Initial Choice of Spinal Manipulative Therapy

for Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain Leads

to Reduced Long-term Risk of Adverse Drug

Events Among Older Medicare BeneficiariesThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2021 (Dec 15); 46 (24): 1714–1720 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS James M Whedon • Anupama Kizhakkeveettil • Andrew Wj Toler • Todd A MacKenzie, et al.

Southern California University of Health Sciences,

Whittier, CA.

Study design: Retrospective observational study.

Objective: Opioid Analgesic Therapy (OAT) and Spinal Manipulative Therapy (SMT) are evidence-based strategies for treatment of chronic low back pain (cLBP), but the long-term safety of these therapies is uncertain. The objective of this study was to compare OAT versus SMT with regard to risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) among older adults with cLBP.

Summary of background data: We examined Medicare claims data spanning a 5-year period on fee-for-service beneficiaries aged 65 to 84 years, continuously enrolled under Medicare Parts A, B, and D for a 60-month study period, and with an episode of cLBP in 2013. We excluded patients with a diagnosis of cancer or use of hospice care.

Methods: All included patients received long-term management of cLBP with SMT or OAT. We assembled cohorts of patients who received SMT or OAT only, and cohorts of patients who crossed over from OAT to SMT or from SMT to OAT. We used Poisson regression to estimate the adjusted incidence rate ratio for outpatient ADE among patients who initially chose OAT as compared with SMT.

Results: With controlling for patient characteristics, health status, and propensity score, the adjusted rate of ADE was more than 42 times higher for initial choice of OAT versus initial choice of SMT (rate ratio 42.85, 95% CI 34.16-53.76, P < 0.0001).

Conclusion: Among older Medicare beneficiaries who received long-term care for cLBP the adjusted rate of adverse drug events (ADEs) for patients who initially chose OAT was substantially higher than those who initially chose SMT. Level of Evidence: 2.

Keywords: Spinal Manipulation, Opioids, Low Back Pain, Adverse Drug Events, Medicare, Non-pharmacological

Mini Abstract: Among older Medicare beneficiaries who initiated long-term care of chronic low back pain with opioid analgesic therapy, the adjusted rate of outpatient adverse drug events was more than 42 times higher as compared to those who initially chose spinal manipulative therapy (rate ratio 42.85, 95% CI 34.16–53.76, p <.0001).

From the FULL TEXT Article:

INTRODUCTION

Recent reviews have noted that there is insufficient evidence to justify the use of many treatments for low back pain (LBP). [1, 2] Current evidence-based guidelines for clinical management of chronic low back pain (cLBP) include both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. [3] Both Opioid Analgesic Therapy (OAT) [4, 5] and Spinal Manipulative Therapy (SMT) [6, 7] are considered effective treatments for cLBP and are provided under Medicare for older adults with cLBP.

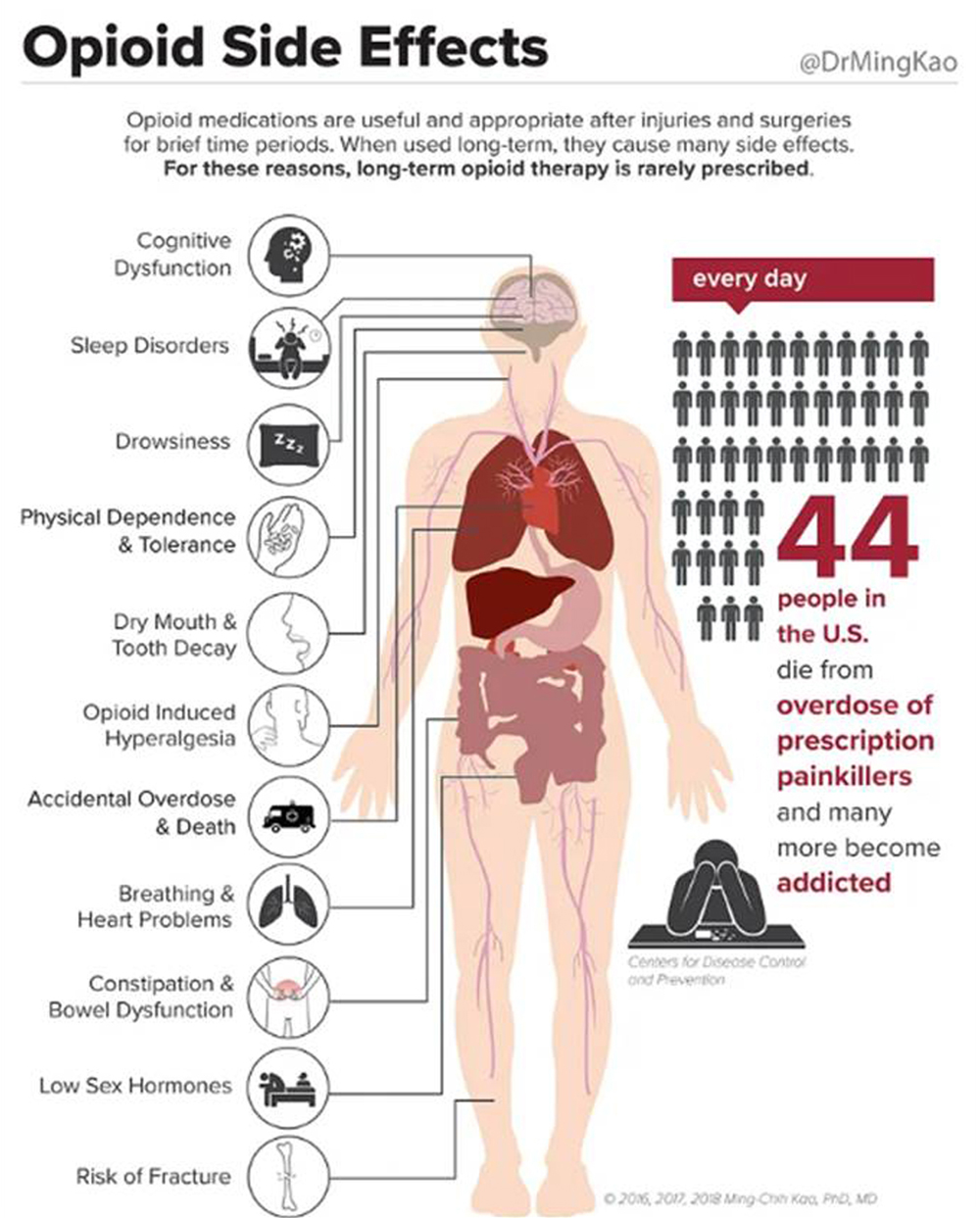

However, the long-term safety of OAT for patients with cLBP is uncertain. [8] The dangers of opioid misuse have been exhaustively documented, and overprescribing has been considered a leading cause of the ongoing opioid crisis in the US. [9, 10] The safety of long-term opioid therapy for treatment of chronic pain is of particular concern. From 1999 to 2010, physician office visits for complaints of neck or back pain that resulted in an opioid prescription increased from 19% to 29%. [11]

The elderly are at particularly high risk of adverse drug events (ADEs), [12] but older adults nevertheless receive more opioid analgesics than any other age group. [13] Opioid use in the Medicare Advantage population actually increased from 2011 to 2016, [14] and from 2017 to 2018, among persons over age 65, deaths due to opioid overdose increased. [10]

SMT is established as an effective non-pharmacologic treatment for cLBP, but little is known about the safety of long-term treatment with SMT. [4] Most SMT in the US is provided by chiropractors. [15] Recent observational studies have found that utilization of chiropractic care for patients with LBP is associated with decreased opioid use, [16–18] and reduced risk of ADEs. [19] However, for long-term ongoing supportive care of cLBP, the risk of continuing either OAT or SMT is uncertain, particularly for the high-risk older adult population covered under Medicare Part B. The objective of this study was to compare SMT and OAT to determine the impact of SMT on the risk of ADEs among older adults receiving long-term care for cLBP.

METHODS

Design

We tested the hypothesis that among older Medicare beneficiaries with cLBP, recipients of OAT have higher rates of ADEs as compared to recipients of SMT. Our approach to testing this hypothesis was to analyze nationally representative Medicare claims data differences in outcomes between four cohorts – those treated with long-term OAT, those treated with long-term SMT, those initially treated with OAT followed by long-term SMT, and those initially treated with SMT followed by long-term OAT. We conducted a retrospective study using fee-for-service (FFS) claims data spanning the five-year period from 2012 through 2016. We combined elements of cohort and crossover-cohort design to evaluate for comparative rates of ADEs. This study was conducted in accordance with a data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which allowed access to Medicare administrative data for research purposes. In accordance with CMS rules for analysis of health claims, cells with n<11 were suppressed to prevent disclosure of protected health information. The research methods were reviewed and approved by the principal investigator’s institutional review board. This study was conducted in the context of a multi-aim NIH-funded investigation of the comparative value of OAT vs. SMT for long-term care of Medicare beneficiaries with cLBP. Thus, aspects of the methods used for sampling and cohort assembly are identical to those described in reports on other aims of the research project.

Population and Sampling

The study population included non-institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries aged 65–84 years, alive as of Jan/01/12, residing in a US state or the District of Columbia, and continuously enrolled under Medicare Parts A, B and D for the 60-month study period beginning Jan/01/12 and ending Dec/31/16. We defined an episode of cLBP as occurring with the recording of two claims with diagnosis of LBP at least 90 days apart. [20] LBP was identified by ICD-9 diagnosis code. Claims were restricted to outpatient office visits as defined by Place of Service code 11. Claims were further restricted by Provider Specialty Code to those for the specialties of General Practice, Family Practice, Internal Medicine, Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Chiropractic, Physical Therapist in Private Practice, or Pain Management. We excluded patients with a diagnosis of cancer or use of hospice care.

Cohort Definitions

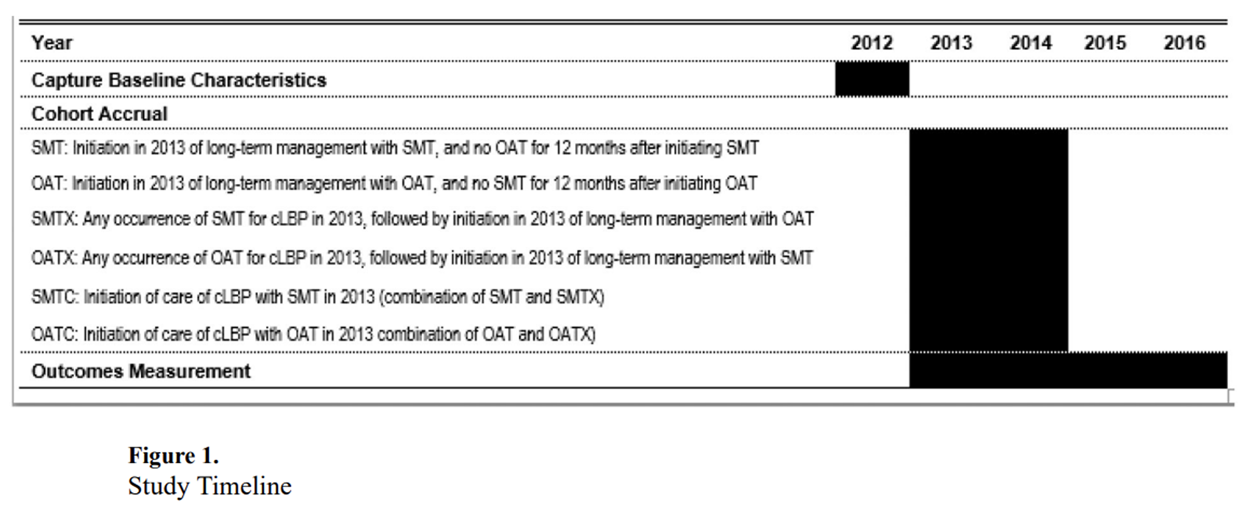

Figure 1 We assembled cohorts of patients who received long term management of cLBP with SMT or OAT. [Figure 1] SMT was identified in clinical claims data by current procedural terminology (CPT) codes 98940, 98941 and 98942. OAT was identified as prescription opioid analgesics or prescription analgesics containing opioids, identified by drug code and obtained through an outpatient pharmacy. For OAT, we defined long-term management as 6 or more standard 30-day supply prescription fills in a 12-month period. [21, 22] For SMT, we defined long-term management as >12 office visits for spinal manipulation for LBP in any 12-month period, including at least one visit per month. [20, 23–25]

The point of accrual to a cohort (index date) for patients in each group was the date of the first office visit associated with an episode of cLBP. For patients with more than one episode of cLBP, only the first episode was counted for purposes of cohort accrual. A look-back period, defined as the 12-month period ending with the index date, allowed exercise of population inclusion and exclusion criteria, and measurement of comorbidity scores. We assembled two primary cohorts of patients, and two crossover cohorts. For purposes of analysis, we also created combined cohorts, based upon the patient’s first choice of treatment (SMT or OAT). [Figure 1]

Patient Characteristics

We collected data on the demographic characteristics of included patients. Patient age in years at time of cohort accrual was categorized as 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, and 80–84. Sex as a biological variable was collected as male or female. Race and ethnicity data are multiply categorized in CMS data, but adherence to data suppression rules required aggregating these data to only two categories: “White” and “Other / Unknown”. We measured socioeconomic status in two ways: designation of Medicare beneficiary eligibility for the Part D low-income subsidy, and dual eligibility for both Medicare and Medicaid; Both measures may be considered indicators of lower socioeconomic status. We also collected data on the health status of included patients, including Charlson comorbidity scores, which were calculated for each patient based upon diagnoses recorded during the 12-month period preceding cohort accrual.

The same pre-index period was used to identify diagnosis of comorbid chronic conditions (osteoarthritis of the hip or knee, which may confound the indication for opioids, and fibromyalgia and depressive disorder, which may affect prognosis for older adults with cLBP. Diagnostic codes for LBP were categorized as non-specific LBP, radiculopathy, herniated disc, spondylolisthesis, sprain/strain, or spinal stenosis. For patients who received OAT, we also collected data on class of opioid prescribed at time of cohort accrual.

Outcomes Measurement and Statistical Analysis

From index date through 2016, we measured rates of ADEs occurring in an outpatient setting, as indicated by diagnosis code. We generated descriptive statistics on patient characteristics and on the frequency of outcomes for primary cohorts SMT and OAT, crossover cohorts SMTX and OATX, and combined cohorts SMTC and OATC. Because previous studies have found that initial choice of treatment for LBP can significantly affect outcomes, [26, 27] we designed an analysis to estimate the causal difference between initial choice of the two approaches to treatment. We accounted for selection bias by (1) modelling of the outcome by covariates, and (2) propensity scoring by binning. To estimate the adjusted incidence rate ratio using a multivariable model (e.g., ratio of average count) we conducted a comparison of outcomes between cohorts OATC and SMTC using Poisson regression with robust (sandwich) standard errors, controlling for age, sex, race, beneficiary residence ZIP code, Part D low-income subsidy, dual eligibility status, diagnostic category, chronic condition, and Charlson comorbidity score.

We repeated this comparison using a propensity score approach. In the first step we derived a model for the propensity of OATC vs SMTC using a flexible logistic regression (e.g., non-parametric regression including interactions) in terms of the covariates above. In the second and final step of the propensity score approach we compared outcomes between OATC and SMTC using binned propensities (e.g., controlling for the categorical variable created by taking deciles of the propensity). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Table 1

page 12Table 1 displays demographic characteristics and measures of health status by cohort. The overall study sample included 28,160 patients. There were 4,998 patients (18%) in Cohort SMT, 20,947 (74%) in Cohort OAT, 1,431 (5%) in crossover cohort SMTX, and 784 (3%) in crossover cohort OATX. Among the combined cohorts, there were 6,429 patients in cohort SMTC and 21,731 patients in cohort OATC. Within all cohorts, average age at accrual ranged between 72.6 and 73.1; approximately two thirds of patients were 74 years of age or younger. Females outnumbered males by approximately 3:1 within all cohorts. Patients who identified as White greatly outnumbered other racial/ethnic groups within all cohorts. As measured by both Part D low-income subsidy and dual eligibility, the proportion of patients with lower socioeconomic status was approximately five times higher among patients who received only OAT, as compared to those who received only SMT. The proportion of those with indications of lower socioeconomic status were also greater among patients who crossed over from SMT to OAT. Comorbidity scores trended higher among patients who received only OAT, as compared to those who received only SMT, with more than twice the proportion of patients with scores of 2, 3, or 4 in the OAT cohort as compared to the SMT cohort.

In all cohorts most cases of LBP were categorized as non-specific LBP. There were higher proportions of patients diagnosed with radiculopathy and spinal stenosis among patients who received only OAT, as compared to those who received only SMT. Cases of herniated disc and spondylolisthesis also predominated in the OAT cohort, while in the other three cohorts, the frequency of cases was so low that data suppression was required. Diagnosis of sprain/strain occurred infrequently, and frequency data in this category were suppressed for the crossover cohorts.

Regarding the prevalence of chronic comorbidities, higher proportions of patients in the OAT cohort were diagnosed with depression and osteoarthritis of the hip or knee, as compared to the SMT cohort. The combined cohort OATC was more racially diverse than SMTC. Choice of OAT as initial treatment was associated with indications of lower socioeconomic status, higher comorbidity scores, and higher rates of depression and osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. As in the primary and crossover cohorts, most patients in the combined cohorts had non-specific LBP. Diagnoses of radiculopathy, spondylolisthesis and spinal stenosis were higher among patients who chose OAT as the initial approach to treatment.

Regarding class of opioid prescribed at the time of cohort accrual, Class 2 opioids predominated across all three cohorts of opioid users. Use of Class 4 opioids was prescribed for higher proportions of patients in the crossover cohorts than in the OAT cohort. Most patients (81.4%) who initially chose OAT were prescribed a Class 2 opioid; 2.8% received a Class 3 drug, and 15.5% were prescribed Class 4.

Table 2 Table 2 displays by cohort the proportion of patients who experienced an adverse drug event (ADE) . Among patients who received OAT for long-term care of cLBP, 18.3% experienced an ADE in an outpatient setting, as compared to less than 1% among those who received spinal manipulation. Among patients who crossed over from SMT to OAT, the proportion of patients who had an ADE was more than twice as high as the proportion of those who crossed over from OAT to SMT.

In the combined cohorts the frequency of ADE in the OATC cohort was higher in every category of ADE as compared to the SMTC. Opioid dependence or abuse was most prevalent among patients who received OAT for long-term care at 14.3%, while only 0.3% of patients who received SMT were so diagnosed. The low frequency of occurrence of specific types of ADE required suppression of data in numerous categories.

Among older Medicare beneficiaries who initiated care for cLBP via OAT, 17.8% experienced an outpatient ADE, as compared to 3% for those who initially chose SMT. With controlling for patient characteristics, health status and propensity score, the adjusted rate of ADE was more than 42 times higher for initial choice of OAT vs. initial choice of SMT (Rate Ratio 42.85, 95% confidence interval (CI) 34.16–53.76, p <.0001).

DISCUSSION

Patients who received long-term care with SMT and those who initially chose SMT as their approach to treatment received care that was measurably safer than those who chose OAT, at least regarding medication safety. This result is consistent with a previous report, which found that among adults with LBP, the adjusted likelihood of an ADE occurring in an outpatient setting within 12 months was 51% lower among recipients of chiropractic services as compared to nonrecipients. [19]

The number of patients with cLBP who received long-term care with OAT was more than five times higher than the number who received long term care with SMT (20,947 vs. 4,998 respectively), and the rate of occurrence of any ADE in the OAT cohort was more than eighteen times larger in the OAT cohort (3,832 patients; 18.3%) as compared to the SMT cohort (45 patients; 0.9%).

Calculation of number needed to treat shows that on average, 5.7 patients would have to receive SMT instead of OAT to avoid one ADE. Thus, even a small shift in the proportion of patients using SMT could be expected to reduce the risk of ADEs among Medicare beneficiaries with cLBP. The crossover analyses demonstrated that use of SMT and OAT are not mutually exclusive among older adults with cLBP. Among those who initially chose treatment by SMT, 22% crossed over to OAT, and among those who initially chose OAT, 4% crossed over to SMT.

The rate of ADEs in the cohort that was initially treated with OAT and then switched to SMT was nearly 5%. Perhaps most interesting is the difference in rate of ADE between the two cohorts that received long-term OAT: the rate of ADE in the OAT cohort was 18.3%, as compared to the SMTX cohort at 10.6%.

Chiropractors should know that their patients may be taking opioids, should be alert to the occurrence of adverse events, and should collaborate with prescribing clinicians to reduce the impact of ADEs.

Limitations

The general limitations of using health claims data for research include inconsistencies in billing practices and coding. Claims data also lack clinical findings that would allow measurement of and controlling for specific clinical outcomes such as pain severity. Other limitations of this study include a lack of data on certain potential confounders such as indicators of pain severity other than diagnostic category, and diagnoses associated with pharmacy fills. We did not evaluate specifically by the specific number of prescription fills per patient, and claims data contain no information on medication compliance; both factors could confound analysis of rates of ADEs. ADE severity is also not reported in claims data, nor is it feasible to tie medication discontinuation to the incident.

With this study there is potential for confounding by indication. However, we controlled for comorbid chronic conditions such as knee or hip osteoarthritis that might confound the results. We were limited by the available data in our ability to measure differences in the characteristics of patients who choose different care pathways. We employed propensity scoring methodology to minimize risk of selection bias that may result from differences between cohorts, such as a possible predisposition among recipients of SMT to avoid the use of medications. Despite these measures, we were unable to consider all confounding variables, the inherent limitations of observational design inhibit causal inference, and explicit assessment of changes in underlying health status were not possible. However, the analysis of large multi-year claims datasets allows detection of adverse events that are uncommon or may take extended time in treatment to develop.

CONCLUSION

Among older Medicare beneficiaries who received long-term care for chronic low back pain (cLBP) via Opioid Analgesic Therapy (OAT), the adjusted rate of experiencing an adverse drug event (ADE) in an outpatient setting was substantially higher than those who received long-term management for cLBP through spinal manipulative therapy.

Key Points:

Opioid Analgesic Therapy (OAT) and Spinal Manipulative Therapy (SMT) are evidence-based strategies for treatment of chronic low back pain (cLBP), but the long-term safety of both therapies is uncertain.

Among older adults who initiated long-term care of cLBP with OAT, the rate of adverse drug events was substantially higher than those who initially chose SMT.

The number of patients who received long-term care with OAT was more than five times higher than the number for SMT.

Calculation of number needed to treat shows that on average, 5.7 patients would have to receive SMT instead of OAT to avoid one ADE.

Thus, even a small shift in the proportion of patients using SMT could be expected to reduce the risk of ADEs among Medicare beneficiaries with cLBP.

Acknowledgements:

This study was conducted in accordance with data use agreement # DUA: RSCH-2019-52662 with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The authors gratefully acknowledge the valuable contributions of Dr. Ian Coulter, PhD as advisor to this research project, and of student researcher Kayla Sagester.

The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) of the National Institutes of Health (award number 1R15AT010035) funds were received in support of this work.

Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: grants, royalties, payment for lecture, travel/accommodations/meeting expenses.

References:

Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain:

A Systematic Review for an American College

of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 493–505Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al.

Prevention and Treatment of Low Back Pain:

Evidence, Challenges, and Promising Directions

Lancet. 2018 (Jun 9); 391 (10137): 2368–2383Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM.

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and

ChronicLow Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline

From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Jones MR, Ehrhardt KP, et al.

Pain in the Elderly.

Current pain and headache reports 2016;20:23Azad TD, Zhang Y , Stienen MN.

Patterns of Opioid and Benzodiazepine Use in Opioid-Naïve

Patients with Newly Diagnosed Low Back

and Lower Extremity Pain.

JGIM 2020. January;35(1):291–297.Rubinstein SM, de Zoete A, van Middelkoop M, et al.

Benefits and Harms of Spinal Manipulative Therapy for the

Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain: Systematic Review

and Meta-analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials

British Medical Journal 2019 (Mar 13); 364: 1689Whedon JM, Goertz CM, Lurie JD, Stason WB.

Beyond Spinal Manipulation: Should Medicare Expand

Coverage for Chiropractic Services? A Review and

Commentary on the Challenges for Policy Makers

J Chiropractic Humanities 2013 (Aug 28); 20 (1): 9–18Deyo RA, Von Korff M, Duhrkoop D.

Opioids for low back pain.

BMJ 2015; 350:g6380

10.1136/bmj.g6380.Hagemeier NE.

Introduction to the opioid epidemic: the economic burden

on the healthcare system and impact on quality of life.

Am J Manag Care 2018;24:S200–S6.Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith Ht, Davis NL.

Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths -

United States, 2017–2018.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:290–7Mafi JN, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Landon BE.

Worsening Trends in the Management

and Treatment of Back Pain

JAMA Internal Medicine 2013 (Sep 23); 173 (17): 1573–1581Lavan AH, Gallagher P.

Predicting risk of adverse drug reactions in older adults.

Ther Adv Drug Saf 2016;7:11–22.CDC.

2018 Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and

Outcomes — United States. Surveillance Special Report.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services.

Published August 31, 2018. Accessed [10/02/20] at

dc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2018-cdc-drug-

surveillance-report.pdf23.Jeffery MM, Hooten WM, Henk HJ, et al.

Trends in opioid use in commercially insured and

Medicare Advantage populations in 2007–16:

retrospective cohort study.

BMJ 2018;362:k2833.:

10.1136/bmj.k2833Shekelle PG, Adams AH, Chassin MR, Hurwitz EL, Brook RH.

Spinal manipulation for low-back pain.

Ann Intern Med 1992; 117(7): 590–598.Corcoran KL, Bastian LA, Gunderson CG, Steffens C, Brackett A.

Association Between Chiropractic Use and Opioid Receipt

Among Patients with Spinal Pain: A Systematic

Review and Meta-analysis

Pain Medicine 2020 (Feb 1); 21 (2): e139–e145Kazis LE, Ameli O, Rothendler J, et al.

Observational Retrospective Study of the Association of

Initial Healthcare Provider for New-onset Low Back Pain

with Early and Long-term Opioid Use

BMJ Open. 2019 (Sep 20); 9 (9): e028633Whedon JM, Toler AWJ, Kazal LA, Bezdjian S, Goehl JM.

Impact of Chiropractic Care on Use of Prescription

Opioids in Patients with Spinal Pain

Pain Medicine 2020 (Dec 25); 21 (12): 3567–3573Whedon JM, Toler AWJ, Goehl JM, Kazal LA.

Association Between Utilization of Chiropractic Services

for Treatment of Low Back Pain and Risk

of Adverse Drug Events.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2018;41:383–8.Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, et al.

Report of the NIH Task Force on Research

Standards for Chronic Low Back Pain

Spine (Phila Pa) 2014; 39: 1128–1143Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al.

The Effectiveness and Risks of Long-Term

Opioid Treatment of Chronic Pain

Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Number 218

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

AHRQ Publication No. 14-E005-EF (September 2014)Morden NE, Munson JC, Colla CH, et al.

Prescription opioid use among disabled Medicare beneficiaries:

intensity, trends, and regional variation.

Med Care 2014;52:852–9.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al.

Noninvasive Treatments for Low Back Pain

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 169

AHRQ Publication No. 16-EHC004-EF (February 2016)Office of Inspector General,

Hundreds of Millions in Medicare Payments for Chiropractic

Services Did Not Comply with Medicare Requirements 2016

US Department of Health and Human Services

A-09-14-02033 (October 2016)Weigel PA, Hockenberry JM, Wolinsky FD.

Chiropractic Use in the Medicare Population: Prevalence,

Patterns, and Associations With 1-Year Changes

in Health and Satisfaction With Care

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014 (Oct); 37 (8): 542-551Keeney BJ, Fulton-Kehoe D, Turner JA, Wickizer TM, Chan KC.

Early Predictors of Lumbar Spine Surgery After Occupational

Back Injury: Results From a Prospective Study

of Workers in Washington State

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 (May 15); 38 (11): 953–964Liliedahl RL, Finch MD, Axene DV, Goertz CM.

Cost of Care for Common Back Pain Conditions Initiated

With Chiropractic Doctor vs Medical Doctor/Doctor of

Osteopathy as First Physician: Experience of One

Tennessee-Based General Health Insurer

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010 (Nov); 33 (9): 640–643Corsonello A, Pedone C, Incalzi RA. (2010).

Age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes

and related risk of adverse drug reactions.

Current medicinal chemistry 2010; 17(6), 571–584.Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW, Valim C, Mandl K D.

Adverse drug events in the outpatient setting:

an 11-year national analysis.

Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety 2010; 19(9), 901–910.

10.1002/pds.1984 [DOI]Davis MA, Yakusheva O, Liu H, Tootoo J, Titler MG, Bynum JPW.

Access to Chiropractic Care and the Cost

of Spine Conditions Among Older Adults

American J Managed Care 2019 (Aug); 25 (8): e230–e236ACA. (2020).

Medicare: Patient Access to Chiropractic

Retrieved October 15, 2020, from

https://www.acatoday.org/Advocacy/Legislative-

Regulatory-Policy/Medicare/HR3654-Resources.

Return to MEDICARE

Return to OPIOID EPIDEMIC

Return to INITIAL PROVIDER/FIRST CONTACT

Since 11-30-2025

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |