Which Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Patients Will Improve

with Nonsurgical Treatment? A Aecondary Analysis

of a Randomized Controlled TrialThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2025 (Dec 9); 33: 57 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Eric J Roseen Clair N Smith Asifa Rahim Conor Deal

Ryan Fischer Natalia E Morone Andrew Flack, et al.

Section of General Internal Medicine,

Department of Medicine,

Boston University Chobanian and Avedisian School of Medicine

and Boston Medical Center,

Boston, MA, USA.

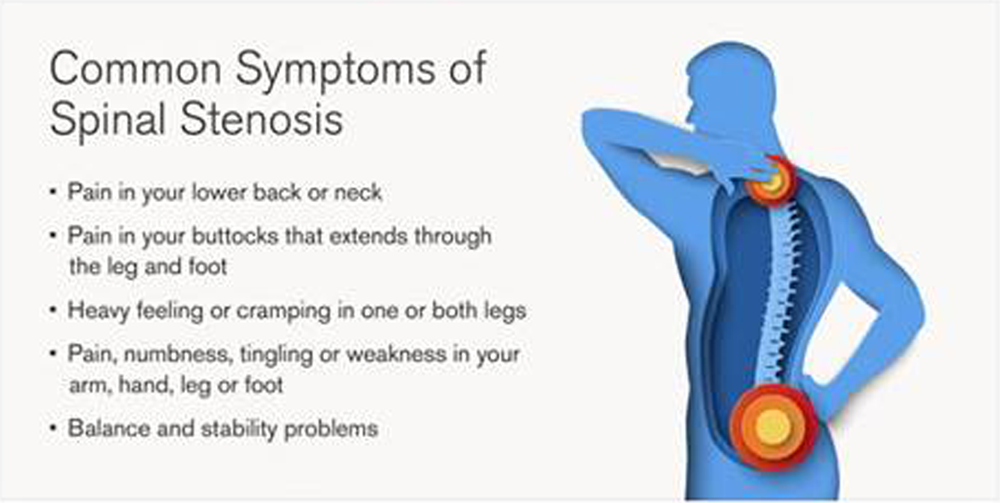

Background: Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) can be disabling and is a leading reason for spinal surgery in older adults. While nonsurgical treatments are recommended as first-line treatment, it remains unclear which patients will benefit most.

Purpose: To identify patient characteristics associated with larger improvements or larger treatment effects among adults receiving nonsurgical LSS interventions.

Design: Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Outpatient research clinics.

Subjects: 216 older adults with symptomatic LSS.

Methods: Participants, recruited from November 2013 to June 2016, were randomized to receive:(1) manual therapy with an individualized exercise program (MTE);

(2) a group exercise program (GE); or

(3) medical care (MC).We evaluated the association of baseline characteristics with 2-month change in primary outcomes: symptoms and function on the Swiss Spinal Stenosis questionnaire (SSSQ); and walking capacity in meters (m) on the self-paced walking test (SPWT). Baseline characteristics included sociodemographic and clinical variables. To explore heterogeneity of treatment effects, we evaluated unadjusted stratified estimates when comparing MTE to GE/MC. Additionally, we included an interaction term in models to test for statistical interaction.

Results: At baseline, participants (mean age = 72, 54% female, 23% non-white) had moderate LSS-related symptoms/impairment (mean SSSQ score = 31.3) and limited walking capacity on SPWT (mean = 451 m). The overall improvement on SSSQ was 2.5 points with larger improvements observed among younger, non-white, non-smoking participants, and those with worse baseline LSS or back-related symptoms/impairment. Overall improvement on the SPWT was 205 m with larger improvements observed among younger participants, those with higher baseline physical activity levels and participants without knee osteoarthritis. For SSSQ, the treatment effect was larger among adults aged < 70 versus older adults (MTE vs. GE/MC; mean difference [MD] = - 4.06, 95% CI = - 6.29 to - 1.83 vs. MD = - 0.47. 95% CI = - 2.63 to 1.69, respectively; p-for-interaction = 0.02). For walking capacity, the treatment effect was larger among adults with hip osteoarthritis compared to those without (MTE vs. GE/MC; MD = 500 m, 95% CI = 71 to 929, vs MD = 13 m, 95% CI = - 120 to 147, respectively; p-for-interaction = 0.007).

Conclusions: In a sample receiving nonsurgical treatments for LSS, we identified patient-level characteristics associated with larger improvements and/or treatment effects. If confirmed in larger randomized controlled trials, these findings may guide clinical decision-making to enhance clinical outcomes.

Gov identifier: ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT01943435

Keywords: Chronic pain; Group exercise; Nonpharmacologic treatment; Older adults; Primary care; Spinal stenosis; Walking.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is a highly prevalent and disabling cause of low back and leg pain in older adults, typically characterized by worsening symptoms with lumbar extension and improved symptoms with lumbar flexion. [14] Adults with LSS often do not meet guidelines for physical activity due to persistent back and leg symptoms that limit walking and other daily activities, putting them at risk of functional decline and early mortality. [57]

Furthermore, LSS is the most common reason for elective surgery in adults over the age of 65, contributing to high healthcare costs for those afflicted. [8, 9] Patients typically experience relief immediately following surgery, but often regress to their previous pain levels in long-term follow-up. [1012]

Surgery carries inherent risks and may not be suitable for all patients, particularly those who have not exhausted nonsurgical treatment options. [13] Thus, a stepped approach to care beginning with nonsurgical treatment is recommended in clinical practice guidelines, with several nonsurgical treatments being considered safe and effective for LSS. [14, 15] Determining who could benefit most from nonsurgical treatment would help guide care, avoid unnecessary surgery, and reduce healthcare costs.

Predictors of improvement (i.e., prognostic factors) have been described for older adults with LSS undergoing surgery, e.g., higher walking capacity and the absence of psychological factors before surgery are associated with better post-surgical outcome measures such as self-reported symptom severity or walking capacity. [1618] However, few studies have evaluated predictors of improvement in nonsurgical cohorts. Prior studies have noted that walking capacity [16, 19] and psychosocial factors [20, 21] may also predict outcomes in nonsurgical LSS populations. Several patient characteristics that contribute to LSS development may be important prognostic factors, e.g., older age, obesity, smoking. [22, 23] However, it remains unclear if these factors predict LSS outcomes independent of treatment. Our study will evaluate whether there are predictors of improvement among patients receiving non surgical approaches for LSS.

Heterogeneity of treatment effects (i.e., treatment effect modification) by baseline characteristics has the potential to guide treatment selection. [2426] Indeed, identifying tangible patient characteristics that delineate subgroups of patients that are expected to have larger or smaller treatment effects is a longstanding priority for low back pain research agendas. [27, 28] However, these analyses are challenging as they are ideally performed using data from a large randomized controlled trial with measurement of potential effect modifiers prior to treatment allocation. [29] Given that LSS is a unique patient population with different clinical outcomes, such as stenosis-related symptoms or function and walking capacity, additional studies are needed to identify treatment effect modifiers of LSS treatments. To our knowledge, no prior studies have evaluated effect modification when comparing nonpharmacologic treatments. Addressing this gap in current literature is important in identifying which patients are most likely to benefit from a clinician-delivered treatment such as manual therapy and individualized exercise compared to less-intensive approaches such as general exercise programs or usual medical care. Thus, our study will also evaluate whether there are treatment effect modifiers of a manual therapy and exercise intervention when compared to other nonsurgical approaches for LSS.

A randomized controlled trial by Schneider et al., reported that a combination of manual therapy and an individualized exercise program provides greater short-term improvement in stenosis-related symptoms and physical function and walking capacity than medical care or a group exercise program. [30, 31] We performed secondary analyses of the data from this trial to explore two additional important clinical questions:First, what pre-treatment patient characteristics may be important predictors of improvement in a nonsurgical LSS patient population?

Second, which pre-treatment patient characteristics potentially explain heterogeneity of treatment effects when comparing manual therapy and individualized exercise to medical care or a group exercise program?

Methods

Design

This is a secondary analysis of a three-arm RCT with details on study design and main outcomes reported elsewhere [30, 31]. A total of 259 participants with symptomatic LSS were randomized to one of the following three intervention groups: (1) manual therapy and individualized exercise; (2) group exercise; and (3) medical care. For analyses in this manuscript evaluating treatment effects, we collapsed group exercise and medical care groups into a single comparison group, i.e., to compare manual therapy and individualized exercise to other nonsurgical treatment options. All interventions were delivered over a 6-week period with the current analyses focusing on short-term follow-up, i.e., primary outcomes at the 2-month endpoint. We included 216 (83%) participants with complete 2-month outcome data in these analyses. [31] Participant recruitment and follow-up occurred from November 2013 to June 2016.

Participants

Adults over the age of 60 years with LSS were eligible if they had evidence of central and/or lateral canal stenosis on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) and clinical symptoms associated with LSS (neurogenic claudication; less symptoms with flexion).

Interventions

Manual therapy and individualized exercise (MTE) This intervention group involved twice-weekly sessions for 6 weeks (12 total sessions) with participants assigned to either a chiropractor or physical therapist. These clinicians delivered a standardized protocol including a warm-up on an exercise bike, manual therapy techniques (mobilization of spine, hips, muscles, nerves and other surrounding soft tissues), and personalized stretching and strengthening exercises based on individual needs. This intervention was aimed at managing symptoms by improving mobility of the lower back and hip joints, nerves and muscles. [3133]

Group exercise (GE)

This intervention group participated in twice-weekly supervised exercise classes for older adults for 6 weeks (12 total sessions). The group exercise classes were 45 min in length and led by certified exercise instructors. Participants were allowed to self-select between easy and medium intensity exercise classes. This intervention was aimed at improving overall physical fitness with general exercises in a group setting (non-individualized).

Medical care (MC)

This intervention group received a 6-week pain management program delivered by a physiatrist. Participants initially received a combination of first-line prescribed oral medications (non-narcotic analgesics, anticonvulsants, or antidepressants) tailored to their specific needs. The physiatrist provided participants with general recommendations for gentle stretching and advice to stay active, to complement the medication management plan. If oral medications provided inadequate pain relief, participants were offered epidural steroid injections as a second-line treatment option. The decision to receive injections (which occurred in 20% of participants) also involved shared decision-making, considering factors like patient preference and neurogenic claudication severity. This intervention aimed to improve pain management through individualized medication, basic lifestyle modifications, and optional injections.

MeasuresPrimary outcomes

Consistent with the original trial, our pre-specified primary outcomes were symptom severity and function on the Swiss Spinal Stenosis Questionnaire (SSSQ) and walking capacity on the self-paced walking test (SPWT). [30, 31] We used the SSSQ total score, which was calculated by combining the symptom domain sub-score (7-items, scores range: 735) with the function domain sub-score (5-items, scores range: 520). [30, 31] Thus, SSSQ total scores can range from 12 to 55 with higher scores indicating worse symptom severity and more impaired function. [3437] Walking capacity on the SPWT was the distance in meters (m) walked before stopping due to symptoms with a maximum duration of 30 min. [38, 39]

Baseline characteristics

To identify relevant baseline characteristics, we performed a literature review in a single database (i.e., PubMed) to identify studies that evaluated:(1) potential predictors of LSS outcomes using validated questionnaires (e.g., SSSQ) or an objective measure of walking capacity; and/or

(2) treatment effect modifiers in LSS intervention trials that measured these outcomes.Additional details and findings from this review are shown in Supplemental file 1 (Appendix Tables 14). Given a limited number of prior studies, novel baseline characteristics (i.e., those not evaluated in previous studies) were included if there was consensus from the research team that the characteristic could theoretically influence prognosis or treatment effects. The team includes researchers and clinicians who have previously applied relevant theoretical frameworks such as the WHOs International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework and the biopsychosocial model in older adults with pain conditions. [18, 40] To form clinically-meaningful subgroups we used established clinical cut points when available, e.g., to define obesity and severe back-related disability on the Oswestry Disability Index. [41] If established cut points were not available for continuous measures (e.g., age, baseline physical activity levels), we selected a cut point value near the median value to allow for more stable strata-specific estimates.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics included age (<70,≥70 years), sex (male, female), race (white, nonwhite), marital status (married, not married), and household income (<$40,000/year,≥$40,000/year).

Clinical characteristics

General health characteristics included obesity (≤30,>30 Body Mass Index) and smoking status (never, prior/current smoker). The number of comorbid health conditions (≤4,>4) was identified from the Modified Comorbidity Disease Index. The presence of co-occurring hip or knee osteoarthritis (yes, no) were evaluated on physical examination using clinical criteria from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). [42, 43] Participants were administered an ankle-brachial index test, a measure used to indicate the presence of peripheral artery disease that may cause leg pain, with lower values indicating more narrowing or blockage of lower extremity arteries (<1,≥1 indicating those with or without vascular claudication). We also included clinically important thresholds for baseline gait speed (<1 m/s,≥1 m/s), meters walked in a self-paced walking test (<280 m,≥28 0 m), and amount of physical activity (<165 min/day,≥165 min/ day) measured by accelerometer data averaged over one week (SenseWear; BodyMedia Inc).

Back-related variables included back and leg symptom duration (≤6,>6 month), and back/leg pain intensity (≤6,>6) on the 010 numerical rating scale. Imaging interpretation from prior MRI or CT reports were reviewed to identify the presence (yes/no) of central canal stenosis, lateral recess stenosis, and intervertebral foramen stenosis. [31] From these, we characterized participants as having lateral canal stenosis only (lateral recess or intervetebral foramen), central canal stenosis only, or both central and lateral canal stenosis. We used the Oswestry Disability Index to define mild to moderate back-related disability versus severe disability (≤40 and>40, respectively). [41] The median total SSSQ score (>31) was also used. We identified individuals with at least mild depressive symptoms on the short-form version of the PROMIS depression scale (t-score≥55). [44]

We identified individuals with higher levels of kinesiophobia using the median value of≥26 for the 11-item shortform of the Tampa Kinesiophobia Scale; which has scores from 11 to 44 with higher scores indicating worse kinesophobia. [45] Participants were asked about their expectations of each of the interventions prior to randomization using a 5-item pain-specific expectations questionnaire; potential scores range from 9 to 54 with higher scores indicating more favorable expectations. [46] We used responses specific to MTE, and identified those who were above the median score of 43, with scores above this value indicating favorable expectations for MTE.

Data analysis

Baseline characteristics across the three treatment groups were summarized using means (SD) for continuous variables and frequencies (%) for categorical variables.

We took a descriptive approach to evaluating predictors of improvement and heterogeneity of treatment effects. [47] This approach emphasizes stratum-specific changes or effect estimates, and not just the results of statistical tests, i.e., we focus primarily on direction and magnitude of change or effect estimate and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), although 95% CIs are based on a p-value of 0.05. [47] Thus, analyses were considered to be exploratory and hypothesis generating. For predictors this meant evaluating the magnitude of the within- and between- stratum changes in outcomes (e.g., changes in outcomes among all male or female participants). For treatment effect modification, this meant evaluating the magnitude of treatment effects within each stratum of baseline characteristics (e.g., treatment effect when comparing MTE to GE/MC among all male or female participants).

We evaluated predictors of improvement using our primary outcomes, changes in stenosis-related symptoms and physical function on the SSSQ and walking capacity on the SPWT. We calculated the mean change scores for each measure from baseline to the 2-month endpoint. We report the overall change score (i.e., among all participants) and change scores for each stratum of the baseline characteristics (i.e., among subgroups). Additionally, we calculated the between strata differences and their 95% confidence intervals to assess associations between baseline characteristics and changes in outcomes at 2 months. Forest plots were used to illustrate stratumspecific estimates of change with their 95% confidence intervals stratified by baseline characteristics.

We evaluated treatment effect modification using the specific contrast of manual therapy and individual exercise compared to all other participants, i.e., combining participants who received group exercise or medical care into one comparison group. To explore heterogeneity, we calculated the overall 2-month treatment effect (i.e., all participants) and treatment effects in each stratum of the baseline characteristics (i.e., within subgroups). Forest plots were used to illustrate stratumspecific 2-month treatment effect estimates with their 95% confidence intervals stratified by baseline characteristics. Statistical interaction was assessed with linear regression models that included effects for the potential moderator, the treatment group, and an interaction term (moderator*treatment group). Statistically significant interaction terms (p<0.05) were considered evidence of potential effect modification while a p-value of 0.05 to 0.20 indicated exploratory evidence for potential effect modification. [25, 26]

To aid interpretation of the magnitude of changes, we identified a range of values indicating a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for each scale. [48] MCIDs for improvements in stenosis-related symptoms and physical function on the SSSQ calculated previously from our sample using multiple approaches ranged from 4.2 to 5.5 points. [36] MCIDs for improvements in walking capacity on the SPWT from multiple prior studies ranged from 319 to 376 m. [36, 49, 50] We identified strata (i.e., subgroups) where the overall or within-group average improvement (i.e., changes within the MTE, GE, or MC groups) met some or all of the pre-specified thresholds, i.e. scores within or above the MCID range, respectively.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1

page 5

Figure 1

page 6Among 216 participants with 2-month outcome data, 75 received manual therapy and individualized exercise, 65 received group exercise, and 76 received medical care. Participant characteristics (mean age=72, 54% female, 23% non-white), are presented in Table 1. Participants reported moderate stenosis symptoms and functional impairment (mean SSSQ score=31.3) and limited walking capacity (mean=451 m) at baseline.

Predictors of change

Overall and stratified changes in stenosis-related symptoms and physical function on the SSSQ are shown in Figure 1 and Appendix Table 5 . The overall improvement on SSSQ was 2.5 points with larger improvements observed among younger adults (age<70 vs.≥70 years, 3.2±5.7 vs. 2.0±5.6, MD=1.1, 95% CI=0.37 to 2.70), those self-reporting non-white race (vs. white race, 3.8±5.1 vs. 2.1±5.7, MD=1.73, 95% CI=3.51 to 0.05), and those with higher symptom severity and physical function burden at baseline on the SSSQ (>31 vs.≤31, 4.2±5.4 vs. 0.9±5.3, MD=3.27, 95% CI=4.72 to 1.82) or the Oswestry Disability Index (≥40 vs.≤40, 3.4±5.7 vs. 1.9±5.5, MD=1.48, 95% CI=3.00 to 0.05).

Individuals who had higher expectations for MTE prior to randomization reported larger improvements on SSSQ compared to those with lower expectations using a pain-specific expectations questionnaire (>42 vs.≤42, 3.1±5.7 vs. 1.7±5.5, MD=1.49 (3.02 to 0.05). Smokers had smaller SSSQ improvements (vs. never-smokers, 1.9±5.8 vs. 3.5±5.3, MD=1.60, 95% CI=0.07 to 3.14). Only one stratum-specific 2-month change was within the MCID range for SSSQ of 4.2 to 5.5 points (i.e., baseline SSSQ score>31, 4.2±5.4), and no values were above this range.

Figure 2

page 8Overall and stratified changes in walking capacity on SPWT are shown in Figure 2 and Appendix Table 6. The overall improvement on walking capacity was 205 m with larger improvements observed among younger adults (age<70 vs.≥70 years, 283±511 vs. 138±427, MD=146 m, 95% CI=20 to 271), those without knee osteoarthritis (no knee osteoarthritis vs. osteoarthritis, 247±508 vs. 114±371, MD=133 m, 95% CI=12 to 254), and individuals with higher baseline physical activity levels (≥165 min/day vs.<165 min/day, 295±512 vs. 146±431, MD=148 m, 95% CI=20 to 277). Improvements in walking capacity were smaller among those with higher back-related disability on the Oswestry Disability Index (≥40 vs.≤40, 127±381 vs. 258±521, MD=131 m, 95% CI=252 to 11). No stratum-specific 2-month changes were within or above the MCID range for the self-paced walking test (i.e., 319 to 376 m).

Potential treatment effect modifiers

Figure 3

page 8Overall and stratified treatment effects on SSSQ, when comparing MTE to GE/MC, are shown in Figure 3 and Appendix Table 7. The treatment effect on SSSQ, when comparing MTE to GE/MC, was larger among adults aged<70 versus older adults (MD=4.06, 95% CI=6.29 to 1.83, vs. MD=0.47. 95% CI=2.63 to 1.69, respectively; p-for-interaction=0.02. As shown in Appendix Table 7, four additional characteristics were under the exploratory threshold for statistical interaction: larger effect estimates were observed among individuals with longer duration of back pain symptoms (p-for-interaction=0.09), individuals with at least mild depression (p-for-interaction=0.10), lower baseline physical activity levels (p-for-interaction=0.12), and higher expectations that MTE would be helpful (p-forinteraction=0.17).

As shown in Appendix Table 7, stratum-specific 2-month changes within the MTE group fell within the MCID range for SSSQ (4.2-to-5.5-point improvement) were participants reporting female sex, not married, income<$40,000/year, BMI>30, back symptoms>6 months, lateral canal stenosis only on imaging, hip osteoarthritis on ACR criteria,>4 comorbidities, lower baseline walking capacity, and lower baseline physical activity levels. Larger within-group MTE changes (i.e.,>5.5 points) were observed among adults aged<70 years (5.8±5.7), non-white adults (5.9±4.9), those with baseline SSSQ score above 31 (5.6±6.1), those with baseline leg pain scores rated as>6 on the 010 numerical rating scale (5.5±7.1), and those with at least mild depressive symptoms (7.5±6.1). None of the stratum-specific 2-month within-group changes for GE or MC were within or above the MCID range for SSSQ.

Figure 4

page 10Overall and stratified treatment effects on walking capacity, when comparing MTE to GE/MC, are shown in Figure 4 and Appendix Table 8. For walking capacity, the treatment effect was larger among adults with hip osteoarthritis compared to those without (MD=500, 95% CI=71 to 929, vs. MD=13, 95% CI=120 to 147, respectively; p-for-interaction=0.01). As shown in Appendix Table 8, five additional characteristics were under the exploratory threshold for statistical interaction; larger effect estimates were observed among participants reporting younger age (<70 years, p-forinteraction=0.07), female sex (p-for-interaction=0.11), white race participants (p-for-interaction=0.17), a longer duration of back pain symptoms (p-for-interaction=0.17), and those with higher expectations that MTE would be helpful (p-for-interaction=0.14).

As shown in Appendix Table 8, several stratum-specific 2-month changes within the MTE group were within the MCID range for the self-paced walking test of 319 to 376 m, including participants who at baseline had a BMI≤30, no knee osteoarthritis using ACR criteria, SSSQ of 31 or less, ODI of 40 or less, gate speed≥1 m/s; and measured physical activity of<165 min per day. Larger withingroup MTE changes (i.e.,>376 m) were observed for adults aged<70 years (429±616 m) and those with hip osteoarthritis using the ACR criteria (608±693 m). While none of the stratum-specific 2-month within-group changes for GE or MC were above the MCID range for SPWT, some characteristics were within the range for GE (male sex, non-white race, a duration of back symptoms of 6 months or less) and MC (duration of back symptoms of 6 months or less).

Discussion

Among older adults with lumbar spinal stenosis receiving nonsurgical treatments, several baseline characteristics were associated with 2-month changes in stenosis-related symptoms, function, and walking capacity. Greater improvements in stenosis related symptoms and function were identified among younger, nonwhite, and non-smoking participants, and those with worse back-related disability on the Oswestry Disability Index or higher symptom and function burden on the SSSQ. Improvements in walking capacity were also larger among younger participants, participants without knee osteoarthritis and those with higher baseline physical activity levels. Modest improvements with MTE when compared to the other interventions were relatively consistent across subgroups. However, treatment effects on SSSQ and walking capacity were potentially modified by age group and hip osteoarthritis, respectively. In other words, a large effect of MTE on SSSQ, compared to the other intervention groups, was observed among adults under the age of 70; and no treatment effect on stenosisrelated symptoms and function was observed for adults over the age of 70. Similarly, the effect of MTE on walking capacity when compared to the other intervention groups was large among adults with hip osteoarthritis identified on physical exam using the ACR clinical criteria, and no treatment effect was observed on walking capacity for adults without hip osteoarthritis.

While a large number of studies have looked at prognostic factors in surgical populations [16], relatively few have evaluated predictors of stenosis-specific self-report outcome measures such as the SSSQ or objective measures of walking capacity. Findings from studies with these outcomes in populations receiving surgical interventions or procedures (e.g., spinal injections [51]) are mixed but generally support our findings of better outcomes with younger age, longer duration of pain, and more severe symptoms and worse function at baseline. [18, 5156] While prior observational studies of pain conditions have identified Black race or Hispanic ethnicity as being associated with worse outcomes and less treatment, [57] we found non-white participants had better SSSQ outcomes compared to white participants. While we did not have information to fully explore this association, we suspect barriers to treatment observed in real world settings may be addressed, at least in part, in the context of a clinical trial where everyone is offered treatment. Our findings are also similar to two prior studies of prognostic factors in populations receiving nonpharmacologic treatments, where younger individuals and those with fewer comorbid conditions had better outcomes. [58, 59]

We found that depressive symptoms were associated with changes in SSSQ total score but not walking capacity, which is consistent with prior reviews. [20, 21] However, we found that individuals with depressive symptoms had a better prognosis (i.e., larger shortterm improvements in SSSQ) which is in contrast with prior studies that have found higher baseline depressive symptoms are associated with higher rates of persistent pain in surgical populations. [20, 21] Prior qualitative studies suggest the physical and psychosocial impacts of neurogenic claudication negatively impact outcomes of adults with LSS receiving nonpharmacologic treatments. [37]

We are unaware of other studies of potential treatment effect modifiers for nonpharmacologic treatments for LSS. Thus, our findings should be considered exploratory and hypothesis generating. For example, our findings raise the question of whether the MTE intervention can improve objective walking capacity more than other nonsurgical treatments among individuals with LSS and comorbid hip osteoarthritis. While this finding should be interpreted with caution, particularly given the relatively small number of adults with hip osteoarthritis, it is worth further study. It is important to recognize that hip osteoarthritis itself can mimic symptoms of neurogenic claudication and that hip osteoarthritis and LSS are commonly comorbid. [60, 61] Participants in the original trial were ascribed a diagnosis of hip osteoarthritis based upon physical exam using ACR clinical criteria and X-rays were not performed. [43]

It is possible, therefore, that diminished hip range of motion was caused as much by periarticular soft tissue restrictions as by pathology within the joint (i.e., degenerative disease). And, since manual therapy to the hips and associated soft tissue was part of the MTE intervention, improved walking capacity may have been related to improved hip mobility. In contrast, we did not see similar larger improvements with MTE among participants with knee osteoarthritis, perhaps because our protocol did not involve treatment of the knee. Older adults often have more than one pain condition [40], and may benefit more from treatment that is directed to all body regions that contribute to important outcomes such as walking capacity. [62]

Our study had several limitations. First, we had a relatively small sample size, particularly for treatment effect modification analyses where sample size is ideally>500 participants. [29] Second, we took a descriptive epidemiologic approach which has inherent strengths and weaknesses. [47] This approach involved stratifying changes in outcomes, and treatment effects, by baseline characteristics to identify larger than average changes or treatment effects. We presented the unadjusted values of association that have predictive value but may not have a causal interpretation. Inclusion of baseline characteristics in each analysis was guided by available theory and clinical experience of the research team. However, stratifying by many covariates runs the risk of identifying spurious associations. [24, 47]

Our approach also did not allow us to stratify across multiple baseline characteristics simultaneously, which may add prognostic value. Since further stratification would result in an unmanageable number of strata, predictive models may be used to generate a risk score and to estimate changes or treatment effects within strata of that risk score. [24] The use of two samples and cross-validation is recommended when taking this approach. [24, 63]

Despite the above limitations, our study also had several strengths. Our study is the first to evaluate whether there are effect modifiers of a manual therapy and exercise intervention compared to other nonsurgical approaches for LSS. By evaluating single factors, our findings should be feasible to replicate and, if they are replicated, relatively simple to implement in clinical practice. Additional studies could be combined with ours through meta-analysis to provide estimates with narrower confidence intervals. This is in contrast with prior studies that have emphasized statistical testing to indicate meaningful subgroups. Second, we leveraged MCIDs to aid interpretation of the magnitude of stratum-specific effects. For walking capacity, several prior studies have estimated MCID for the self-paced walking test as an increase in 319 to 376 m. [36, 49, 50]

An increase of 400 m may allow older adults significant independence, as walking distances of 200 to 500 m are often considered walkable for older adults, allowing individuals to navigate parks, stores, and other community resources. [64, 65] For SSSQ we used and MCID range from 4.2 to 5.5 points, which is based on prior analyses of our sample. [36] However, it is important to note that SSSQ improvements>4 points might be considered large, as prior studies have estimated MCIDs to be lower (e.g., approximately 12 points when combining symptom and function domains). [66, 67] However, it is also possible that prior studies enrolled participants with more advanced disease and a worse prognosis.[66, 67]

Our study represents an important first step in understanding subgroups of patients with LSS that are more likely to benefit from manual therapy and individualized exercise when compared to other nonsurgical approaches. We anticipate that our findings can inform hypotheses that can be pre-specified and tested in a future large trial. Furthermore, the use of existing frameworks, such as the Instrument for assessing the Credibility of Effect Modification Analyses (ICEMAN), can improve the credibility of effect modification analyses. [68] While our analyses may have met some of the relevant ICEMAN criteria (use of clinically important thresholds to define subgroups; statistical interaction testing), others were not met.

For example, we did not pre-specify the hypothesized direction of effects in each subgroup and could not compare our subgroup treatment effects to prior studies. Consistent with our exploratory approach we evaluated many potentially important subgroups, rather than testing a small set of suspected treatment effect modifiers. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that meeting all ICEMAN criteria is important for establishing credible subgroups that can be widely implemented in usual medical care to tailor care and improve patient outcomes.

Conclusions

Among older adults with lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) receiving nonsurgical treatments, improvements in stenosis-related symptoms and function were larger among younger, non-white, and non-smoking participants, and those with higher symptom and function burden on the SSSQ or the Oswestry Disability Index at baseline. Improvements on walking capacity were also larger among younger participants, participants without knee osteoarthritis and those with higher baseline physical activity levels. However, relatively few baseline characteristics defined subgroups of participants who had larger improvements with manual therapy and individualized exercise when compared to group exercise or usual medical care groups. Larger trials are needed to test our findings and identify additional characteristics that may guide clinical decision making for providing nonsurgical treatment options to patients with LSS.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material 1 Literature review (Supplemental file 1):

CONTENTS:

Appendix Table 1. Search strategies

Appendix Table 2. Overview of studies evaluating predictors and/or effect modifiers of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) symptoms, function and walking capacity

Appendix Table 3. Predictors of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) symptoms, function and walking capacity

Appendix Table 4. Potential treatment effect modifiers of of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) symptoms, function and walking capacity.

Additional tables:Appendix Table 5. Predictors of 2-month change in lumbar spinal stenosis symptom severity and function on the total score of the Swiss Spinal Stenosis (SSS)

Appendix Table 6. Predictors of 2-month change in walking distance on self-paced walking test

Appendix Table 7. Treatment effect modification of Manual Therapy and Exercise compared to Group Exercise (GE) and Medical Care (MC) for change in disability on the Swiss Spinal Stenosis symptom severity scale at 2 months.

Appendix Table 8. Treatment effect modification of Manual Therapy and Exercise compared to Group Exercise (GE) and Medical Care (MC) for change in walking distance on self-paced walking test at 2 months.Funding

This study was funded through Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) award CER-1410-25056. Additional support for work on this manuscript came from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH Grant #s: R01AT012534, K23AT010487 and K24AT011561). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of PCORI or NCCIH.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References:

Jensen RK, Harhangi BS, Huygen F, Koes B.

Lumbar spinal stenosis.

BMJ. 2021;373:n1581.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1581.Katz JN, Zimmerman ZE, Mass H, Makhni MC.

Diagnosis and management of lumbar spinal stenosis:

a review.

JAMA. 2022;327(17):168899.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.5921.Ravindra VM, Senglaub SS, Rattani A, et al.

Degenerative lumbar spine disease:

estimating global incidence and worldwide volume.

Glob Spine J. 2018;8(8):78494.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568218770769.Jensen RK, Jensen TS, Koes B, Hartvigsen J.

Prevalence of lumbar spinal stenosis in general and

clinical populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Eur Spine J. 2020;29(9):214363.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-020-06339-1.Norden J, Smuck M, Sinha A, Hu R, Tomkins-Lane C.

Objective measurement of free-living physical activity (performance)

in lumbar spinal stenosis: are physical activity guidelines being met?

Spine J. 2017;17(1):2633.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2016.10.016.Roseen EJ, Rajendran I, Stein P, et al.

Association of back pain with mortality:

a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies.

J Gen Intern Med. 2021.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06732-6.Hijikata Y, Kamitani T, Otani K, Konno S, Fukuhara S, Yamamoto Y.

Association of lumbar spinal stenosis with severe disability

and mortality among community-dwelling older adults:

the locomotive syndrome and health outcomes

in the Aizu cohort study.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021;46(14):E78490.

https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000003912.Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D.

National trends in the surgical treatment for lumbar

degenerative disc disease: United States, 2000 to 2009.

Spine J. 2015;15(2):26571.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2014.09.026.Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI, Kreuter W, Goodman DC, Jarvik JG.

Trends, major medical complications, and charges

associated with surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis

in older adults.

JAMA. 2010;303(13):125965.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.338.Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Wu YA, Deyo RA, Singer DE.

Long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management

of lumbar spinal stenosis: 8 to 10 year results

from the Maine lumbar spine study.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(8):93643.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000158953.57966.c0.Atlas SJ, Delitto A.

Spinal stenosis: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment.

Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:198207.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000198722.70138.96.Fritsch CG, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, et al.

The clinical course of pain and disability following

surgery for spinal stenosis: a systematic review

and meta-analysis of cohort studies.

Eur Spine J. 2017;26(2):32435.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4668-0.Deyo RA, Hickam D, Duckart JP, Piedra M.

Complications after surgery for lumbar stenosis

in a veteran population.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38(19):1695702.

https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31829f65c1.Bussieres A, Cancelliere C, Ammendolia C, et al.

Non-Surgical Interventions for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Leading

to Neurogenic Claudication: A Clinical Practice Guideline

J Pain 2021 (Sep); 22 (9): 10151039Comer C, Ammendolia C, Battie MC, et al.

Consensus on a standardised treatment pathway algorithm

for lumbar spinal stenosis: an international Delphi study.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):550.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05485-5.McIlroy S, Walsh E, Sothinathan C, et al.

Pre-operative prognostic factors for walking capacity after

surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a systematic review.

Age Ageing. 2021;50(5):152945.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab150.Petrucci G, Papalia GF, Ambrosio L, et al.

The influence of psychological factors on postoperative

clinical outcomes in patients undergoing lumbar spine

surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Eur Spine J. 2025;34(4):140919.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-025-08733-z.Weiner DK, Holloway K, Levin E, et al.

Identifying biopsychosocial factors that impact

decompressive laminectomy outcomes in veterans

with lumbar spinal stenosis:

a prospective cohort study.

Pain. 2021;162(3):83545.

https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.

0000000000002072.McIlroy S, Jadhakhan F, Bell D, Rushton A.

Prediction of walking ability following posterior

decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis.

Eur Spine J. 2021;30(11):330718.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-021-06938-6.Morales A, El Chamaa A, Mehta S, Rushton A, Battie MC.

Depression as a prognostic factor for lumbar

spinal stenosis outcomes: a systematic review.

Eur Spine J. 2024;33(3):85171.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-023-08002-x.McKillop AB, Carroll LJ, Battie MC.

Depression as a prognostic factor of lumbar

spinal stenosis: a systematic review.

Spine J. 2014;14(5):83746.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2013.09.052.Rubin DI.

Epidemiology and risk factors for spine pain.

Neurol Clin. 2007;25(2):35371.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncl.2007.01.004.Tomkins-Lane CC, Holz SC, Yamakawa KS, et al.

Predictors of walking performance and walking capacity

in people with lumbar spinal stenosis, low back pain,

and asymptomatic controls.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(4):64753.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2011.09.023.Lesko CR, Henderson NC, Varadhan R.

Considerations when assessing heterogeneity of treatment

effect in patient-centered outcomes research.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;100:2231.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.04.005.Roseen EJ, Gerlovin H, Felson DT, Delitto A, Sherman KJ, Saper RB.

Which chronic low back pain patients respond favorably

to yoga, physical therapy, and a self-care book?

Responder analyses from a randomized controlled trial.

Pain Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnaa153.Beneciuk JM, George SZ, Patterson CG, et al.

Treatment effect modifiers for individuals with acute

low back pain: secondary analysis of the TARGET trial.

Pain. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1097/

j.pain.0000000000002679.Costa Lda C, Koes BW, Pransky G, Borkan J, Maher CG, Smeets RJ.

Primary care research priorities in low back pain:

an update.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38(2):14856.

https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e318267a92f.Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, et al.

Report of the NIH Task Force on Research

Standards for Chronic Low Back Pain

Journal of Pain 2014 (Jun); 15 (6): 569585Gurung T, Ellard DR, Mistry D, Patel S, Underwood M.

Identifying potential moderators for response to

treatment in low back pain: a systematic review.

Physiotherapy. 2015;101(3):24351.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2015.01.006.Schneider M, Ammendolia C, Murphy D, et al.

Comparison of non-surgical treatment methods for

patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: protocol

for a randomized controlled trial.

Chiropr Man Therap. 2014;22:19.

https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-709X-22-19.Schneider MJ, Ammendolia C, Murphy DR, et al.

Comparative Clinical Effectiveness of Nonsurgical Treatment

Methods in Patients With Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

A Randomized Clinical Tria

JAMA Netw Open 2019 (Jan 4); 2 (1): e186828Ammendolia C, Cote P, Southerst D, et al.

Comprehensive nonsurgical treatment versus self-directed

care to improve walking ability in lumbar spinal

stenosis: a randomized trial.

Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(12):240819.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.05.014.Murphy DR, Hurwitz EL, Gregory AA, Clary R.

A Non-surgical Approach to the Management of

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A Prospective

Observational Cohort Study

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006 (Feb 23); 7: 16Comer CM, Conaghan PG, Tennant A.

Internal construct validity of the Swiss Spinal Stenosis

questionnaire: Rasch analysis of a disease-specific

outcome measure for lumbar spinal stenosis.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(23):196976.

https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181fc9daf.Abou-Al-Shaar H, Adogwa O, Mehta AI.

Lumbar spinal stenosis: objective measurement

scales and ambulatory status.

Asian Spine J. 2018;12(4):76574.

https://doi.org/10.31616/asj.2018.12.4.765.Carlesso C, Piva SR, Smith C, Ammendolia C, Schneider MJ.

Responsiveness of outcome measures in nonsurgical

patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a secondary

analysis from a randomized controlled trial.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021;46(12):78895.

https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000003920.Ammendolia C, Schneider M, Williams K, et al.

The Physical and Psychological Impact of Neurogenic

Claudication: The Patients' Perspectives

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2017 (Mar); 61 (1): 1831Tomkins CC, Battie MC, Rogers T, Jiang H, Petersen S.

A criterion measure of walking capacity in lumbar spinal

stenosis and its comparison with a treadmill protocol.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(22):24449.

https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b03fc8.Tomkins-Lane CC, Battie MC.

Validity and reproducibility of self-report measures

of walking capacity in lumbar spinal stenosis.

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(23):2097102.

https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f5e13b.Roseen EJ, Ward RE, Keysor JJ, Atlas SJ, Leveille SG, Bean JF.

The association of pain phenotype with neuromuscular

impairments and mobility limitations among older

primary care patients: a secondary analysis of the

Boston rehabilitative impairment study of the elderly.

PM&R. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12336.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB.

The Oswestry Disability Index

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000 (Nov 15); 25 (22): 29402952Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, et al.

Development of criteria for the classification and reporting

of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of

the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria

Committee of the American Rheumatism Association.

Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):103949.Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, et al.

The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the

classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip.

Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34(5):50514.Choi SW, Reise SP, Pilkonis PA, Hays RD, Cella D.

Efficiency of static and computer adaptive short forms

compared to full-length measures of depressive symptoms.

Qual Life Res. 2010;19(1):12536.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9560-5.Woby SR, Roach NK, Urmston M, Watson PJ.

Psychometric properties of the TSK-11:

a shortened version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia.

Pain. 2005;117(12):13744.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.029.Smeets RJ, Beelen S, Goossens ME, Schouten EG, Knottnerus JA, Vlaeyen JW.

Treatment expectancy and credibility are associated with

the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral

treatment in chronic low back pain.

Clin J Pain. 2008;24(4):30515.

https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e318164aa75.Fox MP, Murray EJ, Lesko CR, Sealy-Jefferson S.

On the need to revitalize descriptive epidemiology.

Am J Epidemiol. 2022;191(7):11749.

https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwac056.Trigg A, Griffiths P.

Triangulation of multiple meaningful change thresholds

for patient-reported outcome scores.

Qual Life Res. 2021;30(10):275564.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-02957-4.Rainville J, Childs LA, Pena EB, et al.

Quantification of walking ability in subjects with

neurogenic claudication from lumbar spinal stenosis

a comparative study.

Spine J. 2012;12(2):101.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2011.12.006.Tomkins-Lane CC, Battie MC, Macedo LG.

Longitudinal construct validity and responsiveness of measures

of walking capacity in individuals with lumbar spinal stenosis.

Spine J. 2014;14(9):193643.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2013.11.030.Turner JA, Comstock BA, Standaert CJ, et al.

Can patient characteristics predict benefit from epidural

corticosteroid injections for lumbar spinal stenosis symptoms?

Spine J. 2015;15(11):231931.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2015.06.050.Takenaka H, Sugiura H, Kamiya M, et al.

Predictors of walking ability after surgery for

lumbar spinal canal stenosis: a prospective study.

Spine J. 2019;19(11):182431.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2019.07.002.Sinikallio S, Aalto T, Airaksinen O, et al.

Depression is associated with poorer outcome of

lumbar spinal stenosis surgery.

Eur Spine J. 2007;16(7):90512.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-007-0349-3.Fokter SK, Yerby SA.

Patient-based outcomes for the operative treatment

of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis.

Eur Spine J. 2006;15(11):16619.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-005-0033-4.Sinikallio S, Aalto T, Lehto SM, et al.

Depressive symptoms predict postoperative disability among

patients with lumbar spinal stenosis: a two-year

prospective study comparing two age groups.

Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(6):4628.

https://doi.org/10.3109/09638280903171477.Thornes E, Ikonomou N, Grotle M.

Prognosis of surgical treatment for degenerative lumbar

spinal stenosis: a prospective cohort study of clinical

outcomes and health-related quality of life

across gender and age groups.

Open Orthop J. 2011;5:3728.

https://doi.org/10.2174/1874325001105010372.Roseen EJ, Smith CN, Essien UR, et al.

Racial and ethnic disparities in the incidence of

high-impact chronic pain among primary care

patients with acute low back pain:

a cohort study.

Pain Med. 2023;24(6):63343.

https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnac193.Shi T, Chen Z, Hu D, Li W, Wang Z, Liu W.

Does type 2 diabetes affect the efficacy of therapeutic

exercises for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis?

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):198.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06305-0.Schneider MJ, Terhorst L, Murphy D, Stevans JM, Hoffman R, Cambron JA.

Exploratory analysis of clinical predictors of outcomes

of nonsurgical treatment in patients with

lumbar spinal stenosis.

J Manipul Physiol Ther. 2016;39(2):8894.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2016.01.001.Rainville J, Bono JV, Laxer EB, et al.

Comparison of the history and physical examination

for hip osteoarthritis and lumbar spinal stenosis.

Spine J. 2019;19(6):100918.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2019.01.006.Young JJ, Kongsted A, Jensen RK, et al.

Characteristics associated with comorbid lumbar spinal

stenosis symptoms in people with knee or hip osteoarthritis:

an analysis of 9,136 good life with osteoArthritis

in Denmark (GLA:D(R)) participants.

BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):250.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06356-3.Hicks GE, George SZ, Pugliese JM, et al.

Hip-focused physical therapy versus spine-focused physical

therapy for older adults with chronic low back pain at

risk for mobility decline (MASH): a multicentre,

single-masked, randomised controlled trial.

Lancet Rheumatol. 2024;6(1):e1020.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00267-9.Liu P, Wu Y, Xiao Z, et al.

Estimating individualized treatment effects using a

risk-modeling approach: an application to epidural

steroid injections for lumbar spinal stenosis.

Pain. 2023;164(4):8119.

https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002768.Hirsch JA, Winters M, Ashe MC, Clarke P, McKay H.

Destinations that older adults experience within their

GPS activity spaces relation to objectively

measured physical activity.

Environ Behav. 2016;48(1):5577.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916515607312.Besser LM, Chang LC, Evenson KR, et al.

Associations between neighborhood park access and

longitudinal change in cognition in older adults:

the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.

J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;82(1):22133.

https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-210370.Cleland JA, Whitman JM, Houser JL, Wainner RS, Childs JD.

Psychometric properties of selected tests in patients

with lumbar spinal stenosis.

Spine J. 2012;12(10):92131.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2012.05.004.Mannion AF, Fekete TF, Wertli MM, et al.

Could less be more when assessing patient-rated

outcome in spinal stenosis?

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(10):7108.Schandelmaier S, Briel M, Varadhan R, et al.

Development of the instrument to assess the credibility

of effect modification analyses (ICEMAN) in

randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses.

CMAJ. 2020;192(32):E9016.

https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200077.

Return to SPINAL STENOSIS

Return to SPINAL PAIN MANAGEMENT

Since 12-10-2025

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |