Best Practices for Chiropractic Management of

Adult Patients With Mechanical Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline for

Chiropractors in the United StatesThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2022 (Oct); 45 (8): 551-565 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Wayne M. Whalen, DC • Cheryl Hawk, DC, PhD • Ronald J. Farabaugh, DC • Clinton J. Daniels, DC, MS

David N. Taylor, DC • Kristian R. Anderson, DC • Louis S. Crivelli, DC, MS • Derek R. Anderson, PhD

Lisa M. Thomson, DC • Richard L. Sarnat, MD

Clinical Sciences,

Texas Chiropractic College,

Pasadena, Texas.

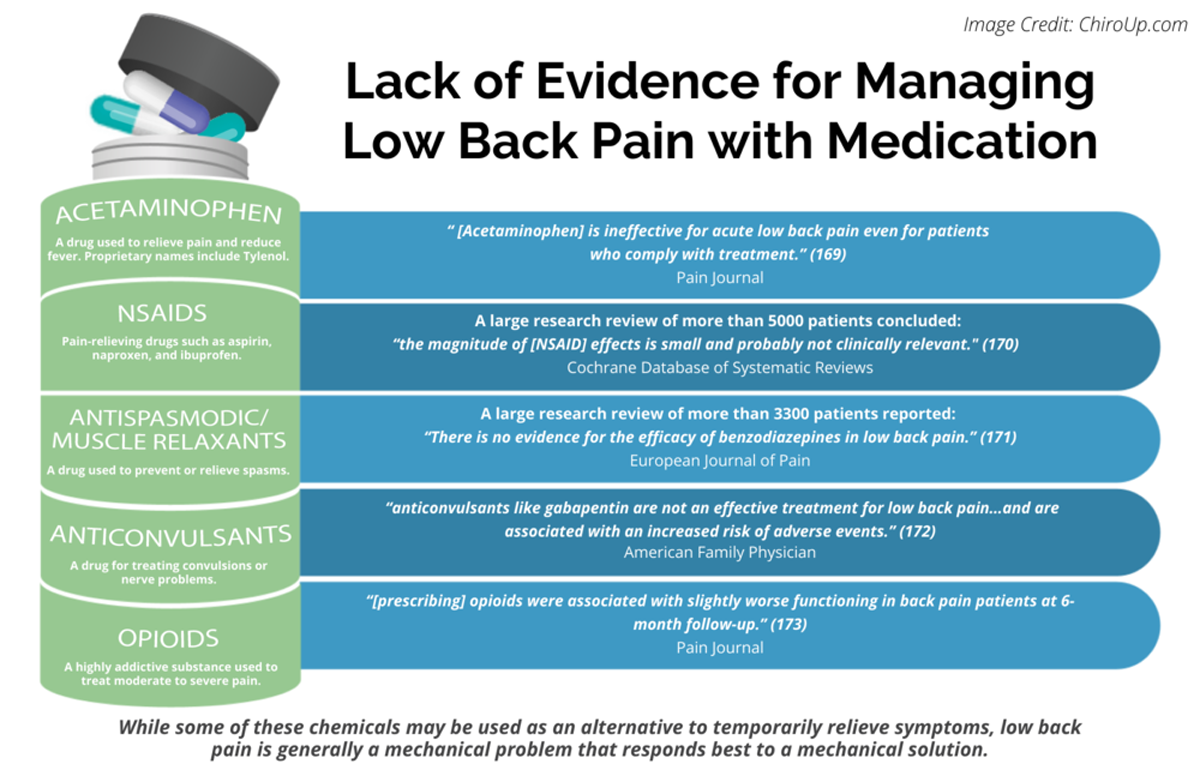

FROM: Pain 2019 (Dec)

FROM: Cochrane Database 2020 (Apr)

FROM: European Journal of Pain 2017 (Feb)

FROM: American Family Physician 2019 (Mar 15)

FROM: PAIN 2013 (Jul)Objective: The purpose of this paper was to update the previously published 2016 best-practice recommendations for chiropractic management of adults with mechanical low back pain (LBP) in the United States.

Methods: Two experienced health librarians conducted the literature searches for clinical practice guidelines and other relevant literature, and the investigators performed quality assessment of included studies. PubMed was searched from March 2015 to September 2021. A steering committee of 10 experts in chiropractic research, education, and practice used the most current relevant guidelines and publications to update care recommendations. A panel of 69 experts used a modified Delphi process to rate the recommendations.

Results: The literature search yielded 14 clinical practice guidelines, 10 systematic reviews, and 5 randomized controlled trials (all high quality). Sixty-nine members of the panel rated 38 recommendations. All but 1 statement achieved consensus in the first round, and the final statement reached consensus in the second round. Recommendations covered the clinical encounter from history, physical examination, and diagnostic considerations through informed consent, co-management, and treatment considerations for patients with mechanical LBP.

Conclusion: This paper updates a previously published best-practice document for chiropractic management of adults with mechanical LBP.

Keywords: Low Back Pain; Manipulation, Chiropractic; Manipulation, Orthopedic; Manipulation, Osteopathic; Musculoskeletal Manipulations.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is the leading cause of disability in the United States (US) and exacts an expensive toll on society and individuals. [1] Globally, as of 2015, more than half a billion people had LBP. [2] There are many approaches to the evaluation and treatment of LBP, with varying risks and outcomes. Appropriate clinical interventions using an evidence-based approach are believed to provide better and more cost-effective care. [3] As of 2017, there were an estimated 77,000 practicing chiropractors in the US. Doctors of chiropractic (DC) use a conservative, non-surgical, and non-pharmaceutical approach to care for patients with LBP. [4] Due to the unique practice approaches of DCs in the US, an accurate and up-to-date guideline is necessary to inform current US chiropractors of best practices. Because the evidence continues to change, the purpose of this project was to update the clinical practice guideline previously published in 2016. [4]

Methods

Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Texas Chiropractic College. Panelists who participated consented to participate in the consensus process and for their names to be included in the publication.

Steering Committee

The Steering Committee (SC) consisted of clinicians and academicians with clinical and research experience with LBP. Their responsibilities were to examine and evaluate new evidence, develop recommendations based on the best available evidence, revise past recommendations based on the panelists’ ratings and comments to reach consensus, and update the recommendations.

The SC consisted of 8 DCs, some of whom had additional training in massage and nursing, a psychologist (PhD) who had experience with patients experiencing chronic pain in the Veterans Administration, and a medical physician with experience working with patients with musculoskeletal pain. Six members were in private practice: 2 in the Veterans Administration as clinicians and 2 in health care training institutions. Five DCs were in Clinical Compass leadership positions. The Clinical Compass (formerly the Council on Chiropractic Guidelines and Practice Parameters) is a chiropractic organization that represents US state and national chiropractic associations and the US chiropractic colleges.

Literature Search

A health sciences librarian conducted 2 literature searches, and 2 investigators screened the articles for inclusion.Search 1

To identify seed documents, we conducted a search of PubMed for publications after the literature search from our 2016 guideline (03/01/2015) for clinical practice guidelines (CPG) for non-drug, non-surgical management of LBP in adults. [4] The inclusion criteria were as follows: publications from March 1, 2015, to September 1, 2021; English language; non-drug, non-surgical interventions for mechanical LBP in adults; and CPGs. Exclusion criteria were any populations other than non-pregnant adults; only 1 sex included; and restricted to specific local populations or geographic areas (see Supplementary Data for search strategy). We reviewed citations in first-stage documents, and the SC identified relevant papers that were not captured in the first search. We used the 2020 CPG on chiropractic management of adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain as a resource. [5]

Search 2

We searched for topics that were not addressed in detail in the CPGs. For systematic reviews, we used the same search strategy as Search 1 but filtered for “review.” We included systematic reviews of original studies. Randomized controlled trials were identified by reference tracking or expert recommendations. At least 2 investigators screened studies for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion until agreement was reached.Evaluation of the Quality of the Evidence

We evaluated included articles for quality. Evaluation of CPGs used the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE)–Global Rating Scale. [6] Systematic reviews and randomized trials used the modified Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network checklists. [7] We did not assess the quality of other types of studies; we only identified designs and categorized them as lower level. At least 2 investigators rated each study and discussed differences in ratings until they reached agreement; if they could not reach agreement, a third investigator rated the study to break the tie. Cohort studies, narrative reviews, government reports, books, etc, were not evaluated for quality but categorized as lower-level evidence.

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) to assess the overall quality of the supporting evidence for the seed statements. [8, 9] At least 3 investigators performed the GRADE assessment independently. If they disagreed, they resolved the rating by discussion (see Supplementary Data for GRADE rating).

Strength of Recommendations

We used the strength of recommendations (SoR). [10–12] Recommendations were either graded as strong (SoR = 1) or weak (SoR = 2). At least 3 investigators rated the SoR, and if they did not agree, they discussed the differences until agreement was reached.

Seed Statement Development

The 2016 CPG was used as the seed document, [4] and 2 CPGs [5, 13] were used to revise the seed statements. The SC used an iterative process with revisions, as it related to chiropractic practice in the US.

Consensus Panel

We invited panelists of various disciplines who were experienced in providing care for adults with LBP. Nominees were invited after review and approval by the SC. The consensus panel included a panel of DCs and other health professionals representing practice and academic experience. The panel characteristics may be found in the Supplementary Data.

The Modified Delphi Process

The consensus panel reviewed the previous clinical practice guideline (CPG) [4] and updated seed statements and references. The consensus process was conducted via email. Panelists were de-identified during the rating process to reduce bias. After each round of review, the SC revised statements based on the panelists’ ratings and comments. Only items on which there was disagreement were re-circulated. We used the RAND-UCLA methodology for rating the appropriateness using an ordinal scale of 1 to 9 (highly inappropriate to highly appropriate) to each seed statement. [14] Panelists were emailed a form with each seed statement, the ordinal scale, and a place to make comments. “Appropriateness” was defined as the patient's expected health benefit being greater than any expected negative consequences by a sufficiently wide margin that it is worth doing without considering cost. We instructed panelists that if they rated a statement as inappropriate (rating 1–3) to provide a reason and a citation from the peer-reviewed literature to support it, if available. Without a reason or citation, the response was considered incomplete and considered a missing value.

Data Analysis

The project coordinator entered all ratings into an SPSS file for median rating and percent agreement. Comments were organized by panelist number and statement number and rating. All ratings and comments remained identified only by a number when circulated to the panelists and the SC. They received the median rating, percent agreement, and comments for each statement. Any statements not reaching 80% agreement were revised by the SC based on the panelists’ comments and were recirculated until the panel reached at least 80% agreement.

Stakeholder Engagement and External Review

We disseminated the seed statements and methods to promote transparency and stakeholder involvement in guideline development. The consensus panel included stakeholders, and we invited public comments using methods we developed for previous projects. [5, 13]

Consensus Rounds

Two modified Delphi consensus rounds were conducted; all 69 panelists completed both. For Round 1, all of the 38 statements but 1 had a mean rating of >80% (median rating = 9 on a 0–9 scale). One statement had a mean percent agreement of <80% (78%). Three statements had a mean percent agreement <90% but were also >80% (84%, 86%, 88%). We conducted Round 2 with the 1 statement not reaching 80% consensus after analyzing the panelists’ comments and revising accordingly. In Round 2, consensus was reached on that statement (mean percent agreement = 87%).

Public Comments

During the comment period (April 2, 2022, to May 2, 2022), an internet link was posted on Facebook (Meta) soliciting comments. We received 30 comments from 6 people; 4 were DCs, 1 was an RN/PhD, and 1 was anonymous. The SC carefully considered all comments and incorporated relevant ones into the final manuscript for purposes of clarification.

Results

Figure 1

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Figure 2

page 6Review and Assessment

Literature Search Results

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the primary literature search. The second search for systematic reviews yielded 138 results, with additional hand search/expert recommendations adding 15 for a total of 153 citations, of which 143 were excluded, leaving 10 systematic reviews. Five randomized trials were identified through reference tracking.

Quality Assessment

Table 1 lists the 14 CPGs included: 12 were rated high-quality using the AGREE–Global Rating Scale [15–25] or AGREE-II, [4, 26] and 2 were not rated because they were used as background/seed documents and were developed by the group involved in the current study. [5, 13]

Table 2 lists the 10 systematic reviews included; all were rated high-quality [27–33] or acceptable-quality. [34–36]

Table 3 lists the 5 randomized controlled trials included; all were rated high-quality. [37–41]

Key Terminology and/or Definitions

Figure 2 lists important terms and definitions related to LBP management, including specific classifications of LBP-related terms. [13, 21, 30, 36, 42–50]

Best Practices for Chiropractic Management of Adult Patients With Mechanical LBP in the US

Informed Consent, Risks, and Benefits: IC1.

Informed consent should include direct communication between the doctor and the patient. The DC should explain all procedures, including examination, diagnosis, and treatment/no treatment options, clearly and in terms the patient understands. Explain both benefits and risks. [4] Ask the patient if they have any questions; answer the questions and confirm that the patient understands all information communicated. Understanding is essential to shared decision-making. [4] Record the discussion and patient’s consent or declination of treatment in the health record. [51–53] (Quality D, SoR 1)

Informed Consent, Risks, and Benefits: IC2

Adhere to local/regional/national legal requirements. Seek advice on compliance from the appropriate authority (eg, malpractice carrier or professional association). (Quality D, SoR 1)

History, Examination, and Special Tests

Diagnostic Considerations for LBP: LB1

The DC should establish a management plan using relevant evidence based on history, physical examination findings that support a working diagnosis, and differential diagnoses. [17, 21, 22, 32, 54] (Quality B, SoR 1)

Diagnostic Considerations for LBP: LB2

For patients with new episodes of LBP, consider risk stratification for assessing outcomes (eg, STarT Back risk assessment tool). [55] Management strategies using fewer targeted modalities and procedures may be more appropriate for low-risk patients, and more intensive targeted treatments for those at higher risk for poor outcomes (eg, multiple therapies, including mind-body approaches, and active therapies are generally favored over passive ones). [22, 55–57] (Quality B, SoR 1)

History: H1

Because psychosocial factors influence pain, ask patients about factors that might delay recovery or amplify pain (eg, mood or sleep disorders, work-related factors [49, 50]) and helpful factors (eg, positive coping skills and social support). [32, 49, 50, 54] (Quality B, SoR 2)

History: H2

Obtain a thorough history of the pain symptoms, previous and concurrent treatment, and psychosocial factors to develop an appropriate chiropractic management plan for patients with acute and chronic pain. [17, 56] The history should include assessment of red and yellow flags, precipitating factors, and pain characteristics. [16, 17, 19] (Quality A, SoR 1). See the Supplementary Data for additional information on obtaining a history.

History: H3

Consider “yellow flags,” which may predict poorer outcomes or prolonged recovery time.

These include concurrent conditions, psychological factors, including beliefs about illness and treatment, attitudes, emotional states, and pain behavior. [21, 56, 58, 59] (eg, [45, 58] Current compensation and claims issues, fear-avoidance behavior, lack of social support, negative affect/mood or depression, pain catastrophizing, and work-related stress). (Quality A, SoR 1)

History: H4

For patients with a new episode of LBP, consider using a risk stratification measure at the initial visit. [25, 37, 55, 57]

History: H5

Consider referral to a licensed mental health provider for patients with psychological or psychosocial complicating factors for further evaluation and/or a trial of cognitive behavioral therapy or mindfulness-based stress reduction. [21, 27, 36, 38] (Quality A, SoR 1)

History: H6

Focus the physical examination on current symptoms combined with the short and long-term health history. [21, 60] (Quality C, SoR 2)

Examination: E1

Conduct a physical examination [60] based on the symptoms and health history, including sites of primary and secondary symptoms. Assess function and pain, including relevant musculoskeletal and neuromuscular examinations. [15–17, 19, 21, 60] (Quality B, SoR 1)

Diagnostic Imaging: D1

Do not use imaging routinely to identify the pain source for LBP in the absence of red flags. Consider imaging if red flags are present, which should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis after a thorough history and examination are performed. [15, 16, 19] (Quality A, SoR 1)

Diagnostic Imaging: D2

Consider imaging patients under the following circumstances: (Quality A, SoR 1) [4, 15, 19]:(1) no improvement after a reasonable course (4–6 weeks) [23] of care;

(2) red flags on history or physical exam;

(3) severe and/or progressive neurologic deficits;

(4) severe spinal trauma; and/or

(5) suspected severe anatomical deformity.

Diagnostic Imaging: D3

Consider magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scans rather than radiographs for patients with chronic LBP who are nonresponsive to conservative care after a 4– to 6–week trial of care and/or conditions accompanied by progressive radiculopathy. [4, 19]

Conditions such as spinal stenosis, which may not be detectable with physical examination, may require magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosis. [19] (Quality A, SoR 1)

Absolute and Relative Contraindications to HVLA-SMT

Figure 3

Figure 4 Contraindications: C1.

Consider patient presentations (Figure 3) [4, 16, 61–63] that factor into clinical decision-making, which may still permit administering a trial of high-velocity, low-amplitude spinal manipulation (HVLA-SMT). Conduct a thorough history (including prior response to care), examination, and informed consent to aid their treatment rationale. Each individual should be managed on a case-by-case basis (see section on interventions). [64, 65] (Quality C, SoR 1)

Contraindications: C2.

Consider relative contraindications to HVLA-SMT. Discuss with the patient the possible risks and benefits of treatment before applying the treatment (eg, high-risk pregnancy, prior surgical intervention to the involved area, and history of cancer). [64, 65] (Quality C, SoR 1)

Contraindications: C3.

Do not administer HVLA-SMT for conditions considered absolute contraindications. These include health factors, findings, or conditions that are by nature unstable, and manipulation of the involved area may place the patient at undue risks, such as those that significantly weaken bone, neurological, or vascular structure integrity (Figure 4). [4, 17, 18, 64, 65] (Quality C, SoR 1)

Management Considerations

General Pain Management: G1.

Educate and encourage the patient to self-manage and use nondrug approaches if possible. [24, 31, 43] (Quality A, SoR 1)

General Pain Management: G2.

Co-manage patients on prescribed pain medications by collaborating with their prescribing clinician. [35, 66] (Quality A, SoR 1)

General Pain Management: G3.

Implement active interventions as early as possible and educate them to better engage patients in their care and encourage self-efficacy. [25] Passive interventions may be useful in the initial stages of patient care for pain control. [15, 43] (Quality A, SoR 1)

General Pain Management: G4.Combine passive and active interventions, particularly self-care, and include provider reassurance.

Educate the patient to use self-care, which may include home care measures such as rest, early return to tolerated activities, stretching, heat and ice, medications, and other therapeutics.

Passive approaches may includemedication by referral/co-management with a prescribing provider,

manual therapy,

massage, and

physical modalities. [28, 31, 33, 34]Active and self-care interventions may include

exercise, [25]

healthy diet, [67]

meditation, [27, 30, 36, 38]

yoga, [31] and

other lifestyle changes. (Quality B, SoR 1)

General Management: GM1.

Develop patient management decisions based on patient complaints, clinical findings, evidence-based interventions, and the best interests of the patient. Clinician philosophy/attitudes or financial considerations should not play a role in clinical care recommendations. [45] (Quality C, SoR 1)

General Management: GM2.

Provide a short trial of care to patients with acute pain. Observe if the patient’s pain and limitation of function partially or fully resolve, although recurrences may be common. [15, 17, 24, 25, 57, 68] (Quality A, SoR 1)

General Management: GM3.

Avoid providing inadequate and/or guideline-non-concordant management or delaying early clinical management, which may increase the risk of chronicity and disability. [18, 56] (Quality A, SoR 1)

General Management: GM4.

As early as possible, identify patients who may respond poorly in the acute stage and/or those with increased risk factors or concurrent complicating factors for chronicity. [15, 57] (Quality A, SoR 1)

General Management: GM5.

Work may be done independently or with a multidisciplinary team for management of pain and functional restoration for patients with acute or chronic LBP. [21, 69] (Quality A, SoR 1)

General Management: GM6.

Consider that spinal manipulation for LBP is associated with a reduced likelihood of use of opioid analgesics and adverse drug events. [3, 29, 66, 70–72] (Quality A, SoR 1)

General Management: GM7.

Consider that spinal manipulation for back pain is associated with a reduced likelihood of surgery. [73, 74] (Quality B, SoR 2)

Outcome Assessment

Table 4

Figure 5

page 9Use validated Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) to assess patient symptoms, characteristics, and to assess progress over time (Table 4 shows PROMs for acute and chronic LBP). [4, 20, 21, 45, 75] (Quality A, SoR 1)

Care Pathway

A care pathway for an adult patient with mechanical LBP is shown in Figure 5.

Considerations for frequency and duration of treatment for acute and chronic LBP are seen in Table 5. [4, 13, 39–41, 45, 76, 77]

Interventions

Figure 6 Interventions: IN1

Consider active and passive interventions (eg, physical and mind/body) in the management plan. [15, 17, 24, 78, 79] Figure 6 shows recommendations for interventions, based on current evidence. [15, 31] (Quality A, SoR 1)

Interventions: IN2

Choose appropriate active and passive interventions, with passive care being most appropriate for acute conditions but also possibly indicated for chronic LBP. Mind-body approaches and multidisciplinary rehabilitation are used for chronic LBP. [30, 36] (Quality A, SoR 1)

Discussion

This paper updates the best-practice guideline on chiropractic management of mechanical LBP in adults in the US from the prior iterations. [4, 82] This guideline provides evidence-informed guidance to DCs related to both initial care management and the progression of care throughout an episode of the condition to reduce practice variability among providers while improving outcomes. We identified benchmarks and decision points in care management and provided information related to each issue. Providers can use this document as a reference point for the care they provide their patients.

This updated Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) condensed the number of recommendations from 51 to 38 while providing more evidence-informed insight into the diagnostic considerations for LBP, including the history and examination and diagnostic imaging. This document provides a more comprehensive description of the conservative management approaches to LBP, including chiropractic approaches and co-management considerations for multidisciplinary care.

This guideline recommends self-care advice/education, multimodal care, spinal manipulation, therapeutic exercise, and collaboration with other professionals. Typically, providers are advised to provide evidence-based information on the patient's condition in terms they can understand; discuss the expected, usually benign treatment course and reassure the patient; provide appropriate condition-specific exercises; promote early return to activities; encourage healthy lifestyle choices and activities of daily living; and provide effective self-management strategies. [15, 21, 25, 80, 83, 84]

Studies suggest that patient education can reduce psychological distress associated with LBP but has little effect as a sole intervention on pain and function. [85–87] Patient education also appears to reduce imaging rates. [88] However, patients appear to be most interested in an explanation of what is wrong, how to improve their pain, and in improving their ability to return to performing daily tasks. [89]

This guideline recommends that fewer interventions be provided to low-risk patients and that more intensive targeted treatments be reserved for patients at higher risk for poor outcomes.This suggests that low-risk patients may require only minimal targeted treatment approaches, such as education, manipulation, exercise, and home care advice or perhaps the judicious use of a brief trial of passive therapies.

Patients identified with higher risk stratification might benefit from more intensive care, which might include both multi-modal treatment and co-management by other providers, including treatment such as cognitive behavioral therapy earlier in their treatment course. Therefore, patients who need more care should get more care, and those who need less should get less care.The CGP recommends that providers encourage and educate patients to assume a role in their care, engage in activities to promote self-management, and try non-drug approaches first. When patients require medications for pain, we encourage DCs to work collaboratively with the patient's prescribing provider. For example, confusion may result when a provider is encouraging a patient not to take medications that another has recommended. Instead, a dialogue between health professionals that encourages cooperation and is in the best interests of the patient should be pursued.

Strengths and Limitations

We used critical appraisal instruments and rigorous consensus methodology, in addition to performing a comprehensive literature search. Our guideline was built on the 2 prior iterations previously published and the 2020 guideline on chiropractic management of chronic musculoskeletal pain, which included chronic LBP and was based on the comprehensive Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality systematic review on that topic. [31] We included a large multidisciplinary group of experts and public input by soliciting comments from professional organizations and individuals. Furthermore, our recommendations are congruent with other recent CPGs. [15, 17, 21, 22, 24]

Our literature search was limited to papers in the English language, which may have missed other papers that should have been included in our review. While we attempted to better define terminology, including the classification of acute, subacute, and chronic LBP and relied on widely used definitions, these definitions might not have been consistent with definitions described in other CPGs. This guideline did not include a thorough discussion of education for patients with acute or chronic mechanical LBP; therefore, more detailed information about education was not included. [15, 21, 25, 80, 83, 84]

Specific contraindications related to non-HVLA manipulation interventions commonly utilized by chiropractors (eg, physiotherapeutic modalities, soft tissue mobilization, exercise) were not included in this CPG. The absence of this discussion specific to these interventions should not infer that those interventions do not have contraindications. Another limitation was that we did not discuss potential causes of LBP, such as vascular concerns that include dissecting aortic aneurysm, which is considered a medical emergency. [90, 91]

There was limited high-quality evidence on dosage for LBP treatment approaches, including spinal manipulation, exercise, and passive modalities. Therefore, this guideline makes recommendations for treatment frequency and intensity for chiropractic care based on limited evidence. However, the discussion on the topic by the contributors was robust and provided expert consensus-based guidance to stakeholders in the absence of more robust research.

The dosing regimens for therapies for patients presenting with acute, subacute, and chronic LBP were not included. Recent studies [39, 40] have suggested that maintenance care may be more effective than symptom-guided care in reducing the total number of bothersome days of LBP. Our recommendations for treatment dosage did not address maintenance care in asymptomatic patients. Given the scarcity of literature, our paper relied on expert consensus to arrive at supportable recommendations for dosing, including the small population of chronic patients who may benefit from maintenance care. Another limitation of this guideline is that the SC and panel members were largely from the US. Therefore, components of this paper might not be applicable in other regions.

Conclusion

This paper updates a previously published evidence-based guideline, which recommends that appropriate conservative management approaches emphasize active care combined with multimodal care, including spinal manipulation for adults with mechanical LBP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Cathy Evans for her expert coordination of project communications and the consensus process and also for achieving the high response rate. The authors also thank research librarians Sheryl Walters, MLS, and Claire Noll, MS, MLIS, for their expertise in conducting the literature searches and thank the following Delphi panelists for their essential contribution to development of the recommendations: Wayne Bennett, DC, DABCO; Craig Benton, DC; Derrell Blackburn, MBA, DC; Charles L. Blum, DC; Gina M. Bonavito-Larragoite, DC, FIAMA; Amanda Brown, DC; Michael S. Calhoun, DC, DACBSP; Winston Carhee, DC; Wayne H. Carr, DC, ACRB, CCSP, AFMCP; Jeffrey R. Cates, DC, MS; Matthew Coté, DC, MS; Thomas R. Cotter, DC, DACRB; Zachary A. Cupler, DC, MS; Monica Curruchich, DC, RN-BSN; John Curtin, MSS, DC, IANM; Vincent DeBono, DC; Mark D. Dehen, DC, FICC; Paul Ettlinger, DC; James E. Eubanks, MD, DC, MS; Jason T. Evans, DC, DIBCN, FIACN, ABIME, NASM; Drew Fogg, DC, MS, DACRB, Cert. MDT; David Folweiler, DC, DACRB; Jonathan Free, DC; Margaret M. Freihaut, DC; Bill Gallagher, Jr, DC; Evan M. Gwilliam, DC, MBA; Jerrell Hardison, DC; Catherine Ho, L.Ac; Wayne S. Inman, MD; Gary Alan Jacob, DC, LAc, MPH; Brian L. James, MD; Jeffrey M. Johnson, DC; Valerie Johnson, DC, DABCI, DACBN; Louis A. Kazal, Jr, MD, FAAFP; Yasmeen Khan, DC, MS, MA; Robert E. Klein, DC, FACO; Rick Louis LaMarche, DC; Lawrence Jason Larragoite, DC, FIAMA, CFMP; Robert A. Leach, DC, MS, MCHES; Duane T. Lowe, DC; Eric Luke, DC, MS; Ralph C. Magnuson, DPT; Hans W. Mohrbeck, DC; Scott A. Mooring, DC, CCSP; Mark Mulak, DC, MBA, MS, DACRB; Marcus Nynas, DC, FICC; Casey Okamoto, DC; Juli Olson, DC, DACM; Colette Peabody, MS, DC; Mariangela Penna, DC; Morgan R. Price, DC; Lindsay Rae, DC; Jeffrey W. Remsburg, DC, MS, DACRB; Christopher B. Roecker, DC, MS; Vern A. Saboe, Jr, DC, FACO; Chris Sherman, DC, MPH; Scott M. Siegel, DC, FIAMA; Charles A. Simpson, DC, DABCO; Carina A. Staab, DC, MEd; Albert Stabile, Jr, DC; Kevin Stemple, PT; Mignon Sweat, MS, DC; Robert J. Trager, DC; Jason Weber, DC, DACRB; Susan Wenberg, DC, MA; John S. Weyand, DC, DABCO; Clint J. Williamson, DC; Brent Young, DC; Morgan Young, DC.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

The NCMIC Foundation provided funding for the project director and the Clinical Compass provided funding for the project coordinator. No conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): W.M.W., C.H., R.J.F., C.J.D., L.S.C.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): W.M.W., C.H., R.J.F., C.J.D.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): W.M.W., C.H., R.J.F., C.J.D., D.N.T.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): W.M.W., C.H., R.J.F., C.J.D., L.S.C.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): W.M.W., C.H., J.R.F., C.J.D., K.R.A., D.A.

Literature search (performed the literature search): W.M.W., C.H., R.J.F., C.J.D., D.N.T.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): W.M.W., C.H., R.J.F., C.J.D., D.N.T.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): W.M.W., C.H., R.J.F., C.J.D., R.L.S., D.N.T., D.A., K.R.A., L.S.C., L.M.T.

Other (list other specific novel contributions) Quality assessment of literature: W.W., C.H., R.F., C.D., K.A., D.N.T., L.M.T., L.S.C.

References:

Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML. et al.

What Low Back Pain Is and Why We Need to Pay Attention

Lancet. 2018 (Jun 9); 391 (10137): 2356–2367

This is the second of 4 articles in the remarkable Lancet Series on Low Back PainHurwitz EL Randhawa K Yu H Cote P Haldeman S

The Global Spine Care Initiative: A Summary of the

Global Burden of Low Back and Neck Pain Studies

European Spine J 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 796–801Whedon JM Kizhakkeveettil A Toler AW et al.

Initial Choice of Spinal Manipulation Reduces Escalation of Care

for Chronic Low Back Pain Among Older Medicare Beneficiaries

Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2022 (Feb 15); 47 (4): E142–E148Globe G., Farabaugh R.J., Hawk C., Morris C.E., Baker G., Whalen W.M., Walters S., et al

Clinical Practice Guideline: Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jan); 39 (1): 1–22Hawk C, Whalen W, Farabaugh RJ, et al.

Best Practices for Chiropractic Management of Patients with

Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline

J Altern Complement Med 2020 (Oct); 26 (10): 884–901Brouwers MC Kho ME Browman GP et al.

The Global Rating Scale complements the AGREE II in

advancing the quality of practice guidelines.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2012; 65: 526-534Harbour R Lowe G Twaddle S

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network:

the first 15 years (1993-2008).

J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2011; 41: 163-168Guyatt GH Oxman AD Kunz R et al.

Going from evidence to recommendations.

BMJ. 2008; 336: 1049-1051Guyatt GH Oxman AD Vist GE et al.

GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence

and strength of recommendations.

BMJ. 2008; 336: 924-926Atkins D Best D Briss PA et al.

Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.

BMJ. 2004; 328: 1490Brozek JL Akl EA Alonso-Coello P et al.

Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in clinical

practice guidelines. Part 1 of 3. An overview of the GRADE approach

and grading quality of evidence about interventions.

Allergy. 2009; 64: 669-677Brozek JL Akl EA Jaeschke R et al.

Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in clinical

practice guidelines: Part 2 of 3. The GRADE approach to grading

quality of evidence about diagnostic tests and strategies.

Allergy. 2009; 64: 1109-1116Cheryl Hawk, Lyndon Amorin-Woods, Marion W Evans, James M Whedon, et. al.

The Role of Chiropractic Care in Providing Health Promotion

and Clinical Preventive Services for Adult Patients with

Musculoskeletal Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline

J Altern Complement Med 2021 (Oct); 27 (10): 850–867Fitch K Bernstein SJ Aquilar MS et al.

The RAND UCLA Appropriateness Method User's Manual.

RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA 2003Bussieres AE, Stewart G, Al-Zoubi F, Decina P, Descarreaux M, et al.

Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Other Conservative Treatments

for Low Back Pain: A Guideline From the Canadian

Chiropractic Guideline Initiative

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018 (May); 41 (4): 265–293Finucane LM Downie A Mercer C et al.

International framework for red flags for potential serious spinal pathologies.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020; 50: 350-372Haldeman S, Johnson CD, Chou R, Nordin M, Côté P, Hurwitz EL et al.

The Global Spine Care Initiative: Care Pathway

for People With Spine-related Concerns

European Spine J 2018 (Sep); 27 (Suppl 6): 901–914Hegmann KT, Travis R, Andersson GBJ, et al.

Non-Invasive and Minimally Invasive Management of Low Back Disorders

J Occup Environ Med. 2020 (Mar); 62 (3): e111–e138Hegmann KT Travis R Belcourt RM et al.

Diagnostic tests for low back disorders.

J Occup Environ Med. 2019; 61: e155-e168Kroenke K Krebs EE Turk D et al.

Core outcome measures for chronic musculoskeletal pain research:

recommendations from a Veterans Health administration work group.

Pain Med. 2019; 20: 1500-1508Lisi AJ Salsbury SA Hawk C et al.

Chiropractic Integrated Care Pathway for Low Back Pain in Veterans:

Results of a Delphi Consensus Process

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018 (Feb); 41 (2): 137–148National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE):

Low Back Pain and Sciatica in Over 16s: Assessment and Management (PDF)

NICE Guideline, No. 59 2016 (Nov): 1–1067Patel ND Broderick DF Burns J et al.

ACR appropriateness criteria low back pain.

J Am Coll Radiol. 2016; 13: 1069-1078Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA;

Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530Stochkendahl MJ, Kjaer P, Hartvigsen J et al.

National Clinical Guidelines for Non-surgical Treatment of Patients

with Recent Onset Low Back Pain or Lumbar Radiculopathy

European Spine Journal 2018 (Jan); 27 (1): 60–75Lin I Wiles LK Waller R et al.

Poor overall quality of clinical practice guidelines

for musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review.

Br J Sports Med. 2018; 52: 337-343Bahnamiri FA NA Reskati MH Hamzeh S Hosseini

Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on pain intensity

in patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review.

Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2021; 14e102509Clijsen R Brunner A Barbero M Clarys P Taeymans J

Effects of low-level laser therapy on pain in patients with

musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017; 53: 603-610Corcoran KL, Bastian LA, Gunderson CG, et al.

Association Between Chiropractic Use and Opioid Receipt Among

Patients with Spinal Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Pain Medicine 2020 (Feb 1); 21 (2): e139–e145Petrucci G Papalia GF Russo F et al.

Psychological approaches for the integrative care of chronic low back pain:

a systematic review and metanalysis.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19: 60Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, Turner JA, Friedly JL, et al.

Noninvasive Nonpharmacological Treatment for Chronic Pain:

A Systematic Review Update

Comparative Effectiveness Review Number 227

Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2020)Vining R, Shannon Z, Minkalis A, Twist E.

Current Evidence for Diagnosis of Common Conditions Causing Low Back Pain:

Systematic Review and Standardized Terminology Recommendations

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 651–664Wu LC Weng PW Chen CH Huang YY Tsuang YH Chiang CJ

Literature review and meta-analysis of transcutaneous electrical

nerve stimulation in treating chronic back pain.

Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018; 43: 425-433Almeida CC Silva V Junior GC Liebano RE Durigan JLQ.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and interferential current

demonstrate similar effects in relieving acute and chronic pain:

a systematic review with meta-analysis.

Braz J Phys Ther. 2018; 22: 347-354Kamper SJ Apeldoorn AT Chiarotto A et al.

Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic

low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis.

BMJ. 2015; 350: h444Smith SL Langen WH

A systematic review of mindfulness practices for

improving outcomes in chronic low back pain.

Int J Yoga. 2020; 13: 177-182Barone Gibbs B Hergenroeder AL Perdomo SJ Kowalsky RJ Delitto A Jakicic JM

Reducing sedentary behaviour to decrease chronic low back pain:

the stand back randomised trial.

Occup Environ Med. 2018; 75: 321-327Cherkin DC Sherman KJ Balderson BH et al.

Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive

behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and

functional limitations in adults with chronic

low back pain: a randomized clinical trial.

JAMA. 2016; 315: 1240-1249Eklund A, Hagberg J, Jensen I, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kongsted A, Lovgren P, et al.

The Nordic Maintenance Care Program: Maintenance Care Reduces

the Number of Days With Pain in Acute Episodes and Increases

the Length of Pain Free Periods for Dysfunctional Patients

With Recurrent and Persistent Low Back Pain -

A Secondary Analysis of a Pragmatic

Randomized Controlled Tial

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2020 (Apr 21); 28: 19Eklund, A., I. Jensen, M. Lohela-Karlsson, J. Hagberg, C. Leboeuf-Yde, et al. (2018).

The Nordic Maintenance Care Program: Effectiveness of Chiropractic

Maintenance Care Versus Symptom-guided Treatment for Recurrent

and Persistent Low Back Pain - A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial

PLoS One. 2018 (Sep 12); 13 (9): e0203029Haas M, Vavrek D, Peterson D, Polissar N, Neradilek MB.

Dose-response and Efficacy of Spinal Manipulation for Care of

Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Spine J. 2014 (Jul 1); 14 (7): 1106–1116Gatchel RJ Reuben DB Dagenais S et al.

Research agenda for the prevention of pain and its impact:

report of the Work Group on the Prevention of Acute and

Chronic Pain of the Federal Pain Research Strategy.

J Pain. 2018; 19: 837-851Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health.

National Pain Strategy: A Comprehensive Population

Health-Level Strategy for Pain

Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services,

National Institutes of Health; 2016.Treede RD Rief W Barke A et al.

A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11.

Pain. 2015; 156: 1003-1007Whalen W, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, et al.

Best-Practice Recommendations for Chiropractic

Management of Patients With Neck Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 635–650Nijs J, Apeldoorn A, Hallegraeff H, et al.

Low Back Pain: Guidelines for the Clinical Classification of

Predominant Neuropathic, Nociceptive, or Central Sensitization Pain

Pain Physician. 2015 (May); 18 (3): E333–346Crawford C Lee C Freilich D

Active Self-Care Therapies for Pain Working Group.

Effectiveness of active self-care complementary and integrative

medicine therapies: options for the management of

chronic pain symptoms.

Pain Med. 2014; 15: S86-S95Bigos S, Bower O, Braen G, et al.

Acute Lower Back Problems in Adults.

Clinical Practice Guideline No. 14.

Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research,

Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1994Yang H Haldeman S Lu ML Baker D

Low back pain prevalence and related workplace psychosocial

risk factors: a study using data from the 2010

National Health Interview Survey.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016; 39: 459-472Yang H Hitchcock E Haldeman S et al.

Workplace psychosocial and organizational factors for

neck pain in workers in the United States.

Am J Ind Med. 2016; 59: 549-560Lehman JJ Conwell TD Sherman PR

Should the chiropractic profession embrace

the doctrine of informed consent?

J Chiropr Med. 2008; 7: 107-114Spatz ES Krumholz HM Moulton BW

The new era of informed consent: getting to a reasonable-

patient standard through shared decision making.

JAMA. 2016; 315: 2063-2064Winterbottom M Boon H Mior S Facey M

Informed consent for chiropractic care:

comparing patients' perceptions to the legal perspective.

Man Ther. 2015; 20: 463-468Vining RD Minkalis AL Shannon ZK Twist EJ

Development of an Evidence-Based Practical Diagnostic

Checklist and Corresponding Clinical Exam for Low Back Pain

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 (Nov); 42 (9): 665–676Hill JC, Dunn KM, Lewis M, et al.

A Primary Care Back Pain Screening Tool:

Identifying Patient Subgroups For Initial Treatment

(The STarT Back Screening Tool)

Arthritis Rheum. 2008 (May 15); 59 (5): 632–641Kneeman J Battalio SL Korpak A et al.

Predicting persistent disabling low back pain in

Veterans Affairs primary care using the STarT Back tool.

PM R. 2021; 13: 241-249Stevans JM, Delitto A, Khoja SS, et al.

Risk Factors Associated With Transition From Acute to Chronic

Low Back Pain in US Patients Seeking Primary Care

JAMA Netw Open 2021 (Feb 1); 4 (2): e2037371Nicholas MK Linton SJ Watson PJ Main CJ

“Decade of the Flags” Working Group. Early identification and management

of psychological risk factors (“yellow flags”) in patients

with low back pain: a reappraisal.

Phys Ther. 2011; 91: 737-753Stearns ZR Carvalho ML Beneciuk JM Lentz TA

Screening for yellow flags in orthopaedic physical therapy:

a clinical framework.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021; 51: 459-469Carlson H Carlson N.

An overview of the management of persistent musculoskeletal pain.

Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2011; 3: 91-99Todd AJ, Carroll MT, Mitchell EK.

Forces of Commonly Used Chiropractic Techniques for Children:

A Review of the Literature

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016 (Jul); 39 (6): 401–410World Health Organization (WHO)

WHO Guidelines on Basic Training and Safety in Chiropractic

Geneva, Switzerland: (November 2005)Bezdjian S Whedon JM Russell R Goehl JM Kazal Jr., LA

Efficiency of Primary Spine Care as Compared to Conventional

Primary Care: A Retrospective Observational Study

at an Academic Medical Center

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2022 (Jan 6); 30 (1): 1LaPelusa A Bordoni B

High Velocity Low Amplitude Manipulation Techniques.

StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL 2021Pollock JD Skidmore HT

Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment: HVLA Procedure — Lumbar Vertebrae.

StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL 2021Whedon JM, Toler AWJ, Kazal LA, Bezdjian S, Goehl JM, Greenstein J.

Impact of Chiropractic Care on Use of Prescription

Opioids in Patients with Spinal Pain

Pain Medicine 2020 (Dec 25); 21 (12): 3567–3573

There are more like this at: SPINAL PAIN MANAGEMENTRondanelli M Faliva MA Miccono A et al.

Food pyramid for subjects with chronic pain: foods and dietary

constituents as anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agents.

Nutr Res Rev. 2018; 31: 131-151Machado GC Maher CG Ferreira PH et al.

Can recurrence after an acute episode of low back pain be predicted?

Phys Ther. 2017; 97: 889-895Bokhour BG Haun JN Hyde J Charns M Kligler B

Transforming the Veterans Affairs to a whole health system

of care: time for action and research.

Med Care. 2020; 58: 295-300Kazis LE, Ameli O, Rothendler J, et al.

Observational Retrospective Study of the Association

of Initial Healthcare Provider for New-onset Low Back

Pain with Early and Long-term Opioid Use

BMJ Open. 2019 (Sep 20); 9 (9): e028633Whedon JM, Toler AWJ, Goehl JM, Kazal LA.

Association Between Utilization of Chiropractic Services for

Treatment of Low-Back Pain and Use of Prescription Opioids

J Altern Complement Med. 2018 (Jun); 24 (6): 552–556Whedon JM Uptmor S Toler AWJ Bezdjian S MacKenzie TA Kazal Jr., LA

Association Between Chiropractic Care and Use of Prescription

Opioids Among Older Medicare Beneficiaries with Spinal Pain:

A Retrospective Observational Study

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2022 (Jan 31); 30: 5Fritz JM, Kim J, Dorius J.

Importance of the Type of Provider Seen to Begin Health Care

for a New Episode Low Back Pain: Associations with

Future Utilization and Costs

J Eval Clin Pract. 2016 (Apr); 22 (2): 247–252Keeney BJ, Fulton-Kehoe D, Turner JA, et al..

Early Predictors of Lumbar Spine Surgery After Occupational Back Injury:

Results From a Prospective Study of Workers in Washington State

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 (May 15); 38 (11): 953–964Khorsan R Coulter ID Hawk C Choate CG

Measures in chiropractic research:

choosing patient-based outcome assessments.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008; 31: 355-375Haas, M., Groupp, E., and Kraemer, D.F.

Dose-response for Chiropractic Care of Chronic Low Back Pain

Spine J 2004 (Sep); 4 (5): 574–583Pasquier M Daneau C Marchand AA Lardon A Descarreaux M

Spinal Manipulation Frequency and Dosage Effects on

Clinical and Physiological Outcomes: A Scoping Review

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2019 (May 22); 27: 23Knezevic NN Candido KD Vlaeyen JWS Van Zundert J Cohen SP

Low back pain.

Lancet. 2021; 398: 78-92Suri P Boyko EJ Smith NL et al.

Modifiable risk factors for chronic back pain:

insights using the co-twin control design.

Spine J. 2017; 17: 4-14Almeida M Saragiotto B Richards B Maher CG

Primary Care Management of Non-specific Low Back Pain:

Key Messages from Recent Clinical Guidelines

Medical J Australia 2018 (Apr 2); 208 (6): 272–275Tice JA Kumar V Otuonye I et al.

Cognitive and Mind-body Therapies for Chronic Low Back and

Neck Pain: Effectiveness and Value.

Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, Boston, MA 2017Farabaugh RJ, Dehen MD, Hawk C.

Management of Chronic Spine-Related Conditions:

Consensus Recommendations of a Multidisciplinary Panel

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010 (Sep); 33 (7): 484–492Kongsted A, Ris I, Kjaer P, et al.

Self-management at the Core of Back Pain Care:

10 Key Points for Clinicians

Braz J Phys Ther 2021 (Jul); 25 (4): 396–406Oliveira CB Maher CG Pinto RZ et al.

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific

low back pain in primary care: an updated overview.

Eur Spine J. 2018; 27: 2791-2803Traeger A Buchbinder R Harris I Maher C

Diagnosis and management of low-back pain in primary care.

CMAJ. 2017; 189: E1386-E1395Traeger AC Lee H Hübscher M et al.

Effect of intensive patient education vs placebo patient education

on outcomes in patients with acute low back pain: a randomized clinical trial.

JAMA Neurol. 2019; 76: 161-169Piano L Ritorto V Vigna I Trucco M Lee H Chiarotto A

Individual patient education for managing acute and/or subacute

low back pain: little additional benefit for pain and function

compared to placebo. a systematic review with meta-analysis

of randomized controlled trials.

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2022; 52: 432-445Furlong B Etchegary H Aubrey-Bassler K Swab M Pike A Hall A

Patient education materials for non-specific low back pain

and sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

PLoS One. 2022; 17e0274527Smuck M Barrette K Martinez-Ith A Sultana G Zheng P

What does the patient with back pain want? A comparison

of patient preferences and physician assumptions.

Spine J. 2022; 22: 207-213Sen I D'Oria M Weiss S et al.

Incidence and natural history of isolated abdominal aortic dissection:

a population-based assessment from 1995 to 2015.

J Vasc Surg. 2021; 73: 1198-1204Galliker G Scherer DE Trippolini MA Rasmussen-Barr E LoMartire R Wertli MM

Low back pain in the emergency department: prevalence of serious

spinal pathologies and diagnostic accuracy of red flags.

Am J Med. 2020; 133: 60-72

Return to LOW BACK PAIN

Return to BEST PRACTICES

Return to LOW BACK GUIDELINES

Since 6-21-2023

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |