Chiropractic and Spinal Manipulation: A Review of Research

Trends, Evidence Gaps, and Guideline RecommendationsThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Clin Med 2024 (Sep 24); 13 (19): 5668 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Robert J Trager • Geronimo Bejarano • Romeo-Paolo T Perfecto • Elizabeth R Blackwood • Christine M Goertz

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery,

Duke University School of Medicine,

Durham, NC 27710, USA.

Keyword co-occurrence map (1972–2024)Chiropractors diagnose and manage musculoskeletal disorders, commonly using spinal manipulative therapy (SMT). Over the past half-century, the chiropractic profession has seen increased utilization in the United States following Medicare authorization for payment of chiropractic SMT in 1972. We reviewed chiropractic research trends since that year and recent clinical practice guideline (CPG) recommendations regarding SMT. We searched Scopus for articles associated with chiropractic (spanning 1972-2024), analyzing publication trends and keywords, and searched PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science for CPGs addressing SMT use (spanning 2013-2024). We identified 6286 articles on chiropractic. The rate of publication trended upward. Keywords initially related to historical evolution, scope of practice, medicolegal, and regulatory aspects evolved to include randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews. We identified 33 CPGs, providing a total of 59 SMT-related recommendations. The recommendations primarily targeted low back pain (n = 21) and neck pain (n = 14); of these, 90% favored SMT for low back pain while 100% favored SMT for neck pain. Recent CPG recommendations favored SMT for tension-type and cervicogenic headaches. There has been substantial growth in the number and quality of chiropractic research articles over the past 50 years, resulting in multiple CPG recommendations favoring SMT. These findings reinforce the utility of SMT for spine-related disorders.

Keywords: bibliometrics; chiropractic; clinical practice guidelines; low back pain; review; spinal manipulation.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Chiropractic is a health care profession that focuses on the diagnosis and management of musculoskeletal disorders, with an emphasis on those affecting the spine. [1] In the US, chiropractors are often the first clinicians seen for neck pain and low back pain (LBP) [2, 3], and most often use spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) to address these conditions. [4] The use of chiropractic services has steadily increased in the United States (US), rising from a 12-month prevalence rate of approximately 4% in 1980 to 7% in 2002, and most recently 11% in 2022. [5-7]

Since the 1970s, the chiropractic profession has seen a dramatic transformation both internally and with respect to its place in the health care landscape. Internally, a stronger foundation in chiropractic educational standards and increased rigor of national board examinations were instituted in the 1960s through the 1970s. [1, 8] This was followed by an increase in the quantity and quality of chiropractic research, with studies primarily focused on examining the hallmark intervention of SMT. [1] These efforts were accelerated in 1986 when the US Supreme Court upheld a lower-court decision to protect the chiropractic profession against elimination by the American Medical Association. [9] A byproduct of this forward progress was the development of the first clinical practice guideline (CPG) to recommend SMT for LBP, authored by the US Agency for Health Care Policy and Research in 1994. [10]

The authorization of Medicare coverage for chiropractic SMT in 1972 was a major milestone in chiropractic history. [11, 12] This government-funded health insurer for older adults and younger people with disabilities often sets a precedent for other payers, including Medicaid and commercial insurance. Accordingly, from the 1970s through the 1990s, laws mandating commercial coverage of chiropractic care also increased. [8] New chiropractic schools have been established over the past 10 years [13], with plans to open a chiropractic educational program at the University of Pittsburgh in 2025, the first such program to be embedded within a large public university. [14] In addition, there are more options for postgraduate education programs (i.e., residencies, fellowships, and board certifications) available for doctors of chiropractic. [15] In the US, as of 2019, five percent of chiropractors practice within integrative or hospital-based departments [16] and are in increasing demand in these settings. [17] Moreover, a growing number of chiropractors are actively conducting research in integrative settings in the US. [18]

Given the evolving landscape of the chiropractic profession, we aimed to assess trends in research since the authorization of Medicare coverage in 1972 and the current state of SMT-related clinical practice guideline (CPG) recommendations from 2013 to 2024 to(1) identify gaps between the current state of the science and insurance coverage policies and

(2) inform future research agendas.

Materials and Methods

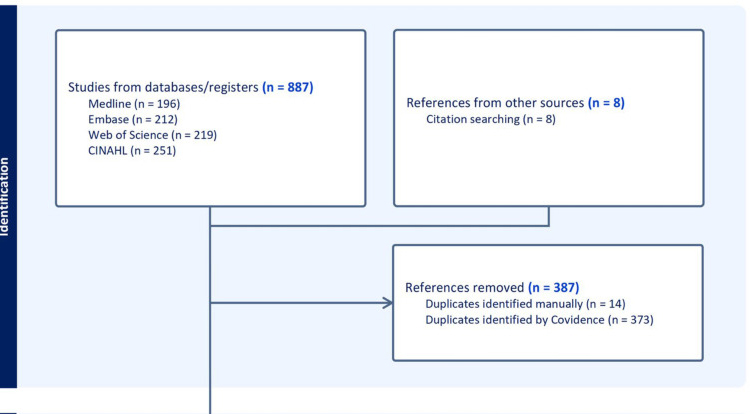

This review used a state-of-the-art approach to synthesize chiropractic research from 1972 through 11 March 2024. [19] This narrative review incorporated elements of bibliometric analysis to identify publication trends and keywords related to chiropractic research and practice [20], evidence mapping to identify trends and gaps in CPGs [21], and a qualitative analysis to highlight major themes and future directions. Search strategies were developed and conducted by a professional medical librarian (EB) in consultation with the author team and included a mix of keywords and subject headings representing SMT and guidelines using a validated guideline filter. [22] Complete reproducible search strategies, including search filters, for all databases are detailed in Supplemental File S1. All citations were imported into Covidence (Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia, 2024), a systematic review screening software, which also de-duplicated the citations. All searches were executed on 14 March 2024. This review article is based exclusively on the analysis of previously published literature. It does not involve any primary research with human participants, animal subjects, or medical record review. Consequently, this work did not require approval from an institutional review board or ethics committee.

To examine publication trends, we searched Scopus for journal articles and reviews with a publication date from 1972 onwards having chiropract* or chiroprax* within the title, abstract, and/or keywords. The search limiters excluded gray literature (i.e., non-traditional publications such as books, book chapters, conference material, editorials, errata, notes, and press releases) and animal research using filters related to animals and/or veterinary publications (Supplemental File S1).

To identify CPGs, searches were conducted in MEDLINE via PubMed, Embase via Elsevier, Web of Science via Clarivate, and CINAHL via EBSCOhost (Supplemental File S1). We required a publication date of at least 2013 to fulfill our objective of examining more current, up-to-date CPGs. We included CPGs described as consensus statements/guidelines, practice guidelines, or similar terminology. [23] Such guidelines were required to be applicable to any population receiving SMT. Guidelines limited to osteopathic manipulation, manipulation under anesthesia, those not written in English, and gray literature were excluded. CPGs were considered that provided recommendations regarding the appropriateness of SMT for a specific condition rather than guidelines regarding the methods of application of SMT. We identified additional CPGs by tracking citations of included articles.

We used Scopus to examine research trends and keywords due to its broad, interdisciplinary coverage and rich keyword indexing, which was used to analyze trends and create visuals. [24] Test searches revealed a greater number of articles with Scopus compared to PubMed or Web of Science. Additionally, this decision was made for logistical reasons. Scopus data can be exported and uploaded to the bibliometric software with minimal manual data cleaning. Furthermore, it is best practice to compare proprietary data from Scopus within the given database rather than across multiple databases. [24, 25] In contrast, our search for CPGs required a more comprehensive approach, using multiple databases with the aim of capturing all relevant guidelines. While the research trend and keyword analyses were broad and descriptive, the CPG search results were used for focused evidence mapping, which necessitated a more rigorous and inclusive strategy to minimize the risk of missing relevant recommendations.

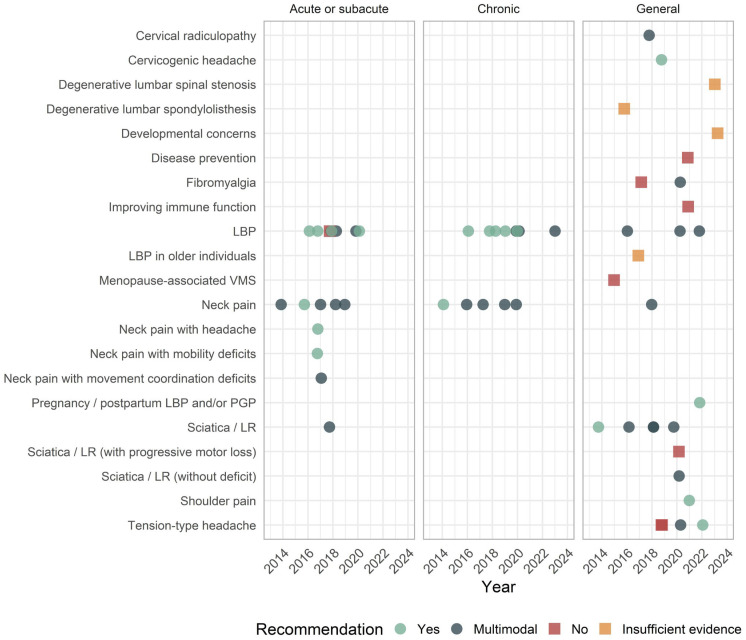

Relevant results were compiled in Covidence [26] and de-duplicated, with the screening of titles/abstracts and full texts performed in duplicate (RT and RP), and data extraction performed by a single author (RT) and verified by a second (GB). Data extracted from CPGs included the author’s surname, year, condition, and recommendation(s). The CPG recommendations were extracted according to a simplified scheme as follows: “Yes” was indicated when SMT was recommended as a viable stand-alone treatment option, regardless of strength of evidence; “Multimodal” when SMT was recommended to be used alongside at least one other therapy such as usual care or exercise; “No” when there was an explicit statement to avoid SMT for the condition altogether; and “Insufficient evidence” when a recommendation could not be derived due to a lack of evidence. The former two recommendations were described as “In favor,” while the latter two were described as “Not in favor”.

We used R (version 4.2.2, Vienna, Austria [27]) along with packages including ggplot2 [28] and tidyr [29] to analyze data extracted from the primary search file exported from Scopus to examine publications per year and cumulative publications. We used the R packages bibliometrix and biblioshiny [30] to import data from our Scopus search and analyze keyword trends over time. Raw search results were imported to bibliometrix, which converted them to a bibliographic data frame and cleaned the text to a consistent format. We used VOSviewer (version 1.6.20) [21] to summarize additional keywords and their interconnections visually. Via R, we used ggplot2 and dplyr [28, 32] to plot a timeline of CPG recommendations.

Results

Publication Trends

Figure 1

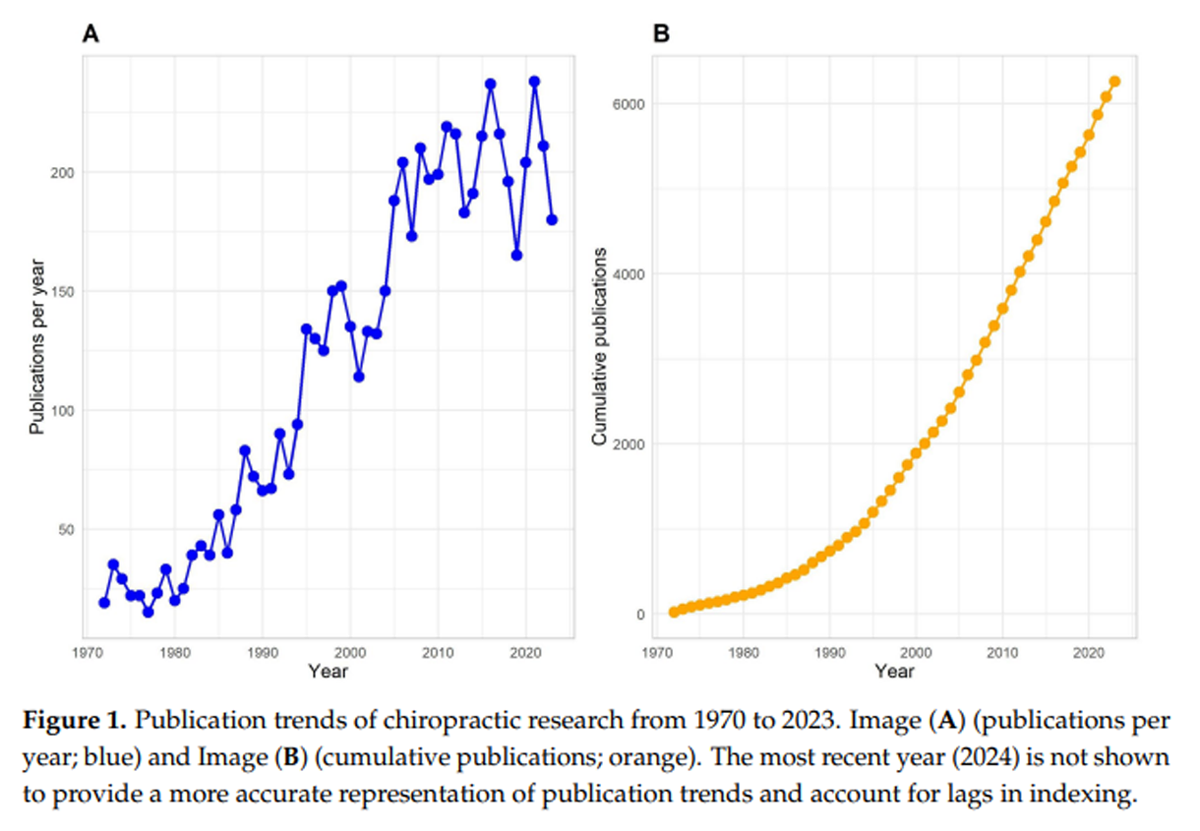

Figure 2 The general Scopus search identified 6,286 chiropractic articles between 1972 and 2024. Few chiropractic research articles were published per year in the early 1970s; however, the rate of publications increased until the 2010s, then remained relatively static until 2023 (Figure 1).

Keywords

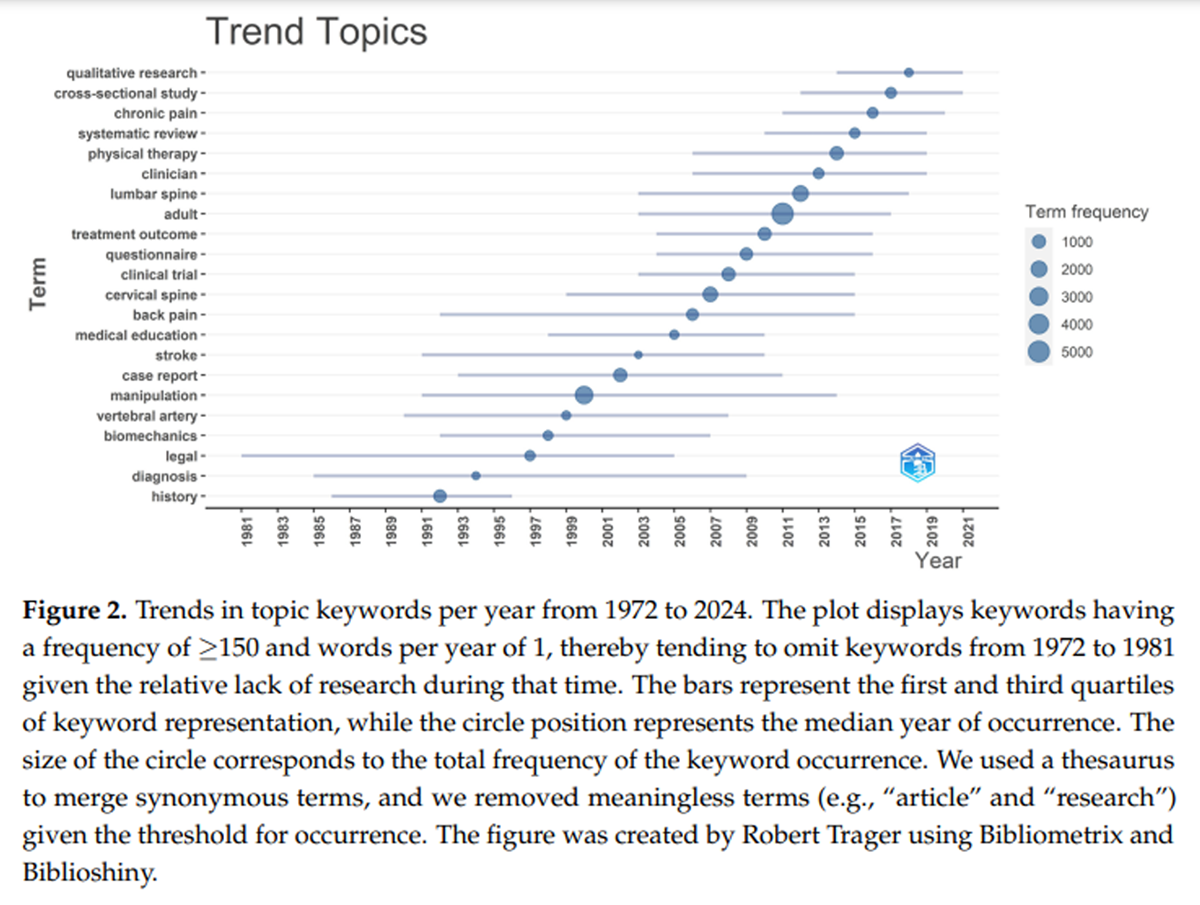

Analysis of the trends in keywords over time revealed distinct patterns in research designs, populations, and topics of focus (Figure 2). Prior to the year 2000, the common keywords included “history”, “diagnosis”, and “legal”. This is accounted for by the corpus of articles focusing on the historical evolution, scope of practice, medicolegal, and regulatory aspects of chiropractic. [33, 34] Around the year 2000, a new theme of keywords emerged, including “vertebral artery”, “manipulation”, “case report”, and “stroke”, likely resulting from numerous case reports published during this time suggesting an association between SMT and adverse vascular events.

Additional keywords emerging from the early 2000s to the mid-2010s highlighted the growth of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining the efficacy of SMT for back pain in adults. Common keywords included “adult”, “clinical trial”, “treatment outcome”, “manipulation”, and “back pain”. A 2019 systematic review on the topic included 47 RCTs, with only one that predated 2000. [35] Keywords from 2015 to 2024 evolved to include “qualitative research”, “cross-sectional study”, “chronic pain”, and “systematic review”. Certain keywords were commonly represented over more than one decade, such as “back pain” (1992–2015), “lumbar spine” (2003–2018), and “cervical spine” (1999–2015).

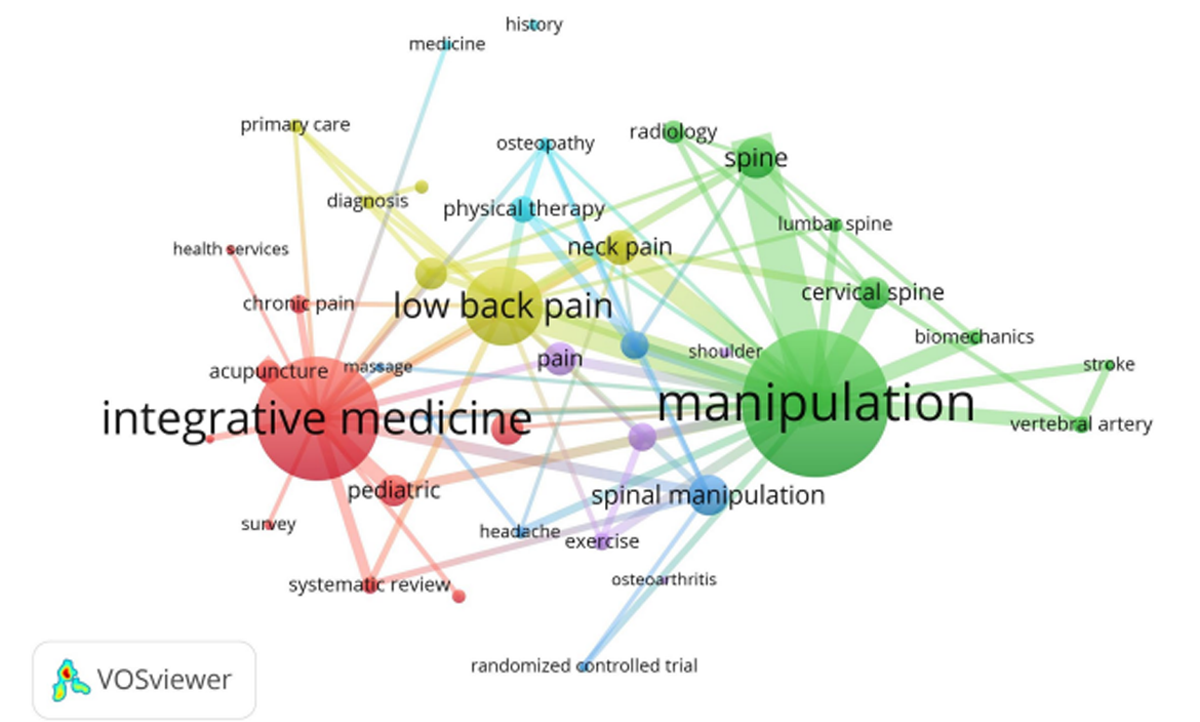

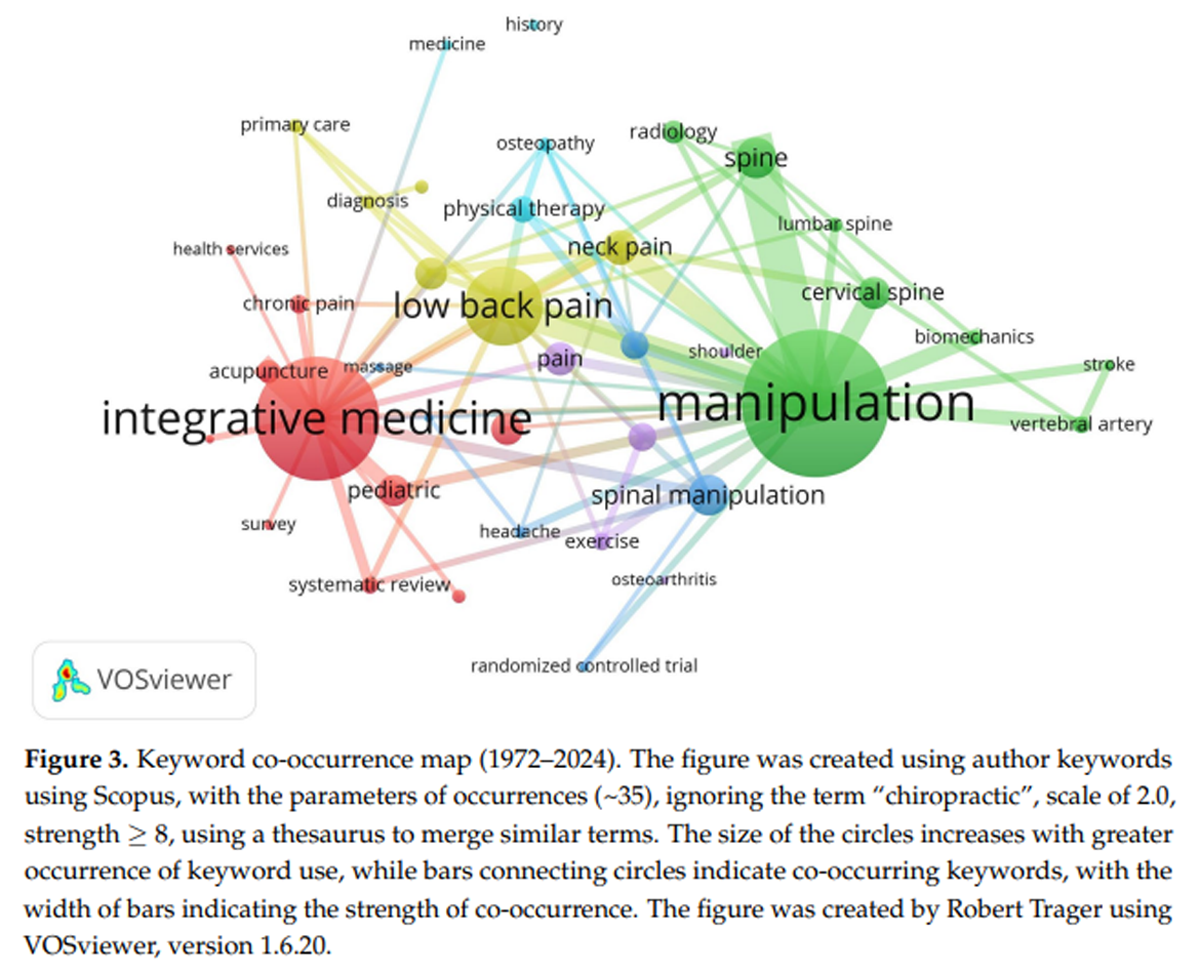

Figure 3 Analysis of keyword co-occurrence demonstrated six clusters centered around the following terms: “manipulation”, “pain”, “integrative medicine”, “manual therapy”, “low back pain”, and “physical therapy” (Figure 3). Regarding the two most occurring terms, “manipulation” tended to co-occur with terms related to the spine (e.g., “lumbar” or “cervical spine”) or vascular conditions (i.e., “vertebral artery” and “stroke”). In contrast, “integrative medicine” often co-occurred with a variety of terms (i.e., “pediatric”, “chronic pain”, and “acupuncture”).

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Figure 4

Table 1

Figure 5 The CPG search identified 500 unique citations (Figure 4). For title/abstract screening, reviewers had 74% agreement (Cohen’s kappa = 0.23 [fair]), and for full-text screening, they had 93% agreement (Cohen’s kappa = 0.85 [almost perfect]). We included 33 CPGs, providing a total of 59 distinct recommendations, as several guidelines provided more than one recommendation [36-68] (Table 1). A list of citations excluded at the full-text phase is available in Supplemental File S2. A single CPG focused exclusively on pediatric patients [52], while another single CPG focused on older adults. [48] When explicitly described, all CPG recommendations focused on individuals with the absence of serious pathology (e.g., cancer, infection, fracture). Several CPGs also outlined red flag indicators of possible serious pathology (e.g., history of malignancy) that would prompt additional evaluation or preclude SMT altogether. [38, 39, 41, 44, 46-52, 54, 57, 59, 66-69]

SMT was most often recommended for LBP (n = 19), neck pain (n = 14), sciatica/lumbar radiculopathy (n = 6), and tension-type headaches (n = 2). The use of SMT for LBP was favored in 90% of statements, while the use of SMT for neck pain was favored in 100% of statements. More recent recommendations favored the use of SMT for pregnancy and postpartum-related LBP (in 2022), cervical radiculopathy (2018), cervicogenic headaches (2019), fibromyalgia (2020), tension-type headaches (2020 and 2022), and shoulder pain (2021), in some cases replacing older recommendations that advised against it for fibromyalgia and tension-type headaches. SMT was specifically not recommended for eight conditions, including degenerative lumbar stenosis and spondylolisthesis, and developmental concerns in children (Figure 5).

Clinical practice guideline recommendations regarding SMT were further categorized based on the duration of symptoms. Accordingly, 100% (8/8) of recommendations for chronic LBP favored SMT, 88% (7/8) for acute/subacute LBP favored SMT, and 80% (4/5) of those for general LBP (regardless of duration) favored SMT. All recommendations for acute/subacute (8/8), chronic (5/5), and general neck pain (1/1) favored SMT (i.e., 100% each; Table 1 and Figure 5).

Discussion

This review found that chiropractic research has focused primarily on the use of SMT for LBP, with a recent emphasis on evidence synthesis and observational studies. While CPG recommendations have evolved, we found that recommendations in favor of SMT for LBP have been established for several years. In addition, there is both a growing interest in the chiropractic management of special populations (e.g., pregnant women, older adults) [48, 65] and growing support for the use of SMT in the management of conditions not confined to the spine (e.g., chronic pain, tension-type and cervicogenic headaches, and shoulder pain). [45, 49, 68]

We identified a progression from case reports to larger and more rigorous study designs, including clinical trials and systematic reviews. For example, consistent with a previous bibliometric study focused on this topic [70], we found a decline over time in the publication of case reports focused on adverse events following chiropractic SMT. Terms such as “legal”, “vertebral artery”, and “stroke” diminished in frequency towards 2010, a trend that has continued as new studies show no definitive causal association between SMT and adverse vascular events such as cervical arterial dissection. [71-73] It is estimated that serious adverse events, such as fractures, are rare and occur between 1 per 2 million manipulations and 13 per 10,000 patients. [74, 75] Likely as a result, SMT is increasingly recommended by CPGs for neck pain [38-40, 42, 43, 49, 53, 66], with some CPGs taking into account the low risk of adverse events when deriving statements favoring SMT. [40, 42, 53]

The recent appearance of “cross-sectional” and “qualitative” study keywords suggests that observational study designs may be increasing in frequency. Recent large observational studies have examined the association between initial provider type and downstream health service utilization among adults with LBP, showing that receiving chiropractic care is associated with a reduced likelihood of costly procedures and greater CPG adherence with respect to medication utilization. [76-80] These designs have several attractive features to examine non-pharmacologic interventions used by chiropractors, including high feasibility, low cost, and applicability to health service utilization and adverse events. [81] Additional studies are needed to further explore markers of care effectiveness and corroborate the already-existing CPG recommendations for chiropractic care among those with LBP. Researchers may also consider using causal inference methods within observational studies, such as instrumental variables and difference-in-differences, to better control for confounding variables and strengthen the studies’ validity. [82]

We found that the number of CPGs recommending the use of SMT has increased across a growing number of musculoskeletal conditions. Most CPG statements that recommended SMT focused on LBP and neck pain either in isolation or as part of a multimodal treatment approach. While most CPGs that considered SMT recommended in favor of its use for spine-related conditions of LBP (90%) and neck pain (100%), three CPG statements found insufficient evidence to recommend SMT for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis and spondylolisthesis. [51, 56, 60] Furthermore, although SMT for sacroiliac joint pain is commonly used by doctors of chiropractic and there is emerging evidence of efficacy [83], we did not identify any current CPGs that addressed the use of SMT for this condition. Such gaps suggest that additional RCTs focusing on individual subsets of LBP and distinct populations may be warranted.

The keyword “headache” was one of the most commonly identified in our search. However, it was only recently that CPGs recommended SMT for both cervicogenic and tension-type headaches (2019–2022). [44, 45, 49] This early interest and subsequent CPG adoption may be explained by the fact that neck pain, commonly treated by chiropractors, is present in approximately 90% of patients with these types of headaches. [84, 85] Of note, “migraine” did not appear in either keyword trends or CPG recommendations despite being one of the most prevalent headache subtypes and often treated by chiropractors. [86] A meta-analysis published in 2020 found that SMT may be effective in reducing pain intensity and days with pain for those with migraine headaches, yet concluded that more research is needed. [87] A larger randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of SMT for migraines is currently underway. [88]

We found only a single CPG dedicated to pediatric patients, although “pediatric” was a common keyword. [52] Most CPG recommendations favoring SMT for LBP generally applied to all adults, including older adults. However, one CPG, published in 2017, found insufficient evidence for treating LBP in adults aged 65 and older, related to a limited number of primary studies dedicated to this population. [48] While age-related physiological changes (e.g., reduced bone mineral density and flexibility) were postulated to play a role in how SMT is used when considering older adults with LBP [48], it remains unclear whether the efficacy of SMT differs in this demographic. In addition, the literature regarding SMT for older adults has continued to grow since the 2017 CPG. Illustratively, a recent clinical trial showed promise with regards to the effectiveness of SMT for lumbar stenosis in older patients. [89] Accordingly, it remains unclear whether future CPG statements would reach a similar conclusion.

This narrative review has several strengths, including the use of a comprehensive search strategy to identify CPGs, the incorporation of multiple data-driven and quantitative strategies to inform our qualitative interpretation of the literature, and the use of manual data extraction for CPG recommendations.

Several limitations should be considered. While our CPG search was comprehensive, our search using Scopus to examine research trends and keywords may have yielded different results if conducted using another database. For CPG recommendations, it was outside of the scope of our study to grade the strength of recommendations or quality of evidence given the large number of synthesized articles, the challenge of reconciling differences in the presentation of CPG statements, and the consideration that not all CPGs quantified or specified a strength of recommendation. Clinicians should refer to the original CPGs for further guidance on the nuances of specific clinical presentations for each condition. Our choice to focus on CPG recommendations for SMT precluded our ability to examine a broader range of therapies that chiropractors may use, such as soft tissue therapies and exercise. [4]

Conclusions

Most chiropractic research articles and CPGs regarding SMT have focused on spinal pain in adults. From 1972 to 2024, research has transitioned from legal topics and case reports to randomized trials, observational studies, and evidence synthesis. We also found that there has been substantial growth in the number and rigor of standard scientific methods of chiropractic research articles over the past 50 years, resulting in multiple CPG recommendations favoring SMT. These findings reinforce the clinical utility of SMT for spine-related disorders. Additional high-quality research followed by revised CPG development is needed for understudied conditions.

Supplementary Material

File S1 Search strategies

File S2 References excluded during the full-text phase.Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.J.T., G.B. and C.M.G.;

methodology, R.J.T., G.B., R.-P.T.P., E.R.B. and C.M.G.;

software, R.J.T. and E.R.B.;

formal analysis, R.J.T., G.B. and C.M.G.;

investigation, R.J.T., G.B., R.-P.T.P. and C.M.G.;

resources, R.J.T. and E.R.B.;

data curation, R.J.T. and E.R.B.;

writing—original draft preparation, R.J.T.;

writing—review and editing, R.J.T., G.B., R.-P.T.P. and E.R.B.;

visualization, R.J.T.;

supervision, C.M.G.;

project administration, C.M.G.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Robert J. Trager reports receiving royalties from authoring two texts on the topic of sciatica. The other authors have declared no competing interests.

References:

Meeker, W.C., Haldeman, S., 2002.

Chiropractic: A Profession at the Crossroads

of Mainstream and Alternative Medicine

Annals of Internal Medicine 2002 (Feb 5); 136 (3): 216–227Harwood K.J., Pines J.M., Andrilla C.H.A., Frogner B.K.

Where to Start? A Two Stage Residual Inclusion Approach

to Estimating Influence of the Initial Provider on

Health Care Utilization and Costs for

Low Back Pain in the US

BMC Health Serv Res 2022 (May 23); 22 (1): 694Fenton J.J., Fang S.-Y., Ray M., Kennedy J., Padilla K., Amundson R., Elton D., Haldeman S., Lisi A.J., Sico J., et al.

Longitudinal Care Patterns and Utilization Among Patients

with New-Onset Neck Pain by Initial Provider Specialty

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2023 (Oct 15); 48 (20): 1409–1418Beliveau P.J.H., Wong J.J., Sutton D.A., Simon N.B., Bussières A.E., Mior S.A., French S.D.

The Chiropractic Profession: A Scoping Review of

Utilization Rates, Reasons for Seeking Care,

Patient Profiles, and Care Provided

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2017 (Nov 22); 25: 35Tindle H.A., Davis R.B., Phillips R.S., Eisenberg D.M.

Trends in Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine

by US Adults: 1997–2002.

Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2005;11:42–49.Nahin R.L., Rhee A., Stussman B.

Use of Complementary Health Approaches Overall and

for Pain Management by US Adults.

JAMA. 2024;331:613–615.

doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.26775.von Kuster T., Jr.

Chiropractic Health Care: A National Study of Cost of Education,

Service Utilization, Number of Practicing Doctors of Chiropractic,

and Other Key Policy Issues. Volumes I–II.

Foundation for the Advancement of Chiropractic Tenets and Science;

Washington, DC, USA: 1980. 353pCherkin D.C., Mootz R.D.

Chiropractic in the United States:

Training, Practice, and Research

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research,

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services;

Rockville, MD, USA: 1997. AHCPR Publication No. 98-N002.Simpson J.K.

The Five Eras of Chiropractic & the Future of Chiropractic

As Seen Through the Eyes of a Participant Observer

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2012 (Jan 19); 20 (1): 1Bigos S.J., Bowyer R., Brown K., Deyo R., Haldeman S., Hart J.L., Johnson E.W., et al.

Acute Low Back Problems in Adults:

Assessment and Treatment

Quick Reference Guide for Clinicians: Number 14

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR). 1994; 1–31United States Congress Conference Committees.

U.S. Congress . HR 1:

Social Security Amendments for 1972.

Brief Description of Senate Amendments, Prepared for the Use of the Conferees.

US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC, USA: 1972.Whedon J.M., Goertz C.M., Lurie J.D., Stason W.B.

Beyond Spinal Manipulation: Should Medicare Expand

Coverage for Chiropractic Services? A Review and

Commentary on the Challenges for Policy Makers

J Chiropractic Humanities 2013 (Aug 28); 20 (1): 9–18Pitt Launches a Doctor of Chiropractic Program.

[(accessed on 19 February 2024)]. Available online:

https://www.pitt.edu/pittwire/features-articles/pitt-

chiropractic-program-lower-back-pain.Doctor of Chiropractic|

University of Pittsburgh School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences.

[(accessed on 24 June 2024)]. Available online:

https://www.shrs.pitt.edu/chiropractic.Schut S.M.

Postgraduate Training Opportunities for Chiropractors:

A Description of United States Programs

J Chiropractic Education 2024 (Mar 4); 38 (1): 104–114Himelfarb I., Hyland J., Ouzts N., Russell M., Sterling T., Johnson C., Green B.

Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2020

National Board of Chiropractic Examiners

Greeley, CO, USA: 2020.Burton W., Salsbury S.A., Goertz C.M.

Healthcare Provider Perspectives on Integrating a Comprehensive Spine

Care Model in an Academic Health System: A Cross-Sectional Survey.

BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024;24:125.

doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-10578-z.Salsbury S.A., Goertz C.M., Twist E.J., Lisi A.J.

Integration of Doctors of Chiropractic Into Private Sector

Health Care Facilities in the United States:

A Descriptive Survey

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018 (Feb); 41 (2): 149–155Barry E.S., Merkebu J., Varpio L.

How to Conduct a State-of-the-Art Literature Review.

J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022;14:663–665.

doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-22-00704.1.Ninkov A., Frank J.R., Maggio L.A.

Bibliometrics: Methods for Studying Academic Publishing.

Perspect. Med. Educ. 2022;11:173–176.

doi: 10.1007/S40037-021-00695-4.Miake-Lye I.M., Hempel S., Shanman R., Shekelle P.G.

What Is an Evidence Map? A Systematic Review of Published

Evidence Maps and Their Definitions, Methods, and Products.

Syst. Rev. 2016;5:28.

doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0204-x.Guidelines-Standard-CINAHL.

[(accessed on 14 March 2024)]. Available online:

https://searchfilters.cadth.ca/link/76.Hollon S.D., Areán P.A., Craske M.G., Crawford K.A., Kivlahan D.R., Magnavita J.J., et al.

Development of Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014;10:213–241.

doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185529.AlRyalat S.A.S., Malkawi L.W., Momani S.M.

Comparing Bibliometric Analysis Using PubMed,

Scopus, and Web of Science Databases.

J. Vis. Exp. 2019;152:e58494.

doi: 10.3791/58494.Pozsgai G., Lövei G.L., Vasseur L., Gurr G., Batáry P., Korponai J., Littlewood N.A., et al.

Irreproducibility in Searches of Scientific Literature:

A Comparative Analysis.

Ecol. Evol. 2021;11:14658–14668.

doi: 10.1002/ece3.8154.Covidence Systematic Review Software.

Veritas Health Innovation;

Melbourne, Australia: 2024.R Core Team .

R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.

R Foundation for Statistical Computing;

Vienna, Austria: 2022.Wickham H.

Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis.

Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2016.Wickham H., Vaughan D., Girlich M.

tidyr: Tidy Messy Data.

Posit Software, PBC; Boston, MA, USA: 2024.

R Package Version 1.3.1.Aria M., Cuccurullo C.

Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis.

J. Informetr. 2017;11:959–975.

doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007.Van Eck N.J., Waltman L.

Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program

for Bibliometric Mapping.

Scientometrics. 2010;84:523–538.

doi: 10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3.Wickham H., François R., Henry L., Müller K., Vaughan D. dplyr:

A Grammar of Data Manipulation.

Posit Software, PBC; Boston, MA, USA: 2023.Kaptchuk T.J., Eisenberg D.M.

Chiropractic: Origins, Controversies, and Contributions

Archives of Internal Medicine 1998 (Nov 9); 158 (20): 2215–2224Jagbandhansingh M.P.

Most Common Causes of Chiropractic Malpractice Lawsuits.

J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 1997;20:60–64.Rubinstein S.M., de Zoete A., van Middelkoop M., Assendelft W.J.J.

Benefits and Harms of Spinal Manipulative Therapy for the Treatment

of Chronic Low Back Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

of Randomised Controlled Trials

British Medical Journal 2019 (Mar 13); 364: 1689Carpenter J., Gass M.L., Maki P.M., Newton K.M., Pinkerton J.V., Taylor M., Utian W.H.

Nonhormonal Management of Menopause-Associated Vasomotor Symptoms:

2015 Position Statement of The North American Menopause Society.

Menopause. 2015;22:1155.

doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000546.Alperovitch-Najenson D., Becker A., Belton J., Buchbinder R., Cadmus E.O., et al.

WHO Guideline for Non-Surgical Management of Chronic Primary

Low Back Pain in Adults in Primary and Community Care Settings.

World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2023.Bier J.D., Scholten-Peeters W.G.M., Staal J.B., Pool J., van Tulder M.W.

Clinical Practice Guideline for Physical Therapy Assessment

and Treatment in Patients With Nonspecific Neck Pain.

Phys. Ther. 2018;98:162–171.

doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzx118.Blanpied P.R., Gross A.R., Elliott J.M., Devaney L.L., Clewley D., Walton D.M., et al.

Neck Pain: Revision 2017: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association.

J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2017;47:A1–A83.

doi: 10.2519/jospt.2017.0302.Bryans R., Decina P., Descarreaux M., Duranleau M., Marcoux H., Potter B., Ruegg R.P.

Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Chiropractic

Treatment of Adults With Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2014 (Jan); 37 (1): 42–63Bussieres A.E., Stewart G., al-Zoubi F., Decina P., Descarreaux M., Haskett D., et al.

Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Other Conservative Treatments

for Low Back Pain: A Guideline From the Canadian

Chiropractic Guideline Initiative

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018 (May); 41 (4): 265–293Bussières A.E., Stewart G., Al-Zoubi F., Decina P., Descarreaux M., Hayden J., et al.

The Treatment of Neck Pain-Associated Disorders

and Whiplash-Associated Disorders:

A Clinical Practice Guideline

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Oct); 39 (8): 523–564Chou R., Côté P., Randhawa K., Torres P., Yu H., Nordin M., Hurwitz E.L., Haldeman S.

The Global Spine Care Initiative: Applying Evidence-Based Guidelines

on the Non-Invasive Management of Back and Neck Pain

to Low-and Middle-Income Communities.

Eur. Spine J. 2018;27:851–860.

doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5433-8.Côté P., Yu H., Shearer H.M., Randhawa K., Wong J.J., Mior S., Ameis A., et al.

Non-pharmacological Management of Persistent Headaches Associated

with Neck Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the Ontario

Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration

European Journal of Pain 2019 (Jul); 23 (6): 1051–1070Dowell D., Ragan K.R., Jones C.M., Baldwin G.T., Chou R.

CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain—United States, 2022.

MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2022;71:1–95.

doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1.Globe G., Farabaugh R.J., Hawk C., Morris C.E., Baker G., Whalen W.M.

Clinical Practice Guideline: Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2016 (Jan); 39 (1): 1–22Hawk C., Amorin-Woods L., Evans M.W., Whedon J.M., Daniels C.J., Williams R.D., et al.

The Role of Chiropractic Care in Providing Health Promotion

and Clinical Preventive Services for Adult Patients with

Musculoskeletal Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline

J Altern Complement Med 2021 (Oct); 27 (10): 850–867Hawk C., Schneider M.J., Haas M., Katz P., Dougherty P., Gleberzon B., Killinger L.Z., Weeks J.

Best Practices for Chiropractic Care for Older Adults:

A Systematic Review and Consensus Update

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2017 (May); 40 (4): 217–229Hawk C., Whalen W., Farabaugh R.J., Daniels C.J., Minkalis A.L., Taylor D.N., et al.

Best Practices for Chiropractic Management of Patients with

Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline

J Altern Complement Med 2020 (Oct); 26 (10): 884–901Hegmann K.T., Travis R., Andersson G.B.J., Belcourt R.M., Carragee E.J., et al.

Non-Invasive and Minimally Invasive

Management of Low Back Disorders

J Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2020 (Mar); 62 (3): e111–e138Kawakami M., Takeshita K., Inoue G., Sekiguchi M., Fujiwara Y., Hoshino M., et al.

Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) Clinical Practice

Guidelines on the Management of Lumbar Spinal

Stenosis, 2021—Secondary Publication.

J. Orthop. Sci. 2023;28:46–91.

doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2022.03.013.Keating G., Hawk C., Amorin-Woods L., Amorin-Woods D., Vallone S., Farabaugh R., et al.

Clinical Practice Guideline for Best Practice Management

of Pediatric Patients by Chiropractors:

Results of a Delphi Consensus Process

Integr Complement Med 2024 (Mar); 30 (3): 216–232Kjaer P., Kongsted A., Hartvigsen J., Isenberg-Jørgensen A., Schiøttz-Christensen B., et al.

National Clinical Guidelines for Non-surgical Treatment

of Patients with Recent Onset Neck Pain

or Cervical Radiculopathy

European Spine Journal 2017 (Sep); 26 (9): 2242–2257Kreiner D.S., Matz P., Bono C.M., Cho C.H., Easa J.E., Ghiselli G., Ghogawala Z., et al.

Guideline Summary Review: An Evidence-Based Clinical Guideline

for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain.

Spine J. 2020;20:998–1024.

doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2020.04.006.Kreiner D.S., Hwang S.W., Easa J.E., Resnick D.K., Baisden J.L., Bess S., Cho C.H., et al.

An Evidence-Based Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and

Treatment of Lumbar Disc Herniation with Radiculopathy.

Spine J. 2014;14:180–191.

doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.08.003.Kreiner D.S., Shaffer W.O., Baisden J.L., Gilbert T.J., Summers J.T.

An Evidence-Based Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and

Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (Update)

Spine J. 2013;13:734–743.

doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.11.059.Lisi A.J., Salsbury S.A., Hawk C., Vining R.D., Wallace R.B., Branson R., Long C.R.

Chiropractic Integrated Care Pathway for

Low Back Pain in Veterans: Results of

a Delphi Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018 (Feb); 41 (2): 137–148Macfarlane G.J., Kronisch C., Dean L.E., Atzeni F., Häuser W., Fluß E., et al.

EULAR Revised Recommendations for the Management of Fibromyalgia.

Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017;76:318–328.

doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724.Ma K., Zhuang Z.-G., Wang L., Liu X.-G., Lu L.-J., Yang X.-Q., Lu Y., et al.

The Chinese Association for the Study of Pain (CASP):

Consensus on the Assessment and Management of

Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain.

Pain Res. Manag. 2019;2019:e8957847.

doi: 10.1155/2019/8957847.Matz P.G., Meagher R.J., Lamer T., Tontz W.L., Annaswamy T.M., Cassidy R.C., et al.

Guideline Summary Review: An Evidence-Based Clinical

Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of

Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis.

Spine J. 2016;16:439–448.

doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.11.055.National Guideline Centre (UK)

Low Back Pain and Sciatica in over 16s:

Assessment and Management

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE);

London, UK: 2016.National Guideline Centre (UK)

Low Back Pain and Sciatica in over 16s:

Assessment and Management

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE);

London, UK: 2020.

Qaseem A., Wilt T.J., McLean R.M., Forciea M.A.

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic

Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From

the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Stochkendahl M.J., Kjaer P., Hartvigsen J., Kongsted A., Aaboe J., et al.

National Clinical Guidelines for Non-Surgical Treatment of

Patients with Recent Onset Low Back Pain or

Lumbar Radiculopathy.

Eur. Spine J. 2018;27:60–75.

doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5099-2.Weis C.A., Pohlman K., Barrett J., Clinton S., da Silva-Oolup S., et al.

Best-Practice Recommendations for Chiropractic Care

for Pregnant and Postpartum Patients:

Results of a Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2022 (Sep); 45 (7): 469–489Whalen W., Farabaugh R.J., Hawk C., Minkalis A.L., Lauretti W.

Best-Practice Recommendations for Chiropractic Management

of Patients With Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 635–650Whalen W.M., Hawk C., Farabaugh R.J., Daniels C.J., Taylor D.N., Anderson K.R.

Best Practices for Chiropractic Management of Adult Patients With

Mechanical Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline

for Chiropractors in the United States

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2022 (Oct); 45 (8): 551-565Yu H., Côté P., Wong J.J., Shearer H.M., Mior S., Cancelliere C., et al.

Noninvasive Management of Soft Tissue Disorders of the Shoulder:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the Ontario Protocol for

Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration

European J Pain 2021 (Sep); 25 (8): 1644–1667Weis C.A., Stuber K., Murnaghan K., Wynd S.

Adverse Events From Spinal Manipulations in the Pregnant

and Postpartum Periods: A Systematic Review and Update

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2021 (Apr); 65 (1): 32–49Trager R.J., Dusek J.A.

Chiropractic Case Reports: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis.

Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2021;29:17.

doi: 10.1186/s12998-021-00374-5.Whedon J.M., Petersen C.L., Schoellkopf W.J., Haldeman S.

The Association Between Cervical Artery Dissection

and Spinal Manipulation Among US Adults

European Spine J 2023 (Oct); 32 (10): 3497–3504Whedon J.M., Petersen C.L., Li Z., Schoelkopf W.J., Haldeman S.

Association Between Cervical Artery Dissection and Spinal

Manipulative Therapy - A Medicare Claims Analysis

BMC Geriatrics 2022 (Nov 29); 22 (1): 917Church E.W., Sieg E.P., Zalatimo O., Hussain N.S., Glantz M., Harbaugh R.E.

Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Chiropractic Care and

Cervical Artery Dissection: No Evidence for Causation

Cureus 2016 (Feb 16); 8 (2): e498Swait G., Finch R.

What Are the Risks of Manual Treatment of the Spine?

A Scoping Review for Clinicians

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2017 (Dec 7); 25: 37Chu E.C.-P., Trager R.J., Lee L.Y.-K., Niazi I.K.

A Retrospective Analysis of the Incidence of

Severe Adverse Events Among Recipients of

Chiropractic Spinal Manipulative Therapy

Sci Rep 2023 (Jan 23); 13 (1): 1254Farabaugh R., Hawk C., Taylor D., Daniels C., Noll C., Schneider M., McGowan J., et al.

Cost of Chiropractic Versus Medical Management of

Adults with Spine-related Musculoskeletal Pain:

A Systematic Review

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2024 (Mar 6); 32: 8Trager R.J., Cupler Z.A., Srinivasan R., Casselberry R.M., Perez J.A., Dusek J.A.

Association between Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation and Gabapentin

Prescription in Adults with Radicular Low Back Pain:

Retrospective Cohort Study Using US Data.

BMJ Open. 2023;13:e073258.

doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-073258.Kazis L.E., Ameli O., Rothendler J., Garrity B., Cabral H., McDonough C., et al.

Observational Retrospective Study of the Association of

Initial Healthcare Provider for New-onset Low Back Pain

with Early and Long-term Opioid Use

BMJ Open. 2019 (Sep 20); 9 (9): e028633Trager R.J., Gliedt J.A., Labak C.M., Daniels C.J., Dusek J.A.

Association Between Spinal Manipulative Therapy and

Lumbar Spine Reoperation After Discectomy:

A Retrospective Cohort Study

BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2024 (Jan 10); 25 (1): 46Trager R.J., Cupler Z.A., Srinivasan R., Casselberry R.M., Perez J.A., Dusek J.A.

Chiropractic Spinal Manipulation and Likelihood of Tramadol

Prescription in Adults with Radicular Low Back Pain:

A Retrospective Cohort Study Using US Data.

BMJ Open. 2024;14:e078105.

doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-078105.Côté P., Negrini S., Donzelli S., Kiekens C., Arienti C., Ceravolo M.G., et al.

Introduction to Target Trial Emulation in Rehabilitation:

A Systematic Approach to Emulate a Randomized

Controlled Trial Using Observational Data.

Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2024;60:145–153.

doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.24.08435-1.Listl S., Jürges H., Watt R.G.

Causal Inference from Observational Data.

Community Dent.

Oral Epidemiol. 2016;44:409–415.

doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12231.Trager R.J., Baumann A.N., Rogers H., Tidd J., Orellana K., Preston G., Baldwin K.

Efficacy of Manual Therapy for Sacroiliac Joint Pain Syndrome:

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

of Randomized Controlled Trials.

J. Man. Manip. Ther. 2024;103:e39117.

doi: 10.1080/10669817.2024.2316420.Pershing M., Hirekhan O., Syed A., Elliott J.O., Toot J.

Documentation of International Classification of Headache

Disorders Criteria in Patient Medical Records:

A Retrospective Cohort Analysis.

Cureus. 2024;16:e52209.

doi: 10.7759/cureus.52209.Minen M.T., Lindberg K., Wells R.E., Suzuki J., Grudzen C., Balcer L., Loder E.

Survey of Opioid and Barbiturate Prescriptions in

Patients Attending a Tertiary Care Headache Center.

Headache. 2015;55:1183–1191.

doi: 10.1111/head.12645.Moore C., Adams J., Leaver A., Lauche R., Sibbritt D.

The Treatment of Migraine Patients Within Chiropractic:

Analysis of a Nationally Representative

Survey of 1869 Chiropractors

BMC Complement Altern Med 2017 (Dec 4); 17 (1): 519Rist P.M., Hernandez A., Bernstein C., Kowalski M., Osypiuk K., Vining R., Long C.R.

The Impact of Spinal Manipulation on Migraine Pain and

Disability: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Headache: J Head and Face Pain. 2019 (Apr); 59 (4): 532–542Wayne P.M.

Chiropractic Care for Episodic Migraine.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital; Boston, MA, USA: 2024.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT06229834.Schneider M.J., Ammendolia C., Murphy D.R., Glick R.M., Hile E., Tudorascu D.L.

Comparative Clinical Effectiveness of Nonsurgical Treatment

Methods in Patients With Lumbar Spinal Stenosis:

A Randomized Clinical Trial

JAMA Netw Open 2019 (Jan 4); 2 (1): e186828

Return to GUIDELINES

Since 10-23-2024

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |