Patient Safety Culture Research Within

The Chiropractic Profession: A Scoping ReviewThis section is compiled by Frank M. Painter, D.C.

Send all comments or additions to: Frankp@chiro.org

FROM: Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2025 (Oct 21); 33: 46 ~ FULL TEXT

OPEN ACCESS Debbie S Wright • Maranda Kleppe • Brian C Coleman • Martha Funabashi

Amy G Ferguson • Richard Brown • Sidney M Rubinstein

Stacie A Salsbury • Katherine A Pohlman

Parker University,

2540 Walnut Hill Ln,

Dallas, TX, 75229, USA.

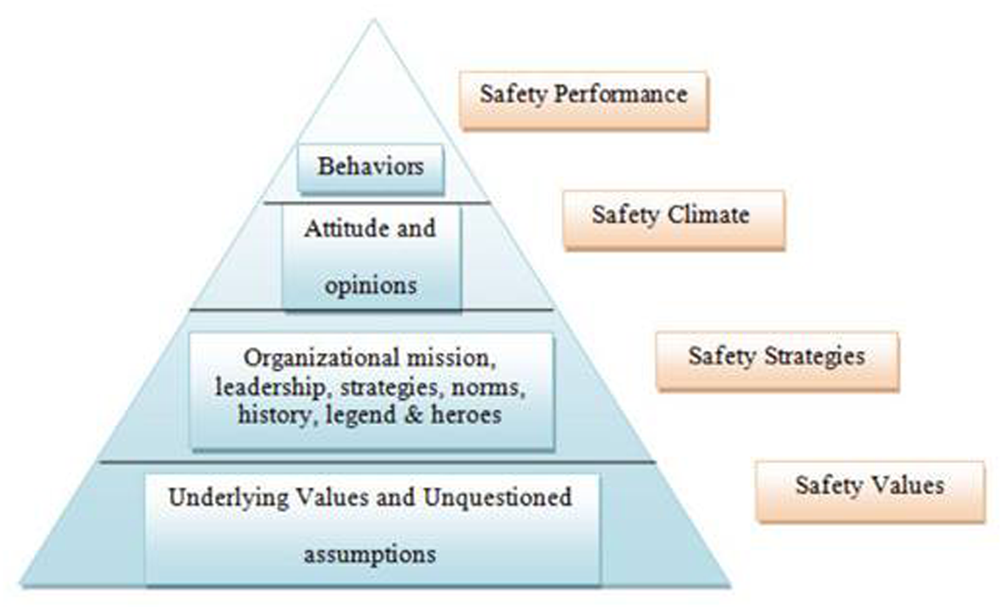

The Patient Safety Culture Pyramid

Introduction: A proactive patient safety culture is crucial in healthcare to minimize preventable harm and improve patient outcomes. This scoping review explores key themes, trends, and gaps in patient safety culture research within the chiropractic profession.

Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted across 5 databases from inception to December 2024. Peer-reviewed, English-language studies focusing on chiropractic patient safety culture were included. Following scoping review methodology, articles were screened, data were extracted, and both qualitative and quantitative analyses were conducted. External consultants from patient safety-focused chiropractic groups were sought to review findings. Trends and themes were identified, and findings were compared against established patient safety frameworks to highlight research gaps and future directions.

Results: Of the 3,039 screened articles, 65 met the inclusion criteria, spanning from 1990 to 2024, with 2 identified as randomized trials. Eight major themes were organized:(1) adverse event research,

(2) clinical trial safety reporting,

(3) patient safety attitudes,

(4) clinical decision making,

(5) informed consent,

(6) reporting and learning systems,

(7) office sanitization, and

(8) general safety topics.Mapping these studies onto the Patient Safety Culture Pyramid framework revealed that 95% addressed safety performance, 81% covered safety processes, and only 23% explored beliefs and values. Comparisons with the WHO Global Patient Safety Action Plan framework highlighted advancements in clinical process safety while revealing research gaps in patient engagement, policy development, leadership, and interprofessional collaboration. Key recommendations include standardizing adverse event reporting, improving communication strategies, and developing structured approaches to patient and provider safety. External consultation provided minimal feedback requiring modifications.

Conclusion: This review underscores significant advancements and gaps in chiropractic patient safety culture research, particularly in leadership, policy, and interprofessional engagement. Future research should focus on implementing and evaluating evidence-based safety interventions to enhance transparency, improve patient outcomes, and build public trust in chiropractic care. Direct stakeholder engagement, including with patients, is necessary to determine the most effective strategies for integrating patient safety within the global chiropractic profession.

Keywords: Adverse event; Chiropractic; Patient harm; Patient safety; Risk management; Safety management; Spinal manipulation.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Patient safety is central to all domains of healthcare. [1, 2] While adverse events and healthcare errors are dominant topics and often the focus of safety initiatives [2], the World Health Organization (WHO) defines patient safety more broadly as “the absence of preventable harm to a patient and reduction of risk of unnecessary harm associated with health care to an acceptable minimum”. [3] This broader perspective incorporates structured activities and intangible aspects, such as cultivating specific cultures, systems, and behaviors, to enhance safety in healthcare delivery. These activities and aspects together embody the concept of “patient safety culture”.

The Institute of Medicine report, To Err is Human, describes patient safety culture as “a healthcare organization’s values, commitment, competencies, and actions in pursuit of patient safety”. [2] This definition further highlights that shared values and beliefs (i.e. culture), when aligned with an organization’s structures and systems, foster behavioral practices that enhance patient safety. [4] Systematic, coordinated, and consistent approaches to patient safety reduce risks, as well as the frequency and impact of avoidable harm. [1, 3] Therefore, efforts to understand and improve patient safety culture may yield more sustainable benefits than focusing solely on the harms themselves.

Chiropractic care is used widely for managing musculoskeletal conditions [5], and presents unique challenges to patient safety due to the diversity of practitioner approaches and practice settings, ranging from independent ambulatory clinics to those integrated within medical multispecialty groups (including hospitals). These variabilities in practitioner approaches and practice settings can impact patient safety in chiropractic care, with available knowledge limited to sparse data collected from surveys and surveillance systems. [6–8] A comprehensive systematic examination of patient safety culture initiatives within chiropractic is timely to establish an effective safety strategy, agree on a unified framework, and map a future research agenda.

This scoping review synthesizes the extent, range, and themes of patient safety culture research activities in the chiropractic profession. Additionally, our findings are mapped against the Patient Safety Culture Pyramid [9] and the WHO Global Patient Safety Action Plan [1], two robust and relevant patient safety frameworks, to identify areas of alignment and gaps in patient safety culture interventions or strategies. These efforts will establish a foundation of the current evidence in response to a recent “Call to Action” issued by the World Federation of Chiropractic (WFC) Global Patient Safety Task Force (now known and subsequently referred to as the WFC Global Patient Safety initiative), advocating for the advancement of patient safety in chiropractic. [10]

We aim to inform the development of a tailored guide for future chiropractic-specific patient safety research, emphasizing the evaluation of patient safety attitudes, beliefs, performance measurements, and strategic interventions to foster a robust patient safety culture within the profession. To this aim, this scoping review will explore key themes, trends, and gaps in patient safety culture research within the chiropractic profession.

Methodology

Design

The scoping review methodology was selected to explore and map the breadth of evidence related to patient safety culture research in chiropractic. This study adheres to the well-established, multi-staged process outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [11] and further refined by Levac et al. [12] for scoping reviews. For reporting, the study followed the Preferred Reporting Items Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-SCR) guidelines [13] (see Additional File 3 for checklist).

The protocol was registered prospectively with the Open Science Framework (OSF) Registry [14] and updated to include more specific inclusion and exclusion criteria listed in Stage 3 below. A protocol refinement was implemented to exclude best practice documents, clinical practice guidelines, and single-case studies from the study selection process. Given their nature, these sources do not constitute primary research and therefore do not align with the definition of patient safety culture research within the chiropractic profession, as outlined in Stage 1 below.

This scoping review followed this multi-stage process:(1) research objective identification,

(2) relevant study identification,

(3) study selection,

(4) data charting,

(5) data synthesis and reporting, and

(6) consultation.Stage 1: Research objective identification

This scoping review aimed to explore and map the extent, range, and themes of patient safety culture research conducted within the chiropractic profession. We defined “patient safety culture” as attitudes, beliefs, practices, performance, or policy/procedure pertaining to the safe delivery of, or experience with, healthcare or the healthcare system, adapting the WHO definition [3] to reflect the chiropractic setting. Relevance to the chiropractic profession was defined as research addressing patient safety within chiropractic care, including — but not limited to — the unique risks and considerations associated with spinal manipulation therapy. [15] This focus highlights the critical need to identify, understand, and mitigate potential safety concerns inherent in hands-on therapeutic interventions, a cornerstone of chiropractic practice.

Stage 2: Relevant study identification

Information sources. A medical librarian and scoping review strategist (AF) conducted a comprehensive literature search. The following electronic databases were searched from inception until March 15, 2024, with an updated search performed on December 16, 2024:(1) MEDLINE (OVID) [16],

(2) Index to Chiropractic Literature [17],

(3) Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (EBSCO) [18],

(4) Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (EBSCO) [19], and

(5) Google Scholar. [20]Search strategy. This strategy was developed collaboratively by study investigators with domain expertise (SR, KAP, DSW) and a medical librarian (AF). Before implementation, the strategy was peer-reviewed using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) framework. [21] National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and relevant keywords were used to search titles and abstracts for concepts such as chiropractic, patient safety, adverse events, and safety culture. [22] Backward citation searching, which involved reviewing the references cited by known relevant articles to identify additional pertinent studies, was used to identify further eligible articles. [23] A complete search strategy for each database can be found in Additional File 1.

Stage 3: Study selection

Eligibility Criteria. Eligible studies reported on patient safety culture research conducted within, related to, or including the chiropractic profession. Studies were included if they were written in English and consisted of quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, or quality improvement studies, review articles, and brief reports reporting original investigations on patient safety culture. Exclusion criteria were non-original research articles (e.g., conference abstracts), opinion articles (e.g., editorials, letters to the editor, commentaries), case reports of a single individual, articles with inaccessible full-text versions, general best practice documents or clinical practice guidelines related to chiropractic care, non-peer-reviewed publications, and studies reporting solely on adverse event data derived from clinical studies without a specific focus on patient safety culture.

Search results were de-duplicated and imported into Covidence [24], a web-based application for citation management for systematic and scoping reviews. Two independent reviewers (KAP, DSW) screened titles and abstracts based on the a priori eligibility criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussion, with input from a third reviewer (SAS) when necessary. Full-text articles deemed potentially eligible were independently screened by two reviewers (DSW, MK) using the same criteria, with any conflicts resolved by consensus discussion.

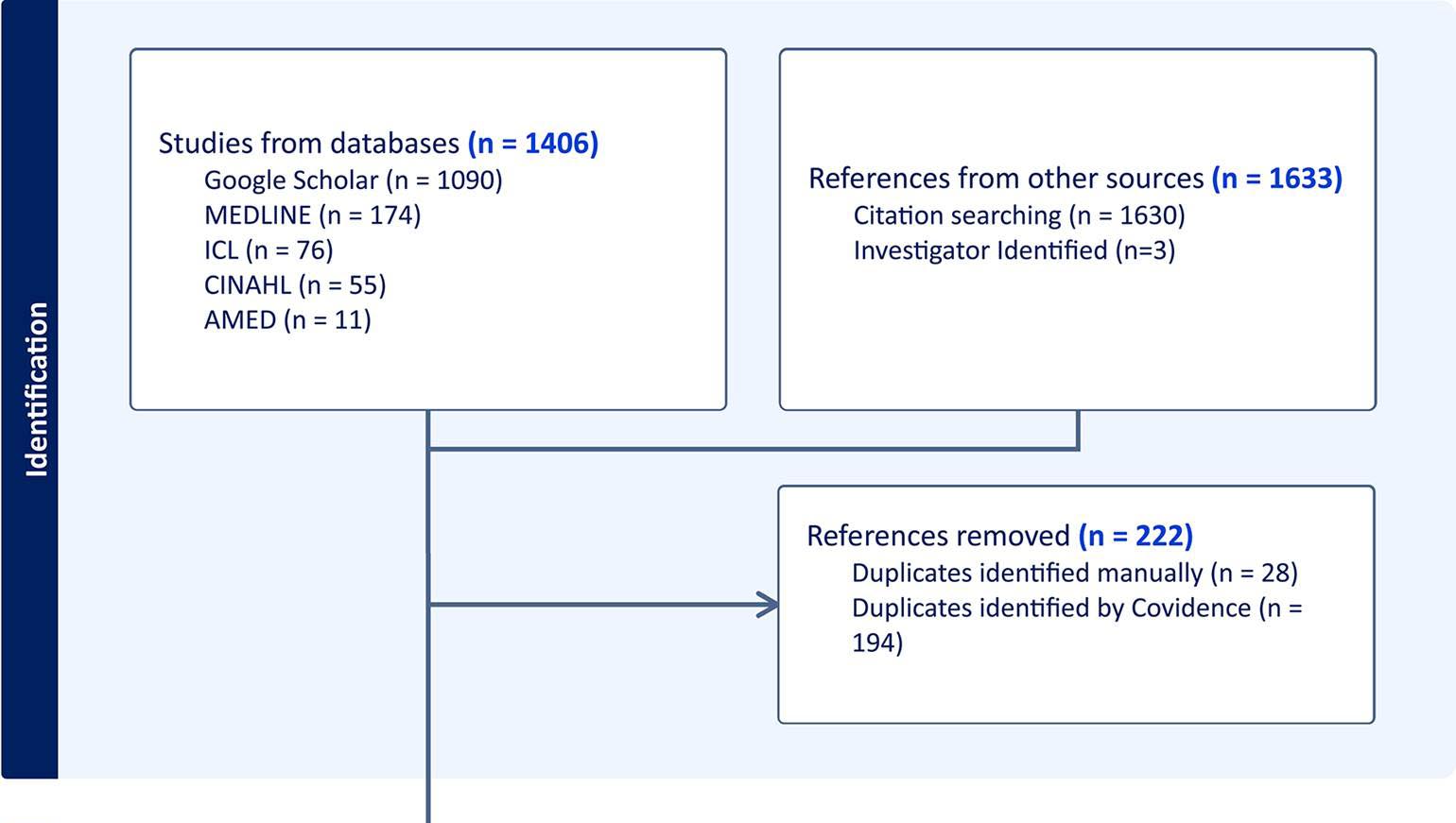

Figure 1

page 4Backwards citation searching of included articles was used to identify additional unique studies. These were imported into Covidence and screened through the same title/abstract and full-text review process. Articles that met the inclusion criteria following full-text screening were used for data extraction. The flow of studies through the review process is detailed in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Stage 4: Data charting

Two reviewers (DSW, MK) extracted data from the included studies using a standardized data extraction form, created a priori, pilot-tested with 5 studies, and subsequently refined. All data were extracted in batches independently by one reviewer (DSW, MK) and verified by the other, with each reviewer completing approximately half of the full extractions. Small group discussions and consensus (DSW, MK, KAP, SAS) determined the final dataset.

Extracted data included the following: study metadata and characteristics (e.g., author(s), year of publication, article title, aims and objectives, country of origin), population, methodology, intervention(s) and comparator(s) (if applicable), outcome measure(s) (if applicable), patient safety culture finding implications (most often found in the results or discussion sections), and study limitations. Additional recorded data included results related to patient safety approaches, patient safety considerations, and other noteworthy findings. Safety approaches encompassed findings on patient safety attitudes, opinions, and beliefs, while safety considerations included specific actions, tools, or systems designed to enhance patient safety culture within chiropractic practice.

In alignment with the WHO Global Patient Safety Action Plan [1], three reviewers (DSW, MK, KAP) independently identified data pertaining to strategic objectives. This process focused on documenting action items related to patient safety culture and identifying suggestions for future research.

Stage 5: Data synthesis and reporting

Data synthesis involved a qualitative analysis of the features of patient safety culture, such as attitudes and performance, extracted from the included studies. From these features, a thematic analysis was conducted by the study team (DSW, MK, KAP, SAS) to identify clusters of studies centered around similar domains within patient safety culture. Studies and themes were then mapped to two relevant patient safety frameworks: the Patient Safety Culture Pyramid [9] and the WHO Global Patient Safety Action Plan. [1]

The Patient Safety Culture Pyramid illustrates the dynamic nature of safety culture, starting with core values and underlying assumptions at its base. These foundational elements support organizational components such as strategies, leadership, and policies. Above these, the safety climate is shaped by the attitudes, opinions, and processes of organizational members, ultimately culminating in safety performance at the peak, which is defined by behaviors and outcomes. [9] A quantitative analysis determined the percentage of studies addressing each pyramid level. Studies evaluating clinician or patient behaviors and outcomes, and adverse events themselves were classified as addressing Performance. Studies evaluating the values and beliefs underpinning patient safety culture were classified as addressing Values. To enhance clarity and practical applicability, we merged the middle two levels of the Patient Safety Culture Pyramid — climate and strategies — into a single category, Processes.

The Global Patient Safety Action Plan, developed by the WHO, comprises seven strategic objectives designed to guide stakeholders in improving patient safety and reducing preventable harm in healthcare globally. A quantitative and qualitative analysis was conducted, with each included study mapped to the seven strategic objectives and analyzed to determine whether it addressed them directly or indirectly. A study was classified as “direct” if it explicitly focused on one of the Global Patient Safety Action Plan’s objectives and investigated its principles as a primary focus. Alternatively, studies were categorized as “indirect” if they provided information relevant to a Global Patient Safety Action Plan objective but did so incidentally or as part of a broader discussion. While indirect studies did not directly address specific objectives, they provided valuable insights into understanding and implementing the Global Patient Safety Action Plan framework.

Stage 6: Consultation

Our findings were presented to three key chiropractic organizations with expertise in patient safety. First, the WFC Research Committee (n = 15) was consulted for feedback. As an official non-state actor of the WHO, the WFC represents the global chiropractic profession. [25] Second, input was sought from attendees of the Chiropractic Association of Alberta (CAA) Patient Safety Round Table (n = 26). The CAA is a member-based organization dedicated to advancing chiropractic care in Alberta, Canada. [26] Finally, the Royal College of Chiropractors (RCC) (n = 4) was engaged to provide practical insights. The RCC is a professional membership body, based in the United Kingdom, that upholds high standards of quality, safety, and professionalism in chiropractic practice, education, and research. [27] RCC also oversees the Chiropractic Patient Incident Reporting and Learning System (CPiRLS), a database enabling collaborating chiropractors to report, review, and discuss patient safety incidents. Stakeholder input focused on the study’s comprehensiveness — ensuring all relevant literature was included — the validity of the identified themes, and the appropriateness of the analytical frameworks. Additionally, feedback was requested on the clinical implications of the findings and recommendations for future research. All documentation related to the consultation process can be found in Additional File 4.

Results

Search results

Our search identified 3039 publications, with 222 duplicates removed (Figure 1). An initial abstract and title screening of the remaining 2817 records yielded 268 articles for full-text review, excluding 2549 records for the following reasons: not being chiropractic-related, lacking a focus on patient safety culture, or not constituting original research. One full-text article could not be retrieved and was excluded. Following the full-text screening of the remaining 267 articles, 65 were included as relevant to the research question and meeting the inclusion criteria, with 202 publications excluded. A list of full-text excluded references and the reasons for their exclusion is provided in Additional File 2.

Table 1

page 6Table 1 describes the 65 publications included in this review. [6–8, 15, 28–88] The publication dates ranged from 1990 to 2024, with 3 articles published before 2000 [28–30], 16 between 2000 and 2009 [31–46], 32 between 2010 and 2019 [6, 35–65], and 14 published in 2020 or later. [7, 8, 77–88]

Among these, 16 articles described studies completed in Canada

[6, 40, 47, 52, 53, 56, 59, 61, 67, 71–73, 75, 77, 80, 86],

15 in the United States

[7, 28, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 41, 45, 50, 51, 55, 65, 76, 85],

10 in the United Kingdom

[8, 15, 31, 34, 42, 43, 46, 48, 49, 58],

4 in Australia

[29, 30, 57, 66],

2 in Italy

[63, 64],

1 in Norway

[60],

and 17 were comprised of international research teams.

[37, 39, 44, 54, 62, 68–70, 74, 77–83, 87, 88]

The publications included various study designs:cross-sectional studies (n = 17)

[6, 8, 31–33, 37, 49, 51, 58, 70, 71, 73, 74, 76, 77, 79, 81],

qualitative descriptive research (n = 13)

[29, 30, 35, 42, 52, 54–56, 63, 67, 72, 75, 82],

observational studies (n = 11)

[7, 28, 34, 36, 39, 41, 43, 44, 60, 86, 87],

systematic/scoping reviews (n = 10)

[15, 40, 47, 62, 65, 68, 69, 83, 84, 88],

narrative reviews (n = 6)

[45, 46, 53, 63, 66, 85],

case series (n = 4)

[38, 50, 59, 80],

randomized clinical trials (RCTs) (n = 2)

[57, 78],

an instrument development study (n = 1)

[61],

and a Delphi consensus panel (n = 1).

[48]

Thematic analysis

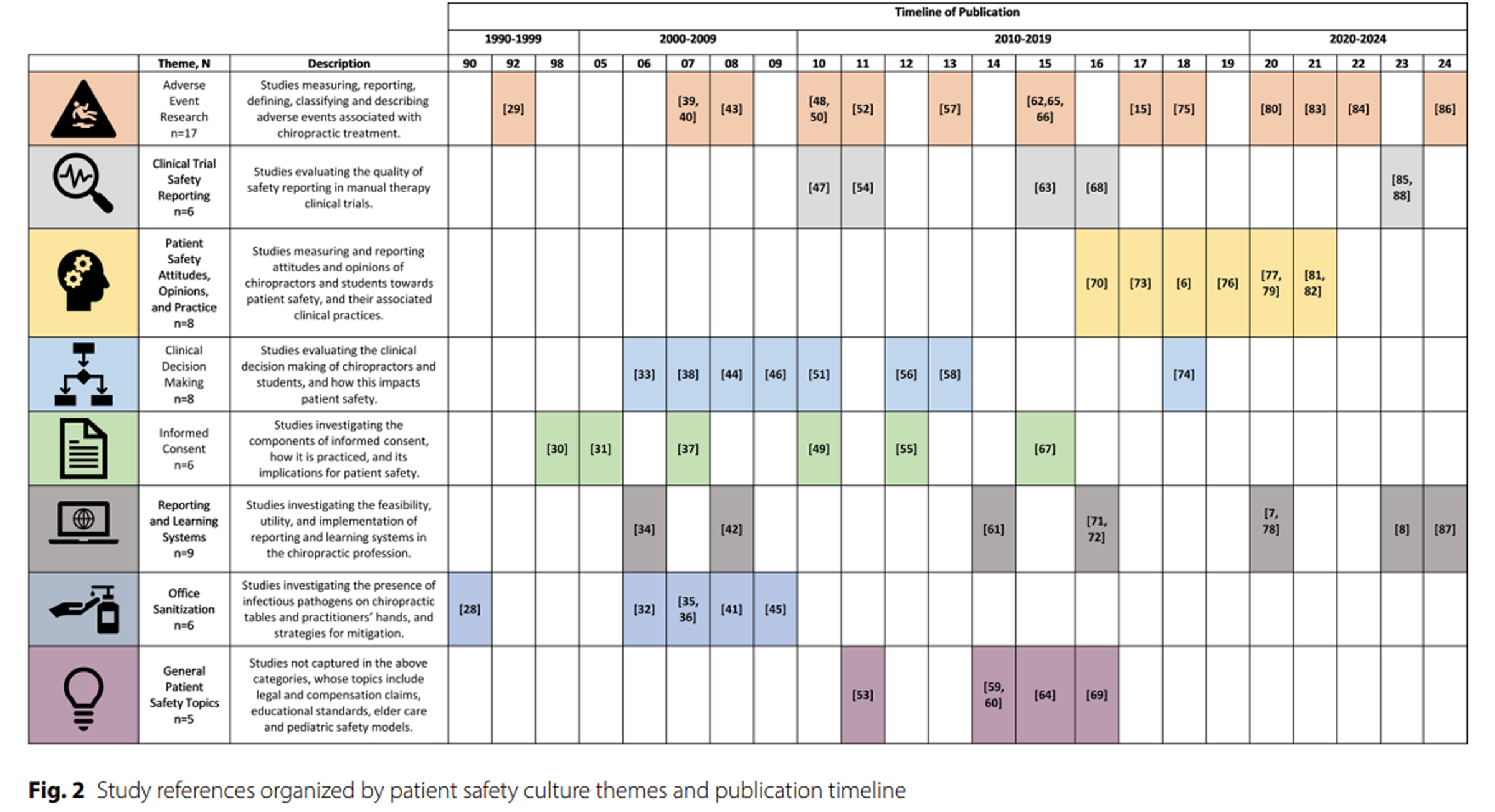

Figure 2 Figure 2 presents the thematic results by the number of studies and years of publication, in which 8 patient safety culture themes were generated: Adverse Event Research (n = 17), Clinical Trial Safety Reporting (n = 6), Patient Safety Attitudes, Opinions, and Practice (n = 8), Clinical Decision Making (n = 8), Informed Consent (n = 6), Reporting and Learning Systems (n = 9), Office Sanitization (n = 6), and General Patient Safety Topics (n = 5). Below is a summary of the key findings for each theme.

Theme 1: Adverse event research (n = 17)

Seventeen studies (1992–2024) examined the measurement, reporting, classification, and description of adverse events following chiropractic treatment. [15, 29, 39, 40, 43, 48, 50, 52, 57, 62, 65, 66, 75, 80, 83, 84, 86] While serious adverse events were rare, benign and transient adverse events were common, often attributable to nonspecific effects. [15, 39, 57, 83] The included studies highlight ongoing challenges in standardizing adverse event terminology and classification. [48, 52, 84] Recent research has built upon earlier findings, exploring outcomes in diverse settings, including pediatric and teaching clinics. [80, 86]

Theme 2: Clinical trial safety reporting (n = 6)

Six studies (2010–2023) evaluated adverse event and safety reporting in manual therapy clinical trials [47, 54, 63, 68, 85, 89] revealing inconsistencies and inadequacies, a challenge not unique to the chiropractic field. [88, 89] Findings reinforced the need for standardized adverse event reporting in both clinical and research settings. [63, 85] While the 2010 Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guideline included a basic reporting statement [47, 54, 68], a 2022 extension introduced a more structured approach. [89] The rise in publications after 2010 could indicate an initial attempt to evaluate whether the research community began following these guidelines. [80]

Theme 3: Patient safety attitudes, opinions, and practice (n = 8)

Eight studies (2016–2021) explored chiropractors’ and students’ perspectives on patient safety and their clinical practices [6, 70, 73, 76, 77, 79, 81, 82], many led by the interprofessional, international SafetyNET team. [6, 7, 61, 70, 71, 78, 79, 82, 87, 91] Findings highlight the importance of strengthening patient safety culture by addressing training gaps. [6, 73, 79, 82] Recent trends emphasize evaluating safety dimensions — performance, processes, and values [92] — rather than solely documenting harm incidence.

Theme 4: Clinical decision making (n = 8)

Eight studies (2006–2018) investigated chiropractic clinical decision making with an emphasis on patient safety. [33, 38, 44, 46, 51, 56, 58, 74] Findings suggest that refined clinical assessment skills — such as appropriate referral, triage, and re-evaluation — enhance safety. [33, 38, 58] Most studies were published between 2006 and 2013, with limited exploration in the past decade.

Theme 5: Informed consent (n = 6)

Six studies (1998–2015) analyzed the components of informed consent, its practice, and implications for patient safety. [30, 31, 37, 49, 55, 67] Research, particularly active between 2007 and 2015, revealed inconsistencies and non-compliance in informed consent processes [30, 31, 49]; however, research in this area has not been updated in recent years.

Theme 6: Reporting and learning systems (n = 9)

Nine studies (2006–2024) explored chiropractic reporting and learning systems [7, 8, 34, 42, 61, 71, 72, 78, 87], highlighting low awareness and uptake of CPiRLS. [8, 42] While CPiRLS has expanded in Europe, use of comparable systems is lacking in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Similarly, assessment of chiropractic care related safety data is absent from healthcare systems offering chiropractic services with more general patient safety incident reporting and learning systems. Active surveillance is more effective than passive surveillance in adverse event detection, though passive surveillance remains valuable for broad coverage, cost-effectiveness, and early signal detection. [7–9, 71, 78, 87] Research in this area has grown since 2008.

Theme 7: Office sanitization (n = 6)

Six studies (1990–2009) examined microbial contamination on chiropractic tables and practitioners’ hands, highlighting the need for systematic disinfection protocols. [28, 32, 35, 36, 41, 45] Despite its relevance, office sanitization research was absent in recent years, including during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Theme 8: General patient safety topics (n = 5)

Five studies (2011–2016) emphasized the need for age-specific treatment modifications [53, 64], improved communication and differential diagnosis to better mitigate legal claims [59, 60], and the need for educational competencies to enhance patient safety. [69]

Framework mapping

Figure 3

page 37

Figure 4

page 38Figures 3 and 4 illustrate key trends in chiropractic patient safety research mapped to relevant patient safety frameworks. Figure 3 maps studies onto the Patient Safety Culture Pyramid, showing that most research addressed multiple safety culture levels: 95% examined performance, 81% addressed processes, and only 23% explored core safety values — a critical gap because values shape attitudes, behaviors, and decision-making. [9] To strengthen safety culture, recommendations include integrating safety climate surveys into research initiatives and establishing a patient safety culture database for spinal manipulation therapy providers, enabling long term quality improvement. [6, 77, 81]

Figure 4 compares the included studies with the WHO Global Patient Safety Action Plan [1] while highlighting research gaps. While many studies (n = 46) focused on clinical safety processes, far fewer examined policy (n = 3), high reliability systems (n = 9), or interprofessional collaboration (n = 13). Few studies directly addressed patient safety policies, though some indirectly recommended improvements in sanitization, informed consent, and competency standards. [31, 45, 69] Strengthening policy efforts is essential to advance chiropractic patient safety culture and align with the WHO goal of zero avoidable harm in healthcare.

Research on high reliability systems emphasized leadership in safety culture [7, 34] and intra-organizational collaboration in safety reporting [82], but key areas – human factors, ergonomics, and governance – remain unaddressed. Similarly, studies on synergy and partnerships highlighted interprofessional collaboration [33, 51, 72, 82, 84] and education [40, 73, 76] but lacked focus on developing global patient safety networks. Patient engagement also was underrepresented. Only one-third of the studies engaging patients involved direct patient input, with most discussing engagement conceptually. Patient perspectives were examined in adverse event definitions [52], adverse event mitigation [77], and informed consent. [67] Future research should prioritize direct patient involvement to strengthen patient safety culture across all levels. [70, 80]

Consultation

Finally, for Stage 6 – Consultation, the research team received feedback from key partner representatives regarding the comprehensiveness of the scoping review (see Additional File 4 for all results). Suggestions were primarily related to semantic changes for clarity, and included adding a specific example of the current inconsistency in adverse event definitions. Additional comments highlighted important perspectives on topics related to patient safety (e.g., safety risk in special populations, health system complexities, safety measurement criteria) but were outside of the primary focus of this review on patient safety culture.

Discussion

This scoping review identified 65 articles that collectively outline the breadth of patient safety culture research in chiropractic while revealing critical gaps in policy development, high reliability systems, interprofessional collaboration, and direct patient engagement. Most of the research centered on performance (95%) and processes (81%), with core safety values (23%) remaining underexplored. Strengthening safety climate assessments, regulatory policies, and patient engagement strategies is necessary to foster a more robust and evidence-based patient safety culture in chiropractic.

The findings indicate that the chiropractic profession's patient safety culture is evolving, with the identified themes highlighting both advancements and ongoing challenges. The frequency of benign adverse events associated with chiropractic treatment underscores the need for standardized reporting and terminology. [48, 52, 84] Despite efforts to enhance harm reporting through guidelines like the CONSORT, inconsistencies persist in clinical trials. [88] Informed consent remains another critical yet underexplored aspect of patient safety, with past research revealing significant variability and non-compliance in its implementation across different settings. [55, 67] The decline in recent studies on informed consent, particularly as new methods of delivering, discussing, and documenting consent are being developed, suggests a gap in understanding how to ensure patients receive clear, consistent, and comprehensive information about potential risks and benefits of chiropractic care.

Emerging research increasingly emphasizes patient safety culture dimensions — performance, processes, and values — shifting the focus from documenting harms to driving proactive improvements. [6, 91] Despite this progress, research on patient safety education and training remains limited within the chiropractic profession. Strengthening interprofessional collaboration, enhancing safety-focused curricula at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels, and fostering a culture of shared responsibility were identified as essential next steps in advancing patient safety within the chiropractic profession.

To align chiropractic patient safety research with global health priorities, future studies should expand beyond adverse event reporting and address patient-centered safety culture, as outlined in the WHO Global Patient Safety Action Plan [1], and the WFC Global Patient Safety Initiative’s “Call to Action”. [10] Several key areas require further investigation.

Regulatory frameworks and policy development

There is a need for regulatory policies and competency standards addressing standardized informed consent, surveillance systems for adverse events, and patient safety training. Policymakers should prioritize developing and adopting structured reporting and learning systems that support high reliability systems and cross-disciplinary collaboration, as recommended by the WHO Global Patient Safety Action Plan. [7, 8, 34, 42, 55, 61, 67, 87]

Standardizing adverse event reporting and safety data collection

The absence of standardized adverse event definitions and classification systems remains a major obstacle to effective reporting and meta-analysis in chiropractic research. [42, 49, 52, 63, 68, 84, 85, 88] While adverse events dominate patient safety discussions in professional discourses and social media posts alike, future efforts should prioritize establishing consistent terminology and reporting structures to enhance data accuracy and comparability. In addition to the widespread inconsistency in terminology used to report adverse events, further complications arise from variability in the populations studied — a large proportion of research focuses on pediatric patients [40, 43, 63, 70, 71], while significantly less attention given to older populations [53, 76], limiting the generalizability of findings across age groups. Additionally, foregrounding patient perspectives in adverse event definitions, reporting structures, and mitigation strategies will ensure a more patient-centered approach. Expanding and systematically integrating safety values assessments into chiropractic research and practice is essential for fostering a stronger patient safety culture. [4, 6, 9]

Enhancing patient engagement in safety research

Although patient engagement is a critical component of WHO Global Patient Safety Action Plan [1], few chiropractic studies have directly involved patients in safety discussions or decision-making processes. Patient engagement refers to the meaningful involvement of patients and their families as equal partners in all aspects of health care — ranging from bedside decisions to national policy — by ensuring their voices, experiences, and rights are integrated into governance, strategy, safety reporting, and care delivery, with full transparency, access to information, and opportunities to influence and co-lead improvements in patient safety. [1] Engaging patients in safety initiatives enhances transparency, improves communication, and reduces preventable harm. [93, 94] Future research should actively include patients in defining safety priorities, reporting experiences, and shaping care improvements. [52, 67, 70, 77]

Building high reliability systems and interprofessional collaboration

Chiropractic lacks well-established and broadly adopted high reliability systems — critical for minimizing errors and ensuring continuous learning from safety incidents. [95] Future research should explore how safety culture is influenced by practitioner approaches and practice settings, in addition to governance structures, leadership involvement, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Integrating patient safety research across professions could yield synergistic solutions, benefiting both chiropractic and the broader healthcare community. [96, 97] This presents an opportunity for future research to analyze patient safety data from healthcare systems that have integrated chiropractic care, such as the United States Veterans Health Administration. [98, 99] Comparing this data with other health professions can provide valuable insights. Additionally, studies to examine the impact of system dynamics and operational workflows in chiropractic clinics within high reliability organizations on patient safety outcomes can offer a model for chiropractic practice across diverse healthcare settings. [100]

While chiropractors play a critical role in patient safety, there is a disconnect between clinical practice, education, and research in addressing system-wide safety concerns. Research must move beyond documenting individual safety events and include the development and evaluation of interventions that enhance safety culture. This could include the advancement of the use of CPiRLS, or similar reporting systems on a global scale. The CPiRLS system is a voluntary, anonymous reporting tool for documenting adverse events, near misses, and safety concerns in chiropractic care, aimed at promoting a culture of learning. However, its effectiveness is limited by challenges such as underreporting and low engagement, highlighting the need for improved reporting methods and greater education on patient safety. [8, 42]

Expanding active surveillance initiatives will improve adverse event detection, risk mitigation, and safety policy development. Active surveillance initiatives use structured methods — such as follow-up interviews, electronic monitoring, and direct data collection — to more accurately identify and report adverse events in healthcare. These systems generate standardized, reliable data and detect significantly more AEs than passive reporting. [78] However, they are resource-intensive, requiring greater time, cost, and clinician involvement, and face similar barriers to engagement as passive systems, including time constraints and fear of blame. [7, 78] While underutilized, especially in ambulatory care, active surveillance is recognized as a valuable tool for improving patient safety.

Chiropractic education programs should also integrate competency-based patient safety training, ensuring that future practitioners are equipped with the skills to proactively prevent and manage safety risks and incidents. Lastly, research on synergy and partnerships is underdeveloped, despite the WHO emphasis on collaborative patient safety efforts. Future research should explore how chiropractic can contribute to global patient safety networks and participate in interdisciplinary safety initiatives. Additionally, meta-analyses and longitudinal studies evaluating the effectiveness of patient safety interventions on chiropractic are essential to drive evidence-based improvements.

Near misses

Many studies excluded during the screening process were “near misses” – relevant to patient safety but lacking explicit discussion of patient safety culture. Research on regulatory complaints [101, 102], culturally sensitive care [103], and interprofessional referral patterns [104] provided valuable insights, but did not specifically analyze or discuss study results through a patient safety culture lens. Additionally, chiropractic best practices and clinical guidelines (see Additional File 2 for the 14 identified best practice and clinical practice guidelines excluded in this review), often overlook patient safety implications, warranting future investigation. Future research should systematically analyze case reports, clinical guidelines, and best practice recommendations to assess their impact on patient safety.

Strengths and limitations

This review followed a rigorous, stepwise methodology, ensuring comprehensive data extraction and analysis [11, 12], with the protocol pre-registered on OSF. An international, interprofessional research team contributed expertise in scoping reviews and patient safety, while a medical librarian oversaw the search strategy, including a PRESS peer-review [21], enhancing study reliability. We did not include EMBASE in our search, nor grey literature, meaning potentially relevant studies may have been omitted; however, we used backward citation searching as an additional step in order to minimize missing studies. Additionally, some studies presented ambiguous patient safety information, offering indirect rather than explicit findings on safety culture, which may have affected the assessment of relevance and strength. Lastly, the inclusion of only English-language publications limits generalizability, potentially overlooking important studies from non-English speaking regions. This said, only 2 studies were excluded for non-English language of publication, suggesting that patient safety culture research may be limited outside the geographic regions identified in our analysis.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights the breadth of patient safety culture research in chiropractic while identifying key gaps in adverse event reporting, informed consent, and incident reporting systems. Despite progress in adverse event research and clinical safety, challenges remain, including inconsistent reporting, lack of standardized terminology, and limited patient engagement. To align with global safety standards, future research should focus on regulatory frameworks, standardized adverse event reporting, patient engagement, and high reliability systems. Strengthening safety values in chiropractic practice and education is essential for fostering a sustainable patient safety culture. By maintaining a focus on continuous advancements in chiropractic safety research, the profession can enhance transparency, accountability, and alignment with WHO Global Patient Safety Action Plan priorities while ensuring safer and more effective chiropractic care.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material 1

Search Strategies for all Databases

Supplementary Material 2

Reasons for Article Exclusion During Full Text Screening

Supplementary Material 3

Consultation Process

Supplementary Material 4

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) ChecklistAbbreviations

WHO: = World Health Organization

WFC: = World Federation of Chiropractic

PRISMA-SCR: = Preferred Reporting Items Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews

OSF: = Open Science Framework

PRESS: = Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies

MeSH: = Medical Subject Headings

CAA: = Chiropractic Association of Alberta

RCC: = Royal College of Chiropractors

CPiRLS: = Chiropractic Patient Incident Reporting and Learning System

RCT: = Randomized Clinical Trial

CONSORT: = Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the stakeholders who agreed to participate in our consultation process, thereby ensuring the rigor and quality of this study. We specifically acknowledge the following participants for their assistance with this consultation process: Dr. Peter Shipka, Dr. Jennifer Adams-Hessel, and Dr. Gabrielle Swait. The authors would like to acknowledge Carrie Owens, MSILS of Research Support Solutions for their performance of the PRESS review of our search strategy.

Funding

Internal Sources, Parker University.

Internal Sources, Palmer College of Chiropractic.

Contributions

Study conception was by B.C.C, R.B., S.M.R, S.A.S, and K.A.P.

Article review was performed by D.S.W and M.K., while S.A.S and K.A.P. served as article referees.

Data extraction, analysis, and synthesis was performed by D.S.W, M.K., S.A.S, and K.A.P.

The manuscript was written by D.S.W., while all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

A.G.G served as our research librarian, and contributed to manuscript preparation (search methodology).

Ethics declarations

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the World Health Organization, World Federation of Chiropractic, Chiropractic Association of Alberta, the United States Government, or the institutions with which the authors are employed.

Competing interests

The authors acknowledge the following competing interests: RB served in an independent contractor capacity for the World Federation of Chiropractic during this study, and received funding in this capacity.

BCC, SR, SAS, and KAP serve in a voluntary capacity for the World Federation of Chiropractic Research Committee and are members of the WFC Global Patient Safety Initiative Executive Committee.

SR, MF, and SAS are Editorial Board members of Chiropractic and Manual Therapies, and SR, BC, and SAS are Guest Editors for an article collection on patient safety published by Chiropractic and Manual Therapies. They had no involvement in the editorial review of this manuscript for the journal.

SAS reports research grant funding outside the submitted work from the U.S. National Institutes of Health—National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (paid to Palmer College of Chiropractic), travel support for research presentations from Parker Seminars, and voluntary membership on the Scientific Commission of The Clinical Compass.

KAP reports voluntary board member of the Chiropractic Future Research Workgroup; awardee of research grants unrelated to this work from chiropractic research funding bodies (Chiropractic Australia [including Chiropractic Australia Research Foundation], Australian Chiropractors Association, the Chiropractic Alumni [via the Macquarie University and Chiropractic Alumni Research Fund {MtCaRF}], the Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation, the American Chiropractic Association’s Council on Chiropractic Pediatrics, and the Royal College of Chiropractors).

MF reports research grant funding unrelated to this work from the Canadian Tri-Council New Frontiers in Research Fund, Chiropractic Australia [including Chiropractic Australia Research Foundation], Australian Chiropractors Association, the Chiropractic Alumni [via the Macquarie University and Chiropractic Alumni Research Fund {MtCaRF}], the Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation, Ontario Chiropractic Association, British Columbia Chiropractic Association, Chiropractor’s Association of Saskatchewan, RAND Research Pilot Grants, and the Danish Foundation for Chiropractic Research and Postgraduate Education.

KAP, SAS, MK, SR and RB report RAND Research Pilot Grant funding in the first quarter of 2025.

References:

Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021–2030

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021

Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS, editors.

To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System

Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2000. p. 287.The conceptual framework for the international classification

for patient safety [Internet].

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009

[cited 2024 Oct 10]. Available from:

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-PSP-2010.2Singer SJ, Gaba DM, Falwell A, Lin S, Hayes J, Baker L.

Patient safety climate in 92 US hospitals:

differences by work area and discipline.

Med Care. 2009;47(1):23–31.Nahin RL, Rhee A, Stussman B.

Use of complementary health approaches overall

and for pain management by US adults.

JAMA. 2024;331(7):613.Funabashi M, Pohlman KA, Mior S, O’Beirne M, Westaway M, De Carvalho D, et al.

SafetyNET Community-based patient safety initiatives:

development and application of a patient safety

and quality improvement survey.

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2018;62(3):130–42.Pohlman KA, Funabashi M, Ndetan H, Hogg-Johnson S, Bodnar P, Kawchuk G.

Assessing adverse events after chiropractic care at a chiropractic

teaching clinic: an active-surveillance pilot study.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2020;43(9):845–54.Thomas M, Swait G, Finch R.

Ten years of online incident reporting and learning using

CPiRLS: implications for improved patient safety.

Chiropr Man Ther. 2023;31(1):9.Patankar MS, editor.

Safety culture: building and sustaining a cultural change

in aviation and healthcare.

Ashgate: Aldershot; 2012. p. 243.Coleman BC, Rubinstein SM, Salsbury SA, Swain M, Brown R, Pohlman KA.

The world federation of chiropractic global patient safety task force:

a call to action.

Chiropr Man Ther. 2024;32(1):15.Arksey H, O’Malley L.

Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework.

Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK.

Scoping studies: advancing the methodology.

Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al.

PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR):

checklist and explanation.

Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.Patient safety culture research within the chiropractic profession:

a scoping review protocol [Internet].

Open science framework registry. [cited 2024 Oct 2].

Available from: https://osf.io/bcrkm/Swait G, Finch R.

What Are the Risks of Manual Treatment of the Spine?

A Scoping Review for Clinicians

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2017 (Dec 7); 25: 37MEDLINE (OVID) [Internet].

Ovid MEDLINE. [cited 2025 Feb 18]. Available from:

https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/ovid/ovid-medline-901Index to Chiropractic Literature [Internet].

Index to Chiropratic Literature. [cited 2025 Feb 18].

Available from: https://chiroindex.org/#resultsAllied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) [Internet].

EBSCO. [cited 2025 Feb 18]. Available from:

https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/

allied-and-complementary-medicine-database-amedCumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

[Internet]. EBSCO. [cited 2025 Feb 18]. Available from:

https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/

cinahl-databaseGoogle Scholar [Internet].

Google Scholar. [cited 2025 Feb 18]. Available from:

https://scholar.google.ca/McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C.

PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies:

2015 guideline statement.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.Medical Subject Headings [Internet].

National Library of Medicine. [cited 2025 Feb 18].

Available from: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/meshhome.htmlHirt J, Nordhausen T, Fuerst T, Ewald H, Appenzeller-Herzog C.

Guidance on terminology, application, and reporting of

citation searching: the TARCiS statement.

BMJ. 2024;9:e078384.Covidence systematic review software [Internet].

Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation;

Available from: www.covidence.orgWorld Federation of Chiropractic [Internet].

World Federation of Chiropractic Research Committee.

[cited 2025 Feb 18]. Available from:

https://www.wfc.org/research-committeeChiropractic Association of Alberta [Internet].

Chiropractic Association of Alberta.

[cited 2025 Feb 18]. Available from:

https://www.https://www.albertachiro.com/The Royal College of Chiropractors [Internet].

The Royal College of Chiropractors.

[cited 2025 Feb 18]. Available from:

https://rcc-uk.org/Pokras R, Iler L.

Bacterial load on the chiropractic adjusting table.

J Aust Chiropr Assoc. 1990;20:85–90.Terret A, Kleynhans A.

Complications from manipulation of the low back.

Chiropr J Aust. 1992;22:129–40.Jamison JR.

Informed consent: an Australian case study.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1998;21(5):348–55.Langworthy JM, le Fleming C.

Consent or submission?

The practice of consent within UK chiropractic.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(1):15–24.Bifero A, Prakash J, Bergin J.

The role of chiropractic adjusting tables as

reservoirs for microbial diseases.

Am J Infect Control. 2006;34(3):155–7.Smith M, Greene BR, Haas M, Allareddy V.

Intra-professional and inter-professional referral patterns of chiropractors.

Chiropr Osteopat. 2006;14(1):12.Thiel H, Bolton J.

The reporting of patient safety incidents—first experiences with the

chiropractic reporting and learning system (CRLS): a pilot study.

Clin Chiropr. 2006;9(3):139–49.Evans M, Breshears J.

Attitudes and behaviors of chiropractic college students on hand

sanitizing and treatment table disinfection:

results of initial survey and focus group.

J Am Chiropr Assoc. 2007;44(4):13–23.Evans MW, Breshears J, Campbell A, Husbands C, Rupert R.

Assessment and risk reduction of infectious pathogens

on chiropractic treatment tables.

Chiropr Osteopat. 2007;15(1):8.Langworthy JM, Cambron J.

Consent: its practices and implications in United Kingdom

and United States chiropractic practice.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(6):419–31.Rubin D.

Triage and case presentations in a chiropractic pediatric clinic.

J Chiropr Med. 2007;6(3):94–8.Rubinstein SM, Leboeuf-Yde C, Knol DL, De Koekkoek TE, Pfeifle CE.

The Benefits Outweigh the Risks for Patients Undergoing Chiropractic

Care for Neck Pain: A Prospective, Multicenter, Cohort Study

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007 (Jul); 30 (6): 408–418Vohra S, Johnston BC, Cramer K, Humphreys K.

Adverse Events Associated with Pediatric Spinal Manipulation:

A Systematic Review

Pediatrics. 2007 (Jan); 119 (1): e275–e283Evans MW, Campbell A, Husbands C, Breshears J, Ndetan H, Rupert R.

Cloth-covered chiropractic treatment tables as a

source of allergens and pathogenic microbes.

J Chiropr Med. 2008;7(1):34–8.Gunn SJ, Thiel HW, Bolton JE.

British chiropractic association members’ attitudes towards the

chiropractic reporting and learning system: a qualitative study.

Clin Chiropr. 2008;11(2):63–9.Miller JE, Benfield K.

Adverse Effects of Spinal Manipulative Therapy in Children

Younger Than 3 Years: A Retrospective Study

in a Chiropractic Teaching Clinic

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008 (Jul); 31 (6): 419–423Rubinstein SM, Leboeuf-Yde C, Knol DL, De Koekkoek TE.

Predictors of adverse events following chiropractic care

for patients with neck pain.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(2):94–103.Evans MW, Ramcharan M, Floyd R, Globe G, Ndetan H, Williams R, et al.

A proposed protocol for hand and table sanitizing

in chiropractic clinics and education institutions.

J Chiropr Med. 2009;8(1):38–47.Miller JE.

Safety of Chiropractic Manual Therapy for Children:

How Are We Doing?

J Clinical Chiropractic Pediatrics 2009 (Dec); 10 (2): 655–660Carlesso LC, Gross AR, Santaguida PL, Burnie S, Voth S, Sadi J.

Adverse events associated with the use of cervical manipulation

and mobilization for the treatment of neck pain in adults:

A systematic review.

Man Ther. 2010;15(5):434–44.Carnes D, Mullinger B, Underwood M.

Defining adverse events in manual therapies:

a modified Delphi consensus study.

Man Ther. 2010;15(1):2–6.Langworthy JM, Forrest L.

Withdrawal rates as a consequence of disclosure of risk

associated with manipulation of the cervical spine.

Chiropr Osteopat. 2010;18(1):27.Leach RA.

Patients With Symptoms and Signs of Stroke

Presenting to a Rural Chiropractic Practice

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010 (Jan); 33 (1): 62–69Smith M, Bero L, Carber L.

Could chiropractors screen for adverse drug events

in the community? Survey of US chiropractors.

Chiropr Osteopat. 2010;18(1):30.Carlesso LC, Cairney J, Dolovich L, Hoogenes J.

Defining adverse events in manual therapy: an exploratory

qualitative analysis of the patient perspective.

Man Ther. 2011;16(5):440–6.Gleberzon B.

A narrative review of the published chiropractic literature

regarding older patients from 2001–2010.

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2011;55(2):76–95.Turner LA, Singh K, Garritty C, Tsertsvadze A, et al.

An evaluation of the completeness of safety reporting in

reports of complementary and alternative medicine trials.

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11(1):67.Dagenais S, Brady O, Haldeman S.

Shared decision making through informed consent in

chiropractic management of low back pain.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(3):216–26.Sadr S, Pourkiani-Allah-Abad N, Stuber KJ.

The Treatment Experience of Patients

With Low Back Pain During Pregnancy

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2012 (Oct 9); 20 (1): 32Walker BF, Hebert JJ, Stomski NJ, Clarke BR, Bowden RS, et al.

Outcomes of Usual Chiropractic.

The OUCH Randomized Controlled Trial of Adverse Events

Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 (Sep 15); 38 (20): 1723–1729Wangler M, Peterson C, Zaugg B, Thiel H, Finch R.

How do chiropractors manage clinical risk?

A questionnaire study.

Chiropr Man Ther. 2013;21(1):18.Boucher P, Robidoux S.

Lumbar disc herniation and cauda equina syndrome following spinal

manipulative therapy: a review of six court decisions in Canada.

J Forensic Leg Med. 2014;22:159–69.Jevne J, Hartvigsen J, Christensen HW.

Compensation claims for chiropractic in Denmark and Norway 2004–2012.

Chiropr Man Ther. 2014;22(1):37.Pohlman KA, O’Beirne M, Thiel H, Cassidy JDavid, Mior S, et al.

Development and Validation of Providers’ and Patients’

Measurement Instruments to Evaluate Adverse Events

After Spinal Manipulation Therapy

Eur J Integr Med. 2014 (Aug); 6 (4): 451–466Hebert JJ, Stomski NJ, French SD, Rubinstein SM.

Serious Adverse Events and Spinal Manipulative Therapy of

the Low Back Region: A Systematic Review of Cases

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2015 (Nov); 38 (9): 677–691Marchand AM.

A Literature Review of Pediatric Spinal Manipulation and

Chiropractic Manipulative Therapy: Evaluation of

Consistent Use of Safety Terminology

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015 (Nov); 38 (9): 692–698Marchand AM.

A Proposed Model With Possible Implications for Safety and

Technique Adaptations for Chiropractic Spinal Manipulative

Therapy for Infants and Children

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2015 (Nov); 38 (9): 713–726Puentedura EJ, O’Grady WH.

Safety of thrust joint manipulation in the thoracic spine:

a systematic review.

J Man Manip Ther. 2015;23(3):154–61.Todd AJ, Carroll MT, Robinson A, Mitchell EKL.

Adverse Events Due to Chiropractic and Other Manual Therapies

for Infants and Children: A Review of the Literature

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015 (Nov); 38 (9): 699–712Winterbottom M, Boon H, Mior S, Facey M.

Informed consent for chiropractic care:

comparing patients’ perceptions to the legal perspective.

Man Ther. 2015;20(3):463–8.Gorrell LM, Engel RM, Brown B, Lystad RP.

The reporting of adverse events following spinal manipulation

in randomized clinical trials—a systematic review.

Spine J. 2016;16(9):1143–51.Innes SI, Leboeuf-Yde C, Walker BF.

Similarities and differences of graduate entry-level competencies

of chiropractic councils on education: a systematic review.

Chiropr Man Ther. 2016;24(1):1.Pohlman KA, Carroll L, Hartling L, Tsuyuki R, Vohra S.

Attitudes and Opinions of Doctors of Chiropractic

Specializing in Pediatric Care Toward Patient Safety:

A Cross-sectional Survey

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2016 (Sep); 39 (7): 487–493Pohlman KA, Carroll L, Hartling L, Tsuyuki RT, Vohra S.

Barriers to implementing a reporting and learning patient

safety system: pediatric chiropractic perspective.

J Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2016;21(2):105–9.Rozmovits L, Mior S, Boon H.

Exploring approaches to patient safety:

the case of spinal manipulation therapy.

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):164.Porcino A, Solomonian L, Zylich S, Gluvic B, Doucet C, Vohra S.

Pediatric training and practice of Canadian chiropractic

and naturopathic doctors: a 2004–2014 comparative study.

BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):512.Innes SI, Leboeuf-Yde C, Walker BF.

Chiropractic student choices in relation to indications,

non-indications and contra-indications of continued care.

Chiropr Man Therap. 2018;26(1):3.Zorzela L, Mior S, Boon H, Gross A, Yager J, Carter R, et al.

Tool to assess causality of direct and indirect adverse

events associated with therapeutic interventions.

Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(3):407–14.Salsbury SA, Vining RD, Hondras MA, Wallace RB, et al.

Interprofessional attitudes and interdisciplinary practices for older

adults with back pain among doctors of chiropractic:

a descriptive survey.

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019;42(4):295–305.Funabashi M, Pohlman KA, Goldsworthy R, Lee A, Tibbles A, Mior S, et al.

Beliefs, perceptions and practices of chiropractors and patients

about mitigation strategies for benign adverse events

after spinal manipulation therapy.

Chiropr Man Ther. 2020;28(1):46.Pohlman KA, Carroll L, Tsuyuki RT, Hartling L, Vohra S.

Comparison of active versus passive surveillance adverse event

reporting in a paediatric ambulatory chiropractic care setting:

a cluster randomised controlled trial.

BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9(4):e000972.Pohlman KA, Salsbury SA, Funabashi M, Holmes MM, Mior S.

Patient safety in chiropractic teaching programs:

a mixed methods study.

Chiropr Man Ther. 2020;28(1):50.To D, Tibbles A, Funabashi M.

Lessons learned from cases of rib fractures after manual therapy:

a case series to increase patient safety.

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2020;64(1):7–15.Alcantara J, Whetten A, Alcantara J.

Towards a safety culture in chiropractic: the use of the safety,

communication, operational reliability, and engagement

(SCORE) questionnaire.

Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2021;42:101266.Funabashi M, Holmes MM, Pohlman KA, Salsbury S, O’Beirne M, Vohra S, et al.

“Doing our best for patient safety”: an international and

interprofessional qualitative study with spinal manipulative

therapy providers in community-based settings.

Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2021;56:102470.Weis C, Stuber K, Murnaghan K.

Adverse Events From Spinal Manipulations in

the Pregnant and Postpartum Periods:

A Systematic Review and Update

J Can Chiropr Assoc 2021 (Apr); 65 (1): 32–49Funabashi M, Gorrell LM, Pohlman KA, Bergna A, Heneghan NR.

Definition and classification for adverse events following spinal

and peripheral joint manipulation and mobilization:

a scoping review.

PLoS ONE. 2022;17(7):e0270671.Stickler K, Kearns G.

Spinal manipulation and adverse event reporting in the pregnant

patient limits estimation of relative risk: a narrative review.

J Man Manip Ther. 2023;31(3):162–73.Dolbec A, Doucet C, Pohlman KA, Sobczak S, Pagé I.

Assessing adverse events associated with chiropractic care

in preschool pediatric population: a feasibility study.

Chiropr Man Ther. 2024;32(1):9.Pohlman KA, Funabashi M, O’Beirne M, Cassidy JD, Hill MD, Hurwitz EL, et al.

What’s the harm? Results of an active surveillance adverse event

reporting system for chiropractors and physiotherapists.

PLoS ONE. 2024;19(8):e0309069.Gorrell LM, Brown BT, Engel R, Lystad RP.

Reporting of Adverse Events Associated with Spinal

Manipulation in Randomised Clinical Trials:

An Updated Systematic Review

BMJ Open 2023 (May 4); 13 (5): e067526Junqueira DR, Zorzela L, Golder S, Loke Y, Gagnier JJ, Julious SA, et al.

CONSORT Harms 2022 statement, explanation, and elaboration:

updated guideline for the reporting of harms in randomised trials.

BMJ. 2023;24:e073725.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, for the CONSORT Group.

CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for

reporting parallel group randomised trials.

BMJ. 2010;340(1):c332.Vohra S, Kawchuk GN, Boon H, Caulfield T, Pohlman KA, O’Beirne M.

SafetyNET: an interdisciplinary research program to support

a safety culture for spinal manipulation therapy.

Eur J Integr Med. 2014;6(4):473–7.Murray J, Sorra J, Gale B, Mossburg S.

Ensuring patient and workforce safety culture in healthcare [Internet].

Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US);

2024. Available from: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/perspective/

ensuring-patient-and-workforce-safety-culture-healthcareO’Hara JK, Reynolds C, Moore S, Armitage G, Sheard L, Marsh C, et al.

What can patients tell us about the quality and safety of

hospital care? Findings from a UK multicentre survey study.

BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(9):673–82.Berger Z, Flickinger TE, Pfoh E, Martinez KA, Dy SM.

Promoting engagement by patients and families to reduce

adverse events in acute care settings: a systematic review.

BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):548–55.Hines S, Luna K, Lofthus J, Marquardt M, Stelmokas D.

Becoming a high reliability organization: operational advice for hospital leaders.

Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008.Myburgh C, Teglhus S, Engquist K, Vlachos E.

Chiropractors in interprofessional practice settings: a narrative

review exploring context, outcomes, barriers and facilitators

Chiropr Man Ther. 2022;30(1):56.Salsbury SA, Vining RD, Gosselin D, Goertz CM.

Be Good, Communicate, and Collaborate: A Qualitative Analysis

of Stakeholder Perspectives on Adding a Chiropractor

to the Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation Team

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2018 (Jun 22); 26: 29Graham SE, Coleman BC, Zhao X, Lisi AJ.

Evaluating rates of chiropractic use and utilization by patient sex

within the United States Veterans Health Administration:

a serial cross-sectional analysis.

Chiropr Man Ther. 2023;31(1):29.Bensel VA, Corcoran K, Lisi AJ.

Forecasting the use of chiropractic services within

the Veterans Health Administration.

PLoS ONE. 2025;20(1):e0316924.Lisi AJ, Salsbury SA, Twist EJ, Goertz CM.

Chiropractic Integration into Private Sector

Medical Facilities: A Multisite Qualitative Case Study.

J Altern Complement Med. 2018 (Aug); 24 (8): 792–800Ryan AT, Too LS, Bismark MM.

Complaints about chiropractors, osteopaths, and physiotherapists:

a retrospective cohort study of health, performance, and conduct concerns.

Chiropr Man Ther. 2018;26(1):12.Toth E, Lawson D, Nykoliation J.

Chiropractic complaints and disciplinary cases in Canada.

J Can Chiropr Assoc. 1998;42(4):229–42.Maiers MJ, Foshee WK, Henson DH.

Culturally sensitive chiropractic care of the transgender community:

a narrative review of the literature.

J Chiropr Humanit. 2017;24(1):24–30.Coulter ID, Singh BB, Riley D, Der-Martirosian C.

Interprofessional Referral Patterns

in an Integrated Medical System

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2005 (Mar); 28 (3): 170–174

Return to ALL ABOUT CHIROPRACTIC

Since 10-26-2025

| Home Page | Visit Our Sponsors | Become a Sponsor |

Please read our DISCLAIMER |