the need for additional interventions.

Next, physical assessment is used to corroborate the patient’s self-report. The patient exhibits reluctance to ambulate during the encounter but can be coaxed to do so with encouragement and support from the provider. Once up, she is able to ambulate a short distance without pain. When asked to ambulate further, she grimaces and braces her back, possibly indicating the presence of pain.

The absence of pain during ambulation, coupled with ongoing report of severe pain, represents inconsistency between patient self-report and pain-related behavior. This real-time patient observation while performing an activity reported to be associated with pain (i.e., if the patient says walking is too painful, observe her while she walks and ask her about her pain at that moment) provides valuable information about the pain history as well as allows comparison of self-reported pain and pain behaviors. The presence of such inconsistency (i.e., “a disconnect”) represents another possible sign of dementia (see Figure 1). Moreover, pain behaviors and attention to pain may be exaggerated in patients with dementia. [40] Our patient appears to demonstrate fear avoidance beliefs with her initial reluctance to ambulate and yet ambulates when holding the hand of the examiner. Fear of pain may have contributed to our patient’s decreased activity level and indicates a sign of maladaptive coping as well. [29] Management of maladaptive coping (e.g., fear-avoidance beliefs, catastrophizing) is addressed in a separate algorithm in this series. [29]

When there are signs of physical or emotional suffering, such as in our patient during continued ambulation, then the source of the suffering must be clarified. If suffering is clearly related to pain, then appropriate pain interventions should be initiated. If suffering does not appear to be related to pain or as in the case of our patient not solely due to pain, then other causes should be sought and managed as well. Social isolation, depression, and fear of pain can all drive pain reporting. Often maladaptive coping with fear avoidance leads to inactivity and social isolation. Depression commonly coexists with pain in older adults and can also lead to withdrawal from activities and social isolation. Assessment of depression is addressed in another algorithm in the series [41]. Social isolation can be relieved with enrollment in a day program or a move to an assisted living facility. We recommended that our patient participate in a gardening group. Our patient exhibited signs of physical pain as well as fear avoidance in her reluctance to ambulate. This fear of causing pain resulted in her withdrawal from activities including previous physical therapy. Her management plan included both an analgesic trial with scheduled acetaminophen, physical therapy with specific attention to reducing fear avoidance beliefs, and participation in a gardening group to encourage a pleasurable activity that included socialization. We wish to highlight that while nursing, physical therapy, and activities therapy were provided on-site for our patient, these resources are not available at many assisted living facilities. For facilities that do not provide nursing care or rehabilitation services, the provider may wish to collaborate with home health for nursing care and physical therapy either through home health or outpatient-based services. Similarly, for engagement in a gardening group without on-site activities therapy, one might consider a nearby senior center or community volunteer organization.

If no sources of suffering are identified, then pain perseveration should be considered as a potential explanation of our patient’s pain report, as indicated in Figure 1. Pain perseveration is the repeated reporting of pain that occurs without any sign of associated distress. Like other forms of perseveration, it occurs despite the absence or cessation of a stimulus and is a common characteristic of dementia. [42] Patients with pain perseveration will not exhibit nonverbal pain behaviors. Pain perseveration becomes the most likely explanation when the family or caregiver reports frequent pain report by a patient who does not appear to be in pain or when a patient who frequently talks about pain during the clinical encounter does not demonstrate objective signs of pain during the evaluation.

An empiric analgesic trial may or may not be helpful in distinguishing physical pain from pain perseveration. [43] Patients with chronic noncancer pain will not become pain-free with treatment. [44] They can be expected to continue to report pain, as can those with pain perseveration. As noted earlier, it is critical to ensure that persistent pain reporting is not associated with suffering before ascribing it to perseveration and to note whether the persistence of pain reporting indicates lack of analgesic efficacy. Thus an analgesic trial must be coupled with the other assessment approaches described in this paper. When pain perseveration is suspected to be the driver of pain reporting, the best intervention may be distraction, a strategy that can have analgesic benefits as well. [45] Another strategy providers and caregivers can use to manage patients with pain perseveration is to avoid asking about pain unless nonverbal indicators or other signs of pain-related suffering emerge.

Resolution of Case

Three months later, the patient and her daughters return for follow-up. Neuropsychological testing confirms a diagnosis of dementia secondary to probable Alzheimer’s disease. The patient continues to benefit from acetaminophen 1,000 mg three times a day. Her supervised medication administration program ensured that she took the acetaminophen regularly, and that seemed to help increase participation in physical therapy. The physical therapy program was recently completed, and the patient is now able to walk at least 20 minutes at a time on most days of the week. The patients’ daughters and staff have learned to avoid initiating conversations about pain, particularly in the absence of signs of suffering. Both daughters report rare spontaneous complaints of back pain when they visit. They have observed their mother to be much more animated, and they recently attended the assisted living’s annual garden show that featured a display their mother had helped to create. The pain logs indicate that the assisted living staff has observed much less frequent pain reporting and pain behaviors.

Summary

Recognizing that the older adult with CLBP also has dementia can substantively shape the approach to pain management. Dementia impacts multiple aspects of pain evaluation and management, including pain reporting, treatment compliance, pain coping, treatment expectancy, and treatment response. The dearth of literature on nonpharmacological approaches to chronic pain treatment in those with dementia underscores the need for a rational clinical approach to this common conundrum. The approach outlined here has been informed by the clinical experience and expertise of geriatricians.

Dementia often goes unrecognized by many practitioners, resulting in overly pain-focused treatment. Chronic pain cannot be eradicated [44], but it can be managed. Patients with chronic pain always will have pain on which they can report. The job of the provider evaluating the older patient with a pain complaint is to identify whether the pain itself should be the focus of treatment (i.e., evidence that the patient is suffering from pain), whether dementia and dementia-related behaviors should be the focus of treatment, and whether both pain and dementia require intervention. This approach truly reflects patient-centered care.

Key Points

Dementia impacts pain reporting (especially historical details), treatment compliance, pain coping, treatment expectancy, and treatment response.

Older adults with CLBP should be screened for dementia when:

They’re older than age 85 years.

They have difficulty providing logical details during the history.

There is self- or caregiver report of observed memory or functional decline.

There is observed difficulty with information processing during the history and/or physical examination.

There is discrepancy between self-reported pain/pain interference and observed pain interference in real time.

Pain report should not be equated automatically with pain-related suffering. Other causes of pain report may include perseveration, pain-related fear, or a substitute for other unmet needs. Ascertaining the cause will profoundly impact management.

Pain self-management in the older adult with dementia should involve the caregiver(s). When referring the older adult with CLBP and dementia for treatment (e.g., physical therapy), always encourage the caregiver to attend as a way to optimize compliance.

Funding sources:

This material is based on work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service.

Disclosure and conflicts of interests:

The contents of this report do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. The authors report no conflicts of interests.

References:

Shega J, Tiedt A, Grant K, Dale W. Pain measurement in the national social life, health, and aging project: Presence, intensity, and location. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Sociol Sci 2014;69(2):191–7

Shega J, Emanuel L, Vargish L, et al. Pain in persons with dementia: Complex, common, and challenging. J Pain 2007;8(5):837–8

Persons AGSPoCPiO. The management of persistent pain in older persons: AGS panel on persistent pain in older persons. J Amer Geriatr Soc 2002;6(50):205–24

Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, et al. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. JAMA 1998;279(23):1877–82

Hugo J, Ganguli J. Dementia and cognitive impairment: Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Geriatr Med 2014;30(3):421–42

Connolly A, Gaehl E, Martin H, Morris J, Purandare N. Underdiagnosis of dementia in primary care: Variations in the observed prevalence and comparisons to the expected prevalence. Aging Ment Health 2011;15(2):978–84

Gatchel R, Peng Y, Peters M, Fuchs P, Turk D. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull 2007;133(4):581–624

Porter F, Malhotra K, Wolf C, et al. Dementia and response to pain in the elderly. Pain 1196;68(2–3): 413–21

Kunz M, Scharmann S, Hemmeter U, Schepelmann K, Lautenbacher S. The facial expression of pain in patients with dementia. Pain 2007;133(1–3):221–8

Cole L, Farrell M, Duff E, et al. Pain sensitivity and fMRI pain-related brain activity in Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2006;129(Pt 11):2957–65

Borson S, Scanlan J, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: Validation in a population-based sample. J Amer Geriatr Soc 2003;51(10):1451–4

Nasreddine Z, Phillips N, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Amer Geriatr Soc 2005;53(4):695–9

Tariq S, Tumosa N, Chibnall J, Perry M, Morley J. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the mini-mental state examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder: A pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;114(11):900–10

Achterberg W, Pieper M, van Dalen-Kok A, et al. Pain management in patients with dementia. Clin Interv Aging 2013;8:1471–82

Shega J, Andrew M, Hemmerich J, et al. The relationship of pain and cognitive impairment with social vulnerability—an analysis of the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Pain Med 2012;13(2): 190–7

Hunt L, Covinsky J, Yaffe K, et al. Pain in community-dwelling older adults with dementia: Results from the national health and aging trends study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63(8):1503–11

Shega J, Ersek M, Herr K, et al. The multidimensional experience of noncancer pain: Does cognitive status matter? Pain Med 2010;11(11): 1680–7

Weiner D, Peterson B, Logue P, Keefe F. Predictors of pain self-report in nursing home residents. Aging 1998;10(5):411–20

Sampson E, White N, Lord K, et al. Pain, agitation, behavioural problems in people with dementia admitted to general hospital wards: A longitudinal cohort study. Pain 2015;156(4):675–83

Husebo B, Ballard C, Sandvik R, Nilsen O, Aarsland D. Efficacy of treating pain to reduce behavioural disturbances in residents of nursing homes with dementia: Cluster randomised control trial. BMJ 2011;343:d4065.

Herr K, Coyne P, McCaffery M, Manworren R, Merkel S. Pain assessment in the nonverbal patient: Position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Manag Nurs 2011;12(4):230–50

Weiner DK.

Deconstructing Chronic Low Back Pain in the Older Adult -

Shifting the Paradigm from the Spine to the Person

Pain Med 2015; 16 (5): 881–885Valcour VG, Masaki KH, Curb JD, Blanchette PL. The detection of dementia in the primary care setting. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2964–8

Galvin JE, Sadowsky CH. Practical guidelines for the recognition and diagnosis of dementia. J Am Board Fam Med 2012;25:367–82

McCarten JR. Clinical evaluation of early cognitive symptoms. Clin Geriatr Med 2013;29:791–807

Fukui T, Yamazaki T, Kinno R. Can the ?head-turning sign? be a clinical marker of alzheimer's disease? Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2011;1:310–7

Murray T, Sachs G, Stocking C, Shega J. The symptom experience of community-dwelling persons with dementia: Self and caregiver report and comparison with standardized symptom assessment measures. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;20(4):298–305

Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The Timed “up and go”: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr 1991;39:142–8

DiNapoli EA, Craine M, Dougherty P, et al.

Deconstructing Chronic Low Back Pain in the Older Adult - Step by Step

Evidence and Expert-Based Recommendations for Evaluation and Treatment.

Part V: Maladaptive Coping

Pain Medicine 2016 (Jan); 17 (1): 64–73McKhann G, Knopman D, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7(3):263–9

Rodakowski J, Skidmore E, Reynolds C, et al. Can performance of daily activities discriminate between older adults with normal cognitive function and those with Mild Cognitive Impairment? J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1347–52

Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, et al. The AD8: A brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology 2005;65(4):559–64

Simmons BB, Hartmann B, Dejoseph D. Evaluation of suspected dementia. Am Fam Physician 2011;84: 895–902

Schmand B, Tiesntra A, Tamminga H, et al. Responsiveness of magnetic resonance imaging and neuropsychological assessment in memory clinic patients. J Alzheimers Dis 2014;40:409–18

Gauthier S, Patterson C, Chertkow H, et al. Recommendations of the 4th Canadian Concensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia (CCCDTD4). Can Geriatr J 2012;15: 120–6

Corbett A, Husebo B, Malcangio M. Assessment and treatment of pain in people with dementia. Nat Rev Neurol 2012;8(5):264–74

Lichtner V, Dowding D, Esterhoizen P. Pain assessment for people with dementia: A systematic review of systematic reviews of pain assessment tools. BMC Geriatrics 2014;14:138

Warden V, Hurley A, Volicer L. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2003;4(1):9–15

Zwakhalen SM, van der Steen JT, Najim MD. Which score most likely represents pain on the observational PAINAD pain scale for patients with dementia? J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13(4):384–9

Shega J, Rudy T, Keefe F, et al. Validity of pain behaviors in persons with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56(9):1631–7

Carley JA, Karp JF, Gentili A, et al.

Deconstructing Chronic Low Back Pain in the Older Adult - Step by Step

Evidence and Expert-Based Recommendations for Evaluation and Treatment.

Part IV: Depression

Pain Medicine 2015 (Nov); 16 (11): 2098–2108Seidel G, Giovannetti T, Libon D. Cerebrovascular disease and cognition in older adults In: Pardon MC, Bondi M, editors. , eds. Behavioral Neurobiology in Aging. New York: Springer; 2012:213–42

Malec M, Shega J. Pain management in the elderly. Med Clin North Am 2015;99(2):337–50

Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole MR.

Clinical Importance of Changes in Chronic Pain Intensity

Measured on an 11-point Numerical Pain Rating Scale

Pain 2001 (Nov); 94 (2): 149-158Buhle JT, Stevens BL, Friedman JJ, Wager TD. Distraction and placebo: Two separate routes to pain control. Psychol Sci 2012;23(3):246–53

Shega J, Rudy T, Keefe F, et al. Discriminate validity of pain behaviors in persons with mild to moderate cognitive impairment. J Amer Geriatr Soc 2008;56(9):1631–7

Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, Vitaliano P, Dokmak A. The Mini-Cog: A cognitive ?vital signs? measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000;15(11):1021–7

Banks W, Morley J. Memories are made of this: Recent advances in understanding cognitive impairment and dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003;58(4):314–21

Fage BA, Chan SH, Gill SS, et al. Mini-Cog for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias in a community setting. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;2: CD010860

Pautex S, Michon A, Guedira M, et al. Pain in severe dementia: Self-assessment or observational scales? J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1040–5.

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Since 8-30-2016

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |